French Nuclear Testing at Mururoa

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) played a significant role in protest against French nuclear testing in the Pacific in 1973. The government requested the navy to send a frigate. It showed how much the government had changed its views from participation in the 1950s with Operation Grapple to outright opposition. It was most unusual for a government to send a naval ship in political protest. In fact, this was a unique act in New Zealand political history.

The French Tests

France sought to defend its strategic interests by developing an independent nuclear arsenal. The arsenal was named Force de frappe. It was France’s protection against the threat of Soviet invasion. However, France needed to test its nuclear bombs, and initial testing was conducted at the Reggane Firing Ground in the French colony of Algeria in February 1960.

An alternative became essential when Algeria was granted independence in 1962 and banned testing on the site.

New Pacific Test Site at Mururoa

In 1963, the French government decided to move its atmospheric testing programme to Mururoa Atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago. Testing was to begin in July 1966 and continue through to 1972 under the control of Direction des Centres d’Expérimentation Nucléaire (DIRCEN).[1]

A base for the testing administration and stores complex for ships and aircraft was set up at Hao Atoll, 270 miles (435 km) north-west of Mururoa.

New Zealand Appeals to International Court of Justice

The New Zealand Government first formally expressed its concern at France’s proposed testing programme in 1963 to the French Government. The process continued through diplomatic channels and inter-governmental meetings up to the end of 1973.

The main objection to the French testing programme was the hazard from fallout to the people of New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau Islands.[2]

New Zealand had monitored the testing and had recorded fallout over all these areas despite French attempts to mitigate the effects of the tests and the supposed ‘safer’ location. [3]

France declared a prohibited zone around Mururoa Atoll and Hao Island in 1965 but it also declared ‘danger zones’ during the tests themselves. These were not fixed and could be of any size and shape dependent on the test and French concerns. By 1972, the French Navy and Air Force operating from the test site were actively interfering with foreign shipping. [4]

Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s letter to the French Government in March of 1973 claimed that continued French atmospheric testing was a ‘violation of New Zealand’s rights under international law’ [5] and sought an assurance as to when the testing programme would end. France strongly contested the assertion. The New Zealand Government then advised that it would seek legal remedy under international statutes via the International Court of Justice.

By May 1973, New Zealand was convinced that French atmospheric testing was unlawful and sought other means parallel to the legal avenue of protest at the risks these tests posed.

Government sends Frigate

During the 1972 elections the Labour Party indicated that if elected it would send a frigate to Mururoa with a cabinet minister aboard, to further the protest against French atmospheric testing.

Between November 1972 and June 1973, naval staff worked on the operational plan for a frigate to sail to Mururoa to protest the next series of testing starting in July 1973. A frigate would need fuel. This meant that a supply vessel was needed, but the supply vessel HMNZS Endeavour was not able to carry the fuel oil that a frigate required.

The problem was solved with the help of Bob Hawke, then leader of the Australian Council of Trade Unions. [6] He successfully pressured the Australian Government to lend the tanker HMAS Supply as the support ship for the RNZN frigate.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force would airlift supplies to Rarotonga for uplifting and replenishment of any RNZN frigates at sea.

HMNZS Canterbury was the only RNZN frigate that could operate in a nuclear environment but would not be available until July 1973. In the end HMNZS Otago underwent a self-refit[7] and was sent. On board were Cabinet Minister Fraser Coleman and three representatives of the New Zealand media.

Peace Squadron

As in 1972, a fleet of private craft was sailing to Mururoa. This Peace Squadron was very disappointed that HMNZS Otago would not act as a mothership for them. The New Zealand Government was concerned that the French would ask Otago to remove the protest craft from the prohibited zone, which would result in negative publicity.

On 22 June 1973, the International Court of Justice supported New Zealand’s application for interim measures to halt the nuclear tests but the dates for exchanges of memoranda between France and New Zealand were set well after the completion of the testing programme.

France proceeded with the 1973 plans.

Active Operations by the RNZN

The first vessel deployed by the RNZN was HMNZS Lachlan. She conducted signal intelligence gathering and spent the period from 21 June to 1 July 1973 steaming off Rarotonga. Lachlan tracked communications under the direction of Lieutenant-Commander Dennis Milton. Milton had embarked especially for this purpose, having been involved in communication intercepts since 1944.

The commanding officer, Commander Ian Munro, calculated the bearing from Waiouru to Mururoa Atoll for HMNZS Irirangi, so that the directional aerials could be directed to listen in to the French communications.

Lachlan refuelled at sea from the Royal Air Force tanker Tideflow. However, the British made it very clear to the New Zealand Government and the RNZN that they were not supporting the New Zealand protest action.[8]

On 2 July 1973, HMNZS Lachlan received orders to return to New Zealand. A course had been set to avoid HMNZS Otago so that Lachlan’s part in obtaining signal intelligence was kept from the media contingent aboard Otago.

HMNZS Otago sent to Mururoa

Prior to departure, the ship’s company was offered the chance to opt out of sailing with the Otago. Twenty-two took up the offer, 10 for personal reasons and 12 for family reasons. No officers or specialist tradesmen opted out.

When on deployment to Mururoa, Otago would be under the direct control of Rear Admiral E. C. Thorne, CB, CBE, Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), who in turn reported directly to Lieutenant-General Richard Webb, Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), [9] who took his direction from the Kirk government.

There were three parts to the orders:

- Rules of Engagement (ROE) – the written authority to fire upon French vessels in self-defence if the need arose. Otago had orders to fuse its shells [10] for the voyage to the exclusion zone.

- The action to be taken if the Otago was severely contaminated by fallout and the procedure for seeking medical assistance from the French

- Details of a secret communications safety circuit with the French authorities to avoid a direct hazard to the New Zealand frigate.

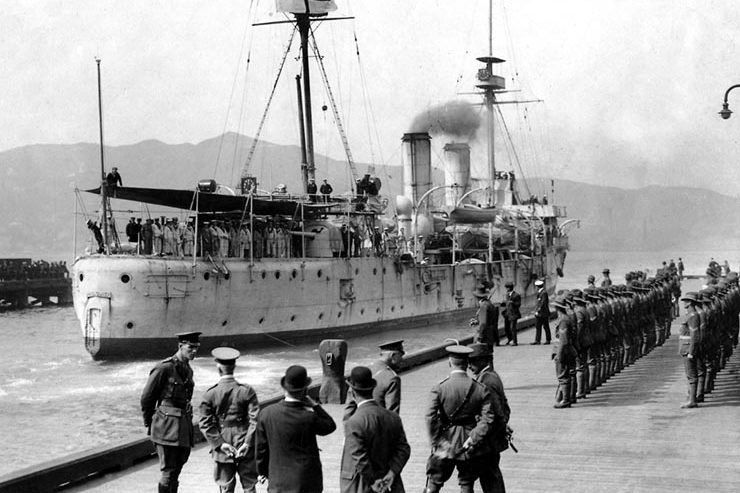

Minister for Immigration and Mines Fraser Colman was selected as the cabinet minister to sail with Otago. At a dockside press conference timed for Otago’s departure on the 28 June, Prime Minister Norman Kirk stated that ‘this is a mission of purpose’, and that the voyage of Otago would ‘ensure that the eyes of the world are riveted on Mururoa’.

On 4 July, Otago received orders to pass into the French-declared ‘Intermediate Zone’ with instructions to contact by Morse code twice daily an unidentified radio station. It was discovered later that this was the safety link to the French authorities.

When France stated that it would proceed with its tests despite the presence of Otago, Norman Kirk assured them that the frigate would not enter French territorial waters but rather what the French called their ‘danger zone’.

A French P2 Neptune maritime patrol aircraft made several passes over the Otago on 6 July, but there was no communication. France then advised it was activating the test zone equal to 72 miles (116 km) around the test site, the area that Otago would be entering.

Two days later a French Dunkerque-class minesweeper appeared 3 miles (5 km) off the stern of Otago. It shadowed the ship until contact was broken when Otago changed course.

Otago would sail into the zone until 23 July, maintaining a course to avoid territorial waters but sailing in and out of the zone to rendezvous with Supply in order to replenish fuel and provisions. French surveillance continually photographed the Otago until about 14 July.

On 17 July two French frigates boarded the protest yacht Fri and took it under tow to Hao Atoll. Otago made preparations in case the French sought to close with them also. Orders were received from Wellington on Thursday 19 July to proceed closer to Mururoa Atoll as a test was about to occur.

International Intelligence Gathering

All the major nuclear powers had naval forces acting as observers of the test including: RFA Sir Percivale, USSR Research vessels Akademik Shirshov and Volna, and others. Only the RNZN was acting in a protest role.

Approaching the territorial limits, Otago could see a balloon with the device slung beneath it. Personnel were told to prepare for a test the next day. At 0800 local time, the French detonated a device above the atoll at 2000 feet (610 m). Otago was 21.5 miles (35 km) west of the detonation.

HMNZS Canterbury arrives to Crowded Seas

Canterbury left Auckland to replace Otago on 14 July, equipped with the RNZN’s first onboard computer nick-named ‘Clarence’ . Clarence would monitor the yield of the French bomb and fallout.

Despite being hampered by contamination in the port boiler, Canterbury rendezvoused with Otago on 22 July. Otago was ordered back to Mururoa to observe what was thought to be the second test.

While Canterbury fixed some engineering issues, Otago remained on duty and moved to a new location for observation.

Otago transferred equipment, personnel and Fraser Colman to the Canterbury. Canterbury was then subject to the same level of inspection that Otago had experienced from French surveillance planes.

After a delay noted by the Canterbury from the radio traffic on the morning of 28 July,[11] a device was detonated at 1032 feet (315 m).

Aftermath

The French Government announced in 1975 that they would end atmospheric testing and move to underground testing at Mururoa.

This remained the case until June 1995 when France recommenced testing at Mururoa, finally ending in January 1996. France then signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and to date has not conducted any further testing.

Mururoa is still French territory and is treated as a secure site but the facilities have been dismantled and decommissioned.

Bibliography:

[1] French Nuclear Testing in the Pacific: International Court of Justice Nuclear Tests Case New Zealand v. France, Wellington: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, July 1973, p. 9.

[2] ibid., pp. 9-10.

[3] ibid., p. 11.

[4] ibid., p.11.

[5] ibid, p. 10.

[6] ACTU: Australian Council of Trade Unions

[7] Self-refit: Prior to WW2 whenever a ship was in for any type of work by the dockyard it was known as a refit. In theory, the vessel under self-refit should be able to make steam within 48 hours.

[8] Gerry Wright, ’30 Years Ago: The Navy at Mururoa’, The Raggie 17:3 (2003), p.6.

[9] The Navy List, Wellington: Ministry of Defence, 29 February 1973, p. 6.

[10] Fused shells: Loaded shells travelled ‘unfused’ for safety. When going into action fuses were inserted making them ‘live’.

[11] This was the 32nd test since 1966.