Greenpeace had been very active in the peace flotilla at Mururoa in 1973. This article summarises Grant Apperley’s official report on the role the Royal New Zealand Navy had in salvaging the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior and in preserving evidence for the police investigation.

It is reprinted from Navy Today July 2005, when it was written to mark the 20th Anniversary of the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior.

This article also appeared in The White Ensign Issue 05 Winter 2008.

The sinking

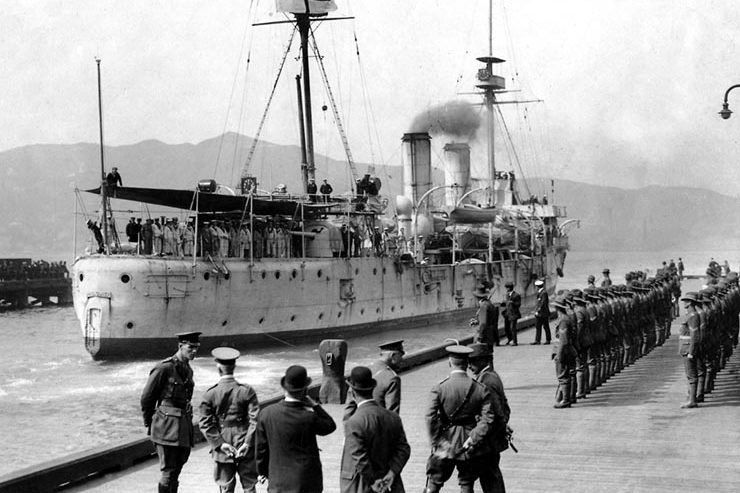

On Thursday 10 July 1985, the British-registered Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior was sunk in Auckland Harbour by French saboteurs of the DGSE (Directorate-General for External Security).

Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira was killed when limpet mines attached to the ship exploded.

The navy’s initial response was just two hours after the explosions, when Leading Diver (LDR) Schmidt of the Operational Diving Team (ODT) entered the wreck and discovered Pereira’s body. The Dive Team also conducted a search of the hull and wharf for any other explosives. None were found.

The police declared the wreck a crime scene. They wanted it recovered for forensic examination. They also wanted to examine the seabed under the ship.

Beginning the following Monday, the ODT, under the command of Lieutenant Hugh Aitken, conducted a survey of the wreck. They reported a huge hole in the engine room and extensive damage around the propeller and propeller shaft. In the subsequent two weeks, the naval dockyard team assessed various options for salvage. The divers began clearing the interior of the ship, moving some 30 tons (27.2 tonnes) of equipment and fittings out of the wreck.

The Salvage

The salvage task was a daunting one. Rainbow Warrior had sunk onto her starboard side, burying the huge (2.4 x 1.5 m) hole in the hull in the soft mud of the seabed. The impact of the two limpet mines was immense. Shock blast and shrapnel damage had spread far into the ship.

When the Rainbow Warrior was eventually salvaged, a full inspection revealed that the ship could never be made seaworthy again.

Many preparations went on in the next two weeks, before the Master of the Rainbow Warrior signed a salvage agreement with the police on 24 July. The next day, Commodore Tempero (Commodore Auckland) signed an Administration Order placing Gavin Apperley, Constructive Manager at HMNZ Dockyard, in charge of the salvage. The navy’s resources, including the ODT, were placed in support of Apperley’s team. The Ministry of Transport’s Oil Pollution Unit was also available, led by Gerry Wright, a former naval officer.

Lieutenant Commander Brian Ward, then Assistant Queen’s Harbour Master and in charge of the Support Team of Philomel sailors, saw the salvage in three main phases.

PHASE ONE | 19–28 July

The removal of all accessible items

A thorough survey of damage

Commence patching of stern damage.

PHASE TWO | 28 July–19 August

Patching – Engine room patches placed

Test plumbing

Attach air bags.

PHASE THREE | 19–22 August

Raising ship

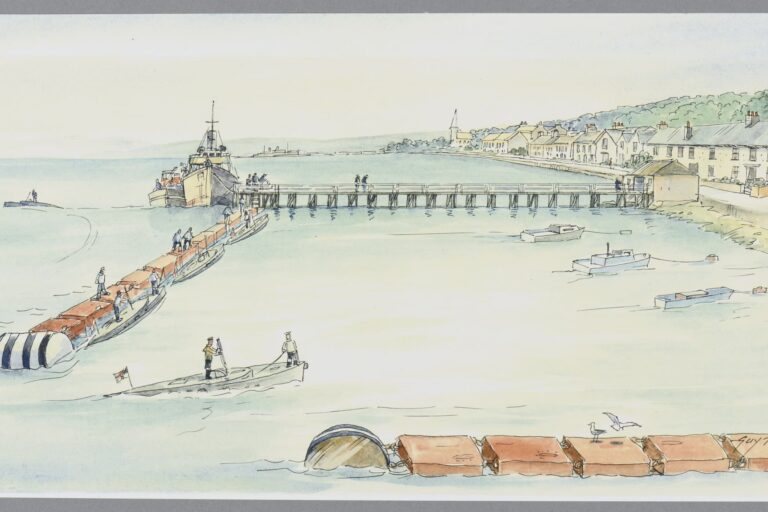

Moving ship south along Marsden Wharf

Finally moving ship to Calliope Dock.

Even though the trawler had been sunk in shallow water and next to a wharf, the salvage was not simple. First there were the structural limitations of the wharf itself. Then there were the structural limitations of the ship.

Rainbow Warrior was old and suffered corrosion in key decks and bulkheads. The way that the ship had been converted also meant that few of her internal bulkheads were in fact watertight (because cable runs and other alterations had been made without regard for basic ship fitting).

The salvage effort began with the divers. They had to clear the interior, black shrapnel holes and cable runs, and guide the suction hoses to rid the hull of the mud. Even the ship’s drawings had to be recovered from underwater and all this had to be done with police evidence in mind. It was winter; the days were short, the water was cold and polluted with diesel from the bomb-damaged fuel tanks, and the wind would blow up a nasty chop that pounded into the basin beside Marsden Wharf.

After several approaches it became inevitable that the dockyard would have to fabricate a patch to cover the main hole in the engine room, and the divers would have to attach it to the hole. However, because the ship could not be moved, the patch would have to be applied with the ship still on her side with barely a foot of clearance for the divers to operate in.

Underlying each of the decisions were many hours of calculations by the constructor and his team. For all its size and apparent strength, a ship is a dynamic object, and when filled with 1000 tons (907 tonnes) of water and weakened by shock or blast the structure can easily buckle or collapse. The dockyard team knew that a wrong move could break up the ship, or worse an error could cause casualties among the salvage team. The dockyard staff were assisted by the Ministry of Transport, who made their Apple III computer (in Wellington) available to assist with calculations.

For the divers it was continuous hard work. Lieutenant Aitken reported that, ‘The salvage was a challenging task, conducted in conditions of nil visibility and often involving a high degree of difficulty.’

The divers used surface supply breathing apparatus (SSBA), which meant they had a continuous air supply. In the relatively shallow depths, they didn’t have to worry about decompression tables, and the SSBA meant they enjoyed hard-wired communications with the surface.

They quickly developed an excellent working relationship with the police, Auckland Harbour Board and the fire brigade (who provided additional pumps to assist the salvage).

Early on the decision was made to hire salvage airbags from Salvage Pacific Ltd in Fiji. These bags, each with a 5-ton (4.5-tonne) lift capacity were mounted along Rainbow Warrior’s starboard side to give additional buoyancy and to control the lift. That meant more work for the Operational Diving Team, who had to bolt and weld on the steel eyepieces to fasten each airbag to the hull of the ship.

In addition, the Ministry of Transport loaned Captain G. C. Wright to assist and oversee the large capacity Ministry of Transport pumps. ‘Always helpful, always cheerful, Captain Wright became a strong member of our team,’ Lieutenant Commander Ward reported.

Lieutenant Commander Ward’s support team did all the surface tasks imaginable: working on and in the Rainbow Warrior to make the accessible structure watertight, operating the pumps, even cooking for the whole salvage team. Few across the harbour in Philomel understood the difficult conditions in which they were working. For example, the supply of dry socks became a bone of contention when the Supply Depot, not understanding the nature of salvage work, told the salvage crew to wash and dry their own socks.

In mid-August, as more of the ship was being pumped out and made watertight, it became clear that the navy’s Rover gas turbine pumps were not up to the task. The fire brigade supplemented the pumping effort at short notice, in time for the final lift. When the final lift took place, there was a cacophony of diesel engines: the five big Ministry of Transport salvage pumps, five more from the Harbour Board and even the scream from the two Rovers, not to mention the roar of air compressors supplying the divers and filling the salvage airbags.

It was at 0245 on 21 August that the final lift began. By dawn, Rainbow Warrior was partially afloat and almost upright. She was moved south, and the pumps were rearranged for the harbour crossing. At 1245 on 22 August, Rainbow Warrior was docked in Calliope Dock. As water drained down, the full extent of the bomb blast could be seen.

A Royal Navy underwater explosives expert flew in to assist with the police examination; finally the Dockyard was tasked with sealing the ship and making her watertight for eventual disposal. On 25 September the Rainbow Warrior was undocked and the Navy’s part in her salvage came to an end.

Today the Rainbow Warrior lies in Matauri Bay, Northland, and is accessible to sports divers. Her salvage was an interdepartmental and commercial team effort led by the Naval Dockyard and involving many from HMNZS PhIlomel.

The salvage of the Rainbow Warrior is an event the New Zealand Navy can look back on with pride.

References:

G.C. Apperley, Salvage of the Rainbow Warrior: July/August 1985 at Marsden Wharf East, Report from Constructive Manager, HMNZ Dockyard, Auckland: RNZN, 1985.