Prelude to Second World War

The Walrus

In 1936, one of two aircraft designed by the brilliant British aircraft designer RJ. Mitchell was in production at Supermarine Aviation Works in Southampton, the other was about to be built as a prototype.

Both were to serve throughout the Second World War, with strong New Zealand connections. The prototype was the Supermarine Spitfire, arguably the most famous fighter of the war.

The aircraft in production was the Walrus, which was almost unknown during the war, but in Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm (FAA) and Commonwealth Air Forces’ service, was to provide a valuable contribution to the war effort.

Outwardly the two aircraft had no obvious family connection.

The Spitfire, an advanced design monoplane with graceful curves, distinctive Merlin engine, and top speed of over 340 mph (547km/hr), contrasted dramatically with the Walrus’s antiquated‑looking biplane design, shoe‑box fuselage and noisy radial engine driving a four‑bladed wooden pusher propeller, with top speed, on a good day, of 135 mph (217km/hr).

The type impressed the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm enough for the RAF to place an order on the FAA’s behalf for 12 aircraft in 1935.

The name Walrus was adopted for the new aircraft. As Spitfire production accelerated, Walrus production was shifted to Saunders Roe Ltd, on the Isle of Wight.

When introduced into FAA service in the late 1930s the ungainly‑looking Walrus reminded sailors of an old shaggy bull walrus, and it was nicknamed ‘Shagbats’. Another salty name for the Walrus was ‘Pusser’s Duck’.

The Walrus was designed for carriage on most capital ships and cruisers of the day for reconnaissance, spotting fall of shells from the ship’s guns, as an anti‑submarine patrol ahead of the parent ship, and as a communications aircraft to and from the ship.

In its roomy hull were seats for three crew ‑ pilot, observer and telegraphist/air‑gunner (TAG) ‑ and, if required, one or two passengers.

The Walrus was not without teeth, as it could carry a Lewis machine‑gun in the forward hatch and another in the rear hatch.

Some of the New Zealand Walruses, for example L2241, carried Vickers X’ guns, bombs or depth charges on a combination of universal and light series‑bomb carriers could be loaded under the lower mainplane, not exceeding a total of 760 lb (345kg).

The Walrus, with its mainplanes folded, was carried on a special catapult structure on the upper deck, where maintenance was a challenge to the servicing crew, given the pitch and roll of the ship.

The rugged construction of the Walrus allowed it to be launched from the ship, a procedure started with the ship’s Tannoy announcing, ‘Catapult crew report at the double ‑ man the aircraft.’

The steel box‑girder catapult was positioned to abeam ship, its telescopic ramp extended, and the aircraft manned, with its wings spread and locked and engine started.

Hand‑starting was a challenge:

It took a strong rating to turn the starting handle standing on the lower rnainplane … the angle of mainplane incidence, the slope of the wing made it hard. For safety a cord was lashed onto the handle in case, as the engine fired up, the starting dogs did not push the handle out and when trying to retrieve it, the handle was dropped, which may have resulted in it going into the prop. A water start was even dicier, with the aircraft bobbing up and down on the waves.

When going full blast, the flames leaping out of the aircraft’s exhaust system ‑ a series of short pipes on a collector ring ‑ looked like a stove gas‑ring, especially at night, thereby earning the aircraft another nickname, ‘the flying gas‑ring’.

With the engine running, the Walrus on its cradle was moved to the rear of the catapult onto the launch position.

When the engine reached full revs, deafening the launch crew, the catapult officer waved a green flag round his head, and, acknowledged by the pilot’s ‘thumbs‑up’, fired the catapult cordite charge, hurling the aircraft down the catapult and into the air, where it staggered away at 80mph.

Recovering the aircraft at sea was also exciting. As the aircraft approached the ship the TAG flashed the ‘Ready to land’ signal with his Aldis lamp and the ship hoisted the landing Rag.

With the Tannoy call ‘Prepare to recover aircraft’, the ship steamed into wind, then commenced a hard turn, creating a smooth slick onto which the pilot landed the Walrus.

With the ship ideally moving slowly ahead, the pilot taxied the Walrus close to the lee‑side and, if the ‘direct recovery technique’ was used; the TAG would climb onto the centre section and attach his safety harness to avoid sliding off the wing or into the spinning propeller. He would then secure the lifting slings as the pilot taxied to a position underneath the ship’s crane.

If the ship was at anchor and had rigged a boom over the side, the aircraft would taxi up to it and the observer would secure the aircraft to the boom with a strop.

To prevent damage to the aircraft, long bamboo poles fitted with soft pads at one end were wielded by the ship’s crew to fend off the Walrus’s wings from the ship’s side.

The ship’s crane operator’s timing had to be exact to enable the hook to be hoisted or lowered very quickly to ensure the propeller was not fouled if the pilot overshot or, once hooked, to take the strain as the aircraft rose or fell in the seaway.

Once the hook mechanism was secured, the crewman gave the ready signal, the deck officer confirmed the hook was engaged and signalled the pilot to cut the engine.

Then, judging the ship’s roll and the sea swell, the crane operator timed his lift to raise the Walrus high over the side onto the cradle. Two lines were thrown to the pilot and observer, who secured them to the wing‑tip, steadying wires clipped along each lower mainplane, while a third could be secured to the after hatch if the weather was very rough.

Launching and recovery were also tricky operations, sometimes resulting in damage or loss of aircraft. If the ship was in danger of enemy attack during the recovery action, the speed was accelerated, with the parent ship moving forward at 15 knots, thereby increasing the chances of an accident.

HMS Achilles and the Walrus

The first Walrus with a New Zealand connection was a Mk 1 (RAF serial number K5774), the third production Walrus to be built, and unique as the first Walrus allocated to the FAA.

HMS Achilles, of the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, received this Walrus in April 1936, shortly before sailing to New Zealand, the first to carry a Walrus as its resident aircraft.

Lieutenant T.P Coode RN was appointed pilot, with Lieutenant J.E. Smallwood RN as observer.

As Achilles could carry only one aircraft on its catapult system, the ship’s reserve Walrus, K5783, was shipped separately to Auckland and assembled at Hobsonville in May/June 1937.

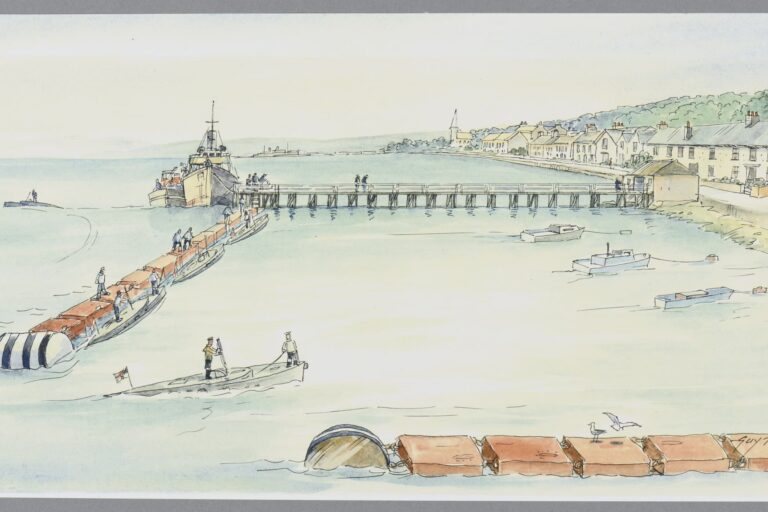

Shortly before Achilles entered Auckland Harbour on 6 September 1936, the Walrus was catapulted from the ship to fly to Hobsonville to await further duties. On board to support the Walrus operations, were two New Zealanders serving in the RN, TAG Peter Trent and parachute packer Cliff Gubb, plus two RAF technical personnel, a corporal air gunner and a leading aircraftsman fitter.

When Achilles was berthed at Devonport, naval personnel assigned to duties with the Walrus were detached to RNZAF Hobsonville.

Hobsonville also became the designated maintenance and storage depot for Walrus engines, airframes and major spares. The smaller spares were retained at the Naval Base at Devonport.

The Walrus rejoined Achilles for its first southern cruise in early November 1936, visiting Hastings, Wellington, and Lyttelton, sailing around the South Island and up the West Coast to New Plymouth, and returning to Auckland on 3 December, for Christmas. The Walrus was flown to Hobsonville.

In early January 1937, Achilles and the Walrus went for a summer cruise down the East Coast to Wellington, then to the Marlborough Sounds, and during March and April there were exercises with ships of the Royal Australian Navy.

In May, the Commanding Officer of Achilles, Captain I.G. Glennie RN, questioned the usefulness of the Walrus in a report to the Commodore Commanding the New Zealand Station, pointing out that:

during the 250 days subsequent to 4 April 1936, during which the Walrus Mk1 was borne, the machine was out of action for 93 days, 38 of which were absorbed by routine inspections, and no less than 55 by modifications and alterations’

Glennie’s report also analysed the ability of the Walrus in open seas in the Pacific, particularly along the trade routes cruisers were required to monitor, where heavy seas often precluded the aircraft from being recovered in waters not protected by nearby land:

It appears inevitable that strategic freedom must be surrendered if successful, and even moderately prolonged, aerial reconnaissance is required. Upon the open sea the utility of the aircraft must remain an entirely unknown quantity. It might be lost within the first few hours, it might render yeoman service within the same space of time or it might be held up by weather conditions for weeks on end.

The report concluded that,

while the Walrus was a most useful machine, the provision of suitable land aerodromes in strategic locations from which long‑range land‑based aeroplanes could operate, is the better solution to protection of our trade routes.

The report was passed to the Air Board for comment.

In reply, the Air Secretary T.A. Barrow, noted the limitations of the Walrus and pointed out that the new ‘Wellington’ aircraft ordered for the two New Zealand squadrons could allow long‑ and wide‑range reconnaissance in the Southern Pacific, though it would not always match the reconnaissance capability of a cruiser borne aircraft.

As history shows, the Wellingtons did not reach New Zealand; they were handed to the RAF at the outbreak of the Second World War.

The lack of a long‑range land‑ based reconnaissance aircraft during the early stages of the war placed New Zealand’s trade routes in considerable jeopardy.

Until the arrival of the RNZAF’s Catalina flying boats in 1943, reconnaissance of these routes was undertaken by civilian flying boats based in New Zealand and Australia, obsolete Singapore III flying boats at Fiji and occasional flights by the cruiser‑borne Walruses.

HMS Leander and the Walrus

When HMS Leander, the second cruiser for the New Zealand Division, was commissioned in April 1937, its two Osprey naval fighter aircraft were traded for Walrus K8541.

Leander sailed from the UK on 2 July and 67 days later arrived in Auckland. Looking after Leanders Walrus were Lieutenant Commander B. Logan RN, observer, and Flight Commander Lieutenant G.WR. Nicholl RN, pilot, and Leading Telegraphist H. Windleborn, TAG, a New Zealander.

On the way to New Zealand, Leander called at several South Pacific islands to claim them for Britain, the Walrus usually being launched to carry out aerial photographic surveys.

Pitcairn was one of the islands visited, Leander being the first warship there since 1913, and the ship’s company was well hosted by the islanders.

Another Walrus, L2222, joined the fleet after assembly and air testing at Hobsonville in June 1938, and remained at Hobsonville as the immediate reserve for Leander. All Walrus aircraft were operated by No. 720 Catapult Flight.

During 1937 and 1938, the two New Zealand cruisers and their Walruses were involved in the race between the British and Americans to establish flying‑boat alighting bases in the Pacific.

In the mid 1930s, Imperial Airways of the UK and Pan American of the US both realised the potential of civil flying‑boat air services across the Pacific Ocean and began surveys with a view to claiming the best locations for their services.

On 24 November 1937, while Achilles and Leander were in Wellington, the first Walrus accident occurred.

K8541 from Leander was being flown by Lieutenant G.WR. Nicholl, with Corporal Ison and Leading Aircraftsman Simcox as crew, when the pilot inadvertently landed the aircraft on the harbour with the wheels extended.

The undercarriage warning horn would have alerted the pilot to the fact that his wheels were down as he throttled back for landing, but it was switched off!

On contact with the sea, the aircraft immediately nosedived underwater. The crew was quickly recovered but the Walrus was a write‑off. It was replaced with one of the reserve aircraft from Hobsonville, K8558.

The Achilles carried out a further Pacific Island cruise in June‑July 1938.

Walrus K5783 was the ship’s aircraft for that cruise and was frequently catapulted off the ship to provide training for the ship’s and aircraft crew.

On 24 November 1938, Leander anchored off Christmas Island and Lieutenant Nicholl took Walrus L2222 and members of the survey party on a reconnaissance around the island.

When the Walrus was catapulted off the cruiser, however, the catapult cradle became detached and fell overboard.

This restricted further Walrus flights to situations where it could be lowered over the side by crane into calm waters.

For recovery the standard practice of the ship creating a slick was employed. HMS Achilles had now finished her New Zealand tour and on 2 December 1938 sailed for England.

During the mid-Atlantic crossing, Achilles encountered a severe storm. The wind was so strong that the Walrus propeller rotated for about 36 hours and fabric had torn off both mainplanes and tailplane, exposing the metal structure.

On 21 February 1939, Achilles sailed to the Mediterranean for working-up exercises with the fleet based at Malta.

Loaned RAF maintenance personnel were on board to look after Walrus L2241, the replacement Walrus. Achilles left Malta on 20 March for New Zealand via the Suez Canal.

During her passage from Aden, Walrus L2241 was lost in the Indian Ocean, on 1 April 1939.

Sub Lieutenant (A) Eric Sykes RN carried out a routine flying exercise that fine Saturday morning.

The aircraft was hoisted over the ship’s side at 8.40 a.m, after which the ship steamed away at high speed. Accompanying Sykes as crew were two New Zealanders, TAG Peter Trent and Robert Stewart.

Sykes commenced a take‑off on the long‑swell oily sea surface, approximately one mile from the ship. The aircraft was seen to make two unsuccessful attempts to rise out of the water.

On the third attempt the aircraft became airborne rising to about 50 feet, but could not gain lift in the hot tropical air, and crashed heavily back onto the sea, damaging the port float. Peter Trent was dispatched to the starboard wing to counterbalance the port wing.

Turning and using engine power, the pilot tried, without success, to keep the damaged wing out of the water and the crew readied the aircraft’s inflatable raft.

Not sighting an airborne Walrus, the captain of the Achilles turned back, and when the ship’s crew saw the aircraft was in trouble, Achilles manoeuvred closer to the Walrus. As the ship approached, the list of the aircraft increased and at 9.06 a.m. it capsized, rolling onto its port side.

Stewart had by this time launched the inflatable raft and the crew quickly climbed aboard.

The ship’s boats tried to secure the partly submerged aircraft, but its weight nearly caused the capsizing of the boats, and it had to be cut free, to sink into the Indian Ocean.

The accident was thought to have been caused by the float on the lower port mainplane being shorn off during one of the bounces on the last take‑off run, followed by damage to the port wing fabric that allowed the wing to fill with water.

No disciplinary action was required against the pilot, but the Board of Inquiry concluded that Sykes should be directed by the Naval Board to exercise more care in future.

In early July 1939, after two months in Auckland and with a replacement Walrus (K5783), Achilles left for another Pacific mission, carrying the Governor‑General Lord Galaway and family on an island cruise.

While at Aitutaki on 15 July, the new Walrus, crewed by Sykes and TAG Peter Trent, safely launched for a local flight, zooming low over the admiring locals gathered at the edge of the lagoon.

The pleasant day, however, was marred by the recovery Achilles carried out a sweeping turn to create a slick and the Walrus alighted safely, and then taxied to the ship for the hoist aboard.

Peter Trent was on the upper mainplane to attach the crane hook and tricing wires and the hook was lowered and connected. From the accident report it appears that the automatic locking grab on the lifting mechanism failed to mate correctly.

At the same time the pilot saw the deck officer give the hoist signal, and cut the engine. The deck officer later stated he had not given the signal.

With the engine cut, and because it was not being lifted clear of the water, the aircraft veered outboard to the extremity of the reach of the cranes wire and commenced a nosedive.

Trent attempted to activate the emergency quick-release coupling but could not remove the locking pin. The aircraft was standing on its nose and capsizing as the tricing wires pulled it over.

The grab line parted with the aircraft, now upside down and partly submerged. Sykes was flung clear and Trent, after slipping out of his safety harness underwater, struggled to the surface.

The Achilles’ engines went full astern; the ship stopped, and immediately lowered a whaler to rescue the crew of the Walrus. With crew recovered, a grass hawser was made fast around the tail of the aircraft to haul it up with the crane, but the hawser slipped and, as the official report states, ‘the aircraft sank then and there’.

On the return of Achilles to Auckland, there was no immediately available replacement for the lost Walrus.

War Begins

The year 1939 saw the world plunged into global conflict.

As war became inevitable, the New Zealand Government sped up the programme to improve its Defence Forces.

One activity was an RNZAF expansion programme for an aircraft assembly and repair depot at Hobsonville.

In March 1939, the Naval and Air Boards agreed that permanent shore facilities were required to maintain the Walrus aircraft, and when completed, the RNZAF Repair Depot would be responsible for the third and fifth 120‑hour inspections and complete overhauls of the Walrus.

FAA squadron personnel at Hobsonville would carry out maintenance and other 120‑hour inspections, between cruise inspections, and anti‑corrosion measures.

The Air Board agreed to provide, at Hobsonville, hangar space for four Walrus aircraft and accommodation for two officers and ten naval airmen.

The final changes to the organisation of the Walrus Flight came on 28 March 1940, when the New Zealand Naval Board agreed to restructuring carried out by the RN, which combined all FAA catapult aircraft into one nominal squadron, numbered 700.

For the New Zealand Division, this meant a title change to No. 700 Squadron New Zealand Flight.

With the deteriorating international situation, Achilles was dispatched on 29 August 1939 to join its designated war station as part of the RN West Indies Force.

Sailing via South America, Achilles became part of the British Naval force in the epic Battle of the River Plate in December 1939 ‑ without an aircraft to undertake the important tasks of reconnaissance ahead of the fleet and spotting for the ship’s guns.

Coincidentally, the Walrus crew and RAF maintenance personnel were on board Achilles, even though they had no aircraft to look after!

It was later commented that the lack of a reconnaissance aircraft had allowed at least two enemy merchant vessels to reach Chilean ports unnoticed when Achilles was mounting a patrol off Chile just prior to the battle.

After the battle, Achilles proceeded to the Falkland Islands, where the FAA component on the ship disembarked to join others at Port Stanley.

Here a Walrus aircraft, L2236 from the cruiser HMS Cumberland, was taken over and manned by Achilles crew for patrols over the Falklands.

On its return to New Zealand Leander was engaged in troopship and convoy escort, and in February 1940, after the return of Achilles, sailed to Sydney to join other ships for further convoy escort duties, with Walrus L2330 as its aircraft.

Leander was then detached to join the British Fleet in the Red Sea to carry out protection duties for the convoys up and down the Red Sea to the Suez Canal.

This monotonous but essential work went on for six months, with cautious submarines and high‑flying Italian bombers providing some action from time to time.

In fewer than five months the cruiser steamed 30,874 miles and escorted 18 convoys with a combined total of 396 ships of approximately 2.5 million tons.

Two submarines provided the Leander with a mixture of both failure and success. On 16 June, an 8,125‑ton Norwegian tanker, the James Stove, was torpedoed and sunk about 12 miles south of Aden.

The cruiser’s Walrus amphibian made an unsuccessful search for the submarine, a hunt spoiled because report from a Royal Navy ship that a conning tower had been spotted failed to reach the aircraft.

Similar patrols flown during the next two days were equally unrewarding.

A minesweeping trawler, HMS Moonstone, was more successful having sighted a periscope, she dropped two depth charges and forced submarine to surface.

After a brief exchange of fire the submarine surrendered and was towed to Aden, where she was found to be the 880‑ton Galileo Galilei. On 27 June, the Leander met the destroyers Kandahar and Kingston and the entered the Red Sea, acting on a report that the destroyers and the escort ship HMS Shoreham, had made an almost certain successful attack on a submarine close to the southern coast of Eritrea.

After a two‑hour search the destroyer found the submarine aground and was ordered to attack it. An enemy aircraft was then sighted but it flew off when the ships opened fire.

The Leander’s Walrus was catapulted off to attack the submarine. Of its four bombs, one fell abreast of the conning tower, two were ‘over’ and the fourth would not release from its carrier.

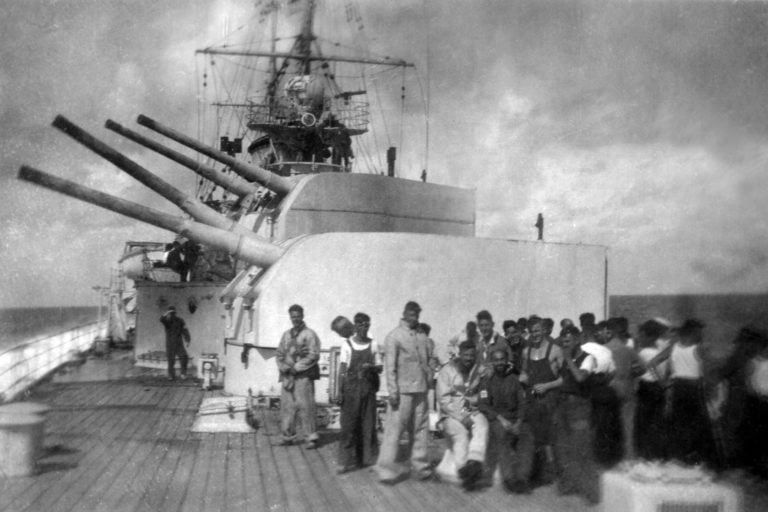

The amphibian was then ordered to fly clear and the cruiser opened fire with her main armament. The submarine was straddled four times before the Leander ceased fire.

The Walrus then flew over the submarine and found her well holed, with an oil patch extending from her for some distance. The submarine, later found to be the Evangelista Torricelli, a sister ship of the Galileo Galilei, was the fifth Italian submarine destroyed or captured in just eight days.

Among her other duties, the Leander kept a sharp lookout for German commerce raiders reported to be operating in the Indian Ocean.

It was not until February 1941 that she sighted a suspicious‑looking ship, but it was not German. It was the Italian Ramb I, a 3667‑ton twin‑screw merchantman armed with 4.7‑inch guns and anti‑aircraft machine guns.

Luck was with the Leander as she challenged the Italian ship, for she laid a broadside on and only 3000 yards away, a sitting target for either guns or torpedoes.

When the Italian vessel did open fire her shooting was both short and erratic. By contrast the Leander got off five salvoes in a minute, inflicting damage that caused the Ramb I to catch fire, blow up and sink.

On 29 November 1940, Leanders Walrus was again on operations, this time undertaking a bombing mission on an Italian wireless station and canning factory at Banda Alula in Italian Somaliland.

It was launched at 10.30 a.m., first to dive‑bomb the wireless huts, then to strafe any aircraft seen on the nearby landing ground, and to look for the ship’s bombardment. No aircraft were seen and although one of the aircraft’s 250‑lb bombs fell close to a radio hut, it was not close enough to put the station out of action.

After signalling the Italians to evacuate the canning factory, Leander’s shells reduced it to rubble, with the Walrus dropping a few incendiaries for good measure.

During early 1940, Achilles was steaming around New Zealand waters providing convoy protection and reconnaissance of outlying islands in search of German surface raiders.

Three months later, Achilles was again sent on a rescue mission, this time to collect survivors from the passenger liner RMS Niagara, which had struck a German mine near the Hen and Chicken Islands.

With mines now definitely present in New Zealand waters, the Walrus was launched more frequently when the ship was nearing ports, flying ahead of the cruiser to spot mines in the approaches, areas favoured for mine laying by German raiders.

Shortly after, on a reconnaissance trip to the Kermadecs, poor weather conditions prevented the use of the Walrus, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the search.

The Achilles Walrus was launched, however, for reconnaissance of Perseverance Harbour during a trip to Campbell Islands on 20 November.

The pattern of activity for the Walruses on the two New Zealand ships had now become routine. Achilles carried out convoy escort and reconnaissance of New Zealand waters and Leander was on operations in the Indian Ocean, but Walruses were seldom launched on the high seas.

Reconnaissance of approaches to ports and outlying islands was now their forte.

By the end of August 1941, the Walruses at Hobsonville had increased to four.

In late September Achilles and Leander were back in New Zealand, just in time for the entry of Japan into the Pacific War on 7 December.

The two cruisers and their aircraft were now assigned for a short time to a combined ANZAC Naval Force under the command of Vice‑Admiral H.F Leary USN.

Their duties were close‑escort, shepherding convoys of troopships and supply vessels to and from the New Hebrides and Noumea (New Caledonia). From February 1942 both ships came under the command of Commander South Pacific, Vice‑Admiral Ghormley USN.

In most cases, RNZAF, USN or RAAF land‑based aircraft provided air cover as far as their respective ranges allowed. By this time the Walrus was being overtaken by technology and the pace of this new war.

Improved radar systems on the larger ships, including Achilles which had a New Zealand‑made set), gave a detection capability better than could be achieved by the visual reconnaissance of the Walrus.

Convoys and other large groups of ships were now often accompanied by an Aircraft carrier, with aircraft more suited to providing aerial cover, spotting and reconnaissance than the antiquated Walrus.

Hobsonville‑based Walruses were kept busy with crew-training flights and carrying personnel and supplies to the islands in the Hauraki Gulf.

A further diversion was trialling airborne Air‑Surface‑vessel (ASV) radar equipment developed by the DSIR in Wellington.

Radar gear would be fitted to a Walrus and the aircraft carrying the ‘boffin’ would ‘chase’ various ships and targets around the Hauraki Gulf. In September 1942 the official aircraft disposition statement from Hobsonville noted that K8558 still had ASV fitted.

Even though the Walruses were nearing the end of their carriage on the cruisers, there were still occasions when they got into a ‘bit of strife’. Temporary Sub Lieutenant (A) William Billings, a pilot on Achilles, recalls two such incidents.

‘On 31 July 1942 in Pago Pago Harbour, Billings and his crew were harassed by a Squadron of eager American fighters, they ran for the cover of the Achilles and the fighters departed.

The other incident occurred in Brisbane, on 20 August 1942. On a routine continuation training flight and having verified all procedures, they caused the first air raid alert in Brisbane, even the Prime Minister was in the air raid shelter”.

They made the front page of the paper.

The days of the shipboard Walrus were now over. In September 1942, Achilles underwent a major refit at the Devonport Naval Base and the catapult was removed.

Leander followed suit in November and, with the removal of the catapults, No.700 Squadron New Zealand Flight was no more.

The remaining Walruses were transferred to the RNZAF, to commence a new career as training aircraft for maritime aircrews.

The Walrus will long be remembered by naval pilots, if only for the unforgettable noise made by its 18 open exhaust ports, and its flying characteristics have never been better described than by Terence Horsley in his book Find, Fix and Strike:

Turns are made with slow dignity, as one might imagine a 60‑seater bus on a smooth road. Pipes and tobacco come out, the transparent panel is slid over our heads, but the side window is left open for fresh air. The engine makes a steady roar but sufficiently above and behind us to make conversation possible. On a rough day the Walrus behaves more like a cow than a bus‑a very friendly cow however. She wallows in the trough of the rough airs as a heifer knee deep in a boggy meadow. Her driver has a certain amount of heavy work to do in pushing the wheel around but he is reassured by the steady roar of the one and only Pegasus engine.