Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, wrote a paper for cabinet on Saturday 20 March 1909, proposing that New Zealand offer to meet the cost of one and if necessary two, first class battleships for the Royal Navy. HMS New Zealand was laid down on 20 June 1910 as a unit of the indefatigable class.

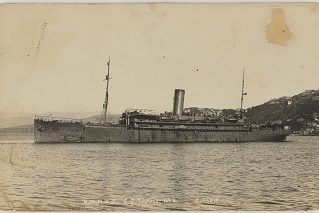

The 1st of July 1911 was a gala day at Fairfield’s Shipyard in Glasgow, when Teresa, Lady Ward, wife of the Prime Minister of New Zealand broke the traditional bottle of champagne on the bow of a new battlecruiser and declared ‘I name this ship New Zealand and God bless all who sail in her.’ She then took a silver mounted axe, with an ivory handle and cut the last wire holding the ship on the slipway. With a tremendous roar the battlecruiser slid down into the cold waters of the Clyde.

After the ceremony the Chairman of Fairfield’s presented the axe, contained within its own silver casket, to Lady Ward. The outside of the box is engraved with Scottish and New Zealand scenes and an inscription outlines the background to the axe:

Presented to Lady Ward by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company Limited on the occasion of the launch of the armoured cruiser New Zealand on 1 July 1911

How did this event come about and what was New Zealand’s involvement?

With the launching of HMS Dreadnought in 1906, the Royal Navy ushered in a new standard for fleet capability, which it has often been said, made all other battleships obsolete. For centuries the central tenet of Royal Navy policy had been the ‘two power standard.’ This was a simple measurement of numbers, whereby the Royal Navy was to have at least the same number of battleships as the next two largest navies combined. The launch of Dreadnought laid the existing margin aside.

A further development of the key features of Dreadnought, by Britain’s First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, extended to a new type of large armoured cruiser that was to become the battlecruiser. The first of this new type was launched in 1907. Of such magnitude were the advances in technology incorporated in these two ships, that capital ships were thereafter designated “Dreadnoughts” or “Pre-Dreadnoughts”.

The advent of these vessels sharply increased the cost of capital ships, added to which was the need to out-build all other navies. These developments coincided with a change in Government as a result of the 1905 elections, the new Government being determined to reduce expenditure on defence overall, and the Navy in particular. Important from a naval perspective was a gradual revision of the two-power standard, to a navy with 1.5 times the number of capital ships than possessed by its nearest rival, which by this time was Germany. In May 1908, the Government had agreed to a building programme of four dreadnoughts and if necessary six, to be laid down 1909. By July, however, intelligence was indicating that the German building programme was more advanced than anticipated and Fisher informed McKenna that a crisis was looming and that six ships needed to be built.

The crisis that Fisher had foretold was fully developed by the end of 1908, or at least one was perceived. Germany had laid down its first four dreadnoughts in August 1907 and by 1909 it was projected that it would have 13 to Britain’s 18, which did not nearly meet the two power standard. In response the Admiralty revised its requirements; seeking the construction of a further two ships in January 1909, for a total of eight ships.

The ‘dreadnought crisis’, resulted in a particularly acrimonious debate within the British Government. On one side were those supporting the Navy and on the other those seeking to minimise expenditure on naval defence. The debate was not confined to the United Kingdom. In New Zealand it was closely followed with regular reports in the major newspapers, and even details of the German shipbuilding programme were published. In Australia, too, the naval crisis was a matter of concern. The Sydney Daily Telegraph went so far as to suggest that Canada and Australia should each offer to meet the cost of a dreadnought, ‘showing that these comparatively rich young dominions would be quick to reinforce the Motherland for any emergency.’

Against this background the Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, wrote a paper for cabinet on Saturday 20 March 1909, proposing that New Zealand offer to meet the cost of one and if necessary two, first class battleships for the Royal Navy. He convened cabinet the following day and on Monday 22 March telegraphed the Governor, then engaged in a tour of the country, inviting him to forward the offer to the British Government. The Governor immediately did so, expressing his pride and satisfaction at the offer. On 24 March the Secretary of State for the Colonies telegraphed the acceptance of the offer, and the gratitude of the King.

Sir Joseph’s offer was subsequently approved by Parliament, but not without some dissension in the House. This was not because of the offer itself, which was generally agreed, but because the Prime Minister had not sought the approval of Parliament in the first instance.

Whether or not the offer of a battleship was a considered decision on the part of the Prime Minister; or an impulsive reaction to the suggestion that Australia might fund one, it is not really known. Certainly the Prime Minister stated in the press that his was not an impulsive decision. Similarly, New Zealand’s offer was intended to supplement the Royal Navy’s building programme, not to simply relieve the burden on the British taxpayer, as subsequently transpired. In any event, it was perhaps no co-incidence that Sir Joseph Ward was created a Baronet on the Coronation of King George V on 22 June 1911.

New Zealand’s offer having been accepted, it was another year before the contract was let for building the ship, which, instead of a battleship, was a battlecruiser. In the interim too, Australia had decided to build a navy, based on a battlecruiser, so that construction of the two ships went to tender at the same time. Two tenders were received, one from John Brown and Company and the other from Fairfield Shipbuilding. The tender of John Browns was higher, but for reasons not known, the Australians agreed to accept that tender, leaving the Fairfield’s tender for New Zealand. The contract for construction was between the firm and the Admiralty, but with New Zealand paying the bills. Admiralty stores were supplied at “Rate Book” price, plus 20 percent.

Once the building of the ship commenced there was some discussion over the name to be given to it, with Zealandia, being the New Zealand Government’s choice, probably because a pre-dreadnought battleship had been commissioned as HMS New Zealand in 1905. With Australia deciding to name their ship Australia, the Admiralty suggested that New Zealand would be preferable for the Dominion’s ship and offered to rename the existing HMS New Zealand, which was accepted. After considerable discussion of various names for the existing ship, it was renamed Zealandia, in November 1911.

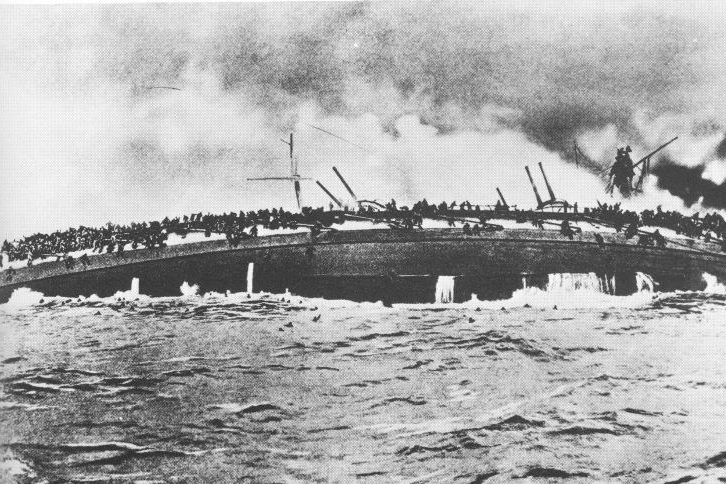

HMS New Zealand was laid down on 20 June 1910 as a unit of the indefatigable class, as was HMAS Australia. Together with the name ship of the class, they were an improved version of the first class of battlecruisers, the Invincible class. For reasons not satisfactorily explained to date, this class was inferior in all respects, particularly speed and armour protection, to the first German battlecruisers, SMS von der Tann and the Moltke class, and also to the second group of British battlecruisers, the Lion class, of which the name ship was laid down in September 1909. It is notable that the 11 inch German guns were comparable to the 12 inch of the British. A comparison of these classes of ship is shown in table I

Table 1

| Class | Laid Down | Displacement | Length | Main Armament | Speed | Armour (% of displacement) |

| Invincible | 1906 | 17,527 | 173m | 8 x 12inch | 26 knots | 20.1 |

| Indefatigable | 1909-10 | 19,051 | 180m | 8 x 12 inch | 26 knots | 19.9 |

| Von deer Tann | 1908 | 19,370 | 172m | 8 x 11inch | 27 knots | 29.8 |

| Moltke | 1908-09 | 22,979 | 187m | 10 x 11inch | 28 knots | unknown |

| Lion | 1909-10 | 27,149 | 213m | 8 x 13.5inch | 28 knots | 24.2 |

During construction there were developments in the technology of armour plating, which resulted in some delays in manufacture. Coupled with the pace of warship construction, this caused a little delay in completion of New Zealand although the government was surely pleased to learn that Messers Fairfield did not pass on any cost associated with this delay.

The ship was completed in November 1912 and commissioned by Captain Lionel Halsey at Glasgow, on 19 November. On 5 February His Majesty King George V visited the ship to bid “bon voyage” and the following day New Zealand embarked on a world cruise, showing the flag throughout the Empire. While the main reason for this cruise was undoubtedly to show the ship to the New Zealanders whose gift it was, it is apparent from the press reports that an ulterior motive was to encourage South Africa and Canada to make similar gifts.