Interview conducted – April 2019.

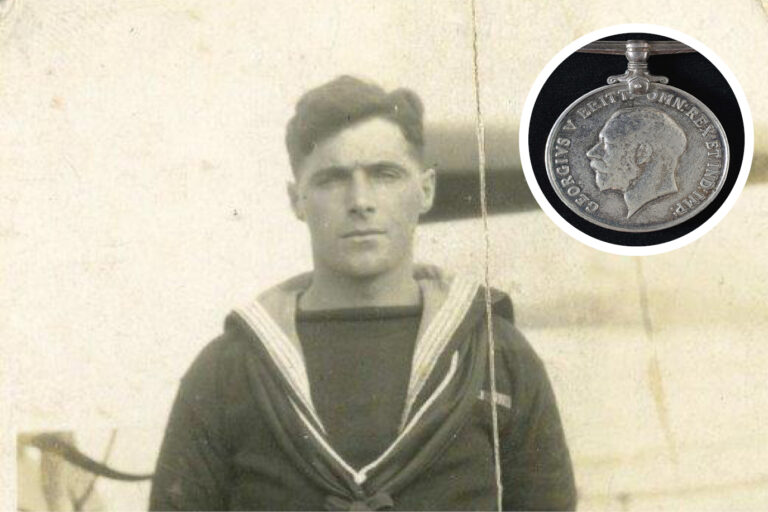

Without the Navy ninety-three year old Brian Breen suspects he may have become a typical troublesome teenager. It was 1942, the Japanese as Brian puts it were knocking on the door and he was determined to do his bit.

After some serious persuading, Brian’s father finally gave his permission for the 16 ½ year old to join the RNZN. He recalls his time at HMNZS Tamaki as a bit of a shock.

Naval training in the 1940s

“A favourite punishment doled out to trainees was taking ‘Jimmy for a walk’. HMNZS Tamaki was set up on a hill on Motuihe Island, so we had to roll ‘Jimmy’ the 112 pound, 6 inch shell down the hill and then carry it back up! I didn’t have pleasant thoughts about our instructor at the time. However, he later became a much respected Petty Officer Gunnery Officer,” remembers Brian.

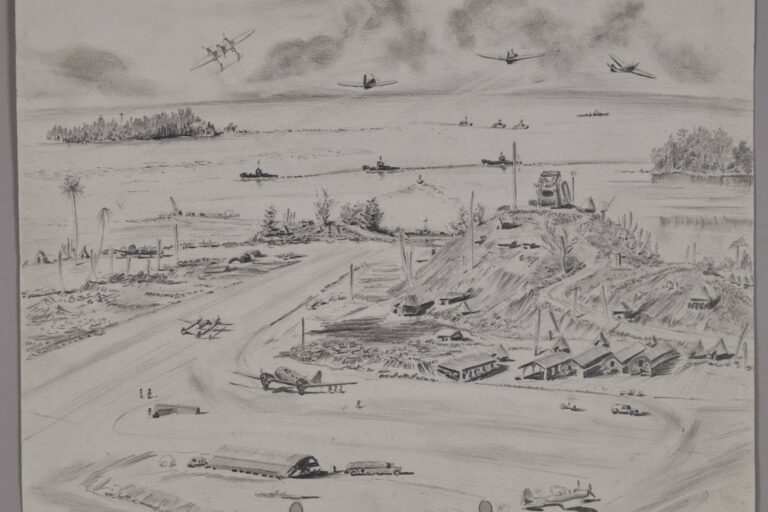

Noumea

Brian’s first posting was to HMNZS Leander, travelling to Noumea in April 1943 to join the crew as a Seaman Boy First Class. He spent the next few weeks at a US Naval base on the island with a group of young sailors awaiting the arrival of Leander. The group spent their time joining work parties and swimming at nearby Anse Vata Beach. A lack of funds was an ongoing problem for the young seamen but Brian recalls one young sailor’s attempts to ‘ease their suffering’.

“Harry started a grog running business. He collected dollars from the willing US Navy members and then in spite of his limited French managed to purchase bottles of questionable quality liquor from local ‘slog groggers’. He’d hide these around the perimeter of the camp to be retrieved and distributed later to the ‘investors’. Harry’s business flourished until the evening when he’d sampled a bit too much of his own product and was found wandering outside his tent, was arrested and spent a day or so in the ‘brig’. So ended a promising business venture.”

Brian also remembers visits by entertainers and bands to the camp.

“The most notable for me, anyway, was Artie Shaw and his band I well recall his drummer practicing rhythms on a solid block of wood outside a tent.”

Off to sea

Leander arrived in Noumea in late May 1943 and so began Brian’s first sea posting.

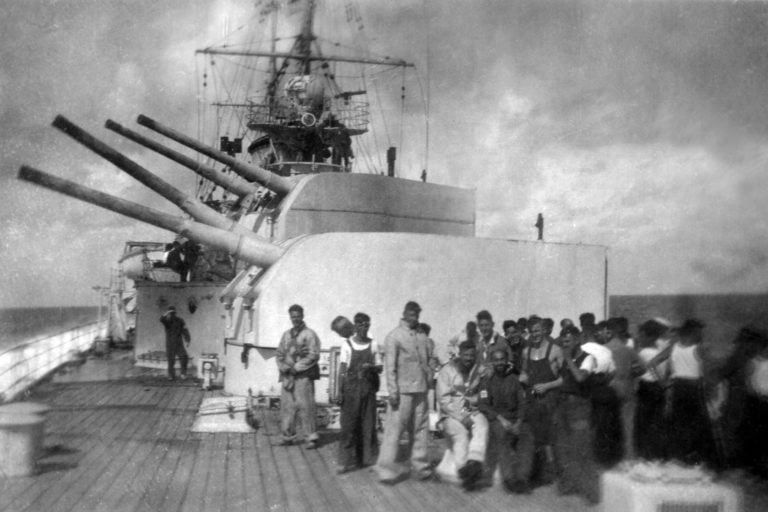

Life on Leander included regular (and at times unpopular) damage control drills led by the ship’s Executive Officer Stephen Wentworth Roskill, known as the ‘Black Mamba’. Whilst somewhat unpopular, CDR Roskill’s tenacious attention to detail was to prove invaluable, just a short time later when Leander joined US Task Group 36.1. Leander replaced USS Helena sunk at the Battle of Kula Gulf on 6 July.

Brian was post forward lookout on the bridge on Leander off the coast of the island of Kolombangara on the evening of 12/13th July, 1943. Seventy–six years may have passed but Brian’s memory of the moment a little after 1am on the 13th July, when a Japanese Long Lance torpedo struck Leander ripping a hole twenty feet by 30 feet remains crystal clear.

The Battle of Kolombangara

“There was an almighty thump as we lifted and lurched,” remembers Brian. He is keen to set the record straight that the ship didn’t lift ’10 feet’ as has been detailed in some reports.

Leander had departed Tulagi earlier that evening with American cruisers USS Honolulu and St Louis and ten destroyers as part of Task Group 36.1. Their orders were to intercept the Japanese force spotted earlier in the day by coast watchers heading towards Kolombangara and prevent the destroyers from landing men and supplies, referred to by the Allies as the ‘Tokyo Express’.

At 11pm all the ships were ordered to action stations. At 12.30am on the morning of 13 July, an aircraft advised the task group that a cruiser and five destroyers had been sighted heading towards the group. Speed was increased to 28 knots and the forces approached each other on reciprocal courses in the darkness.

Unknown to Task Group 36.1, an hour earlier the Japanese had detected radar signals from the approaching ships. However, it wasn’t until 1am that the Task Group had a visual sighting of the Japanese ships, immediately opening fire with their guns and torpedoes.

On the bridge

Up on the bridge, Brian had a bird’s eye view of HMIJS Jintsu when she inexplicably turned on a searchlight making herself a target for all the gunners. Leander fired 160 shells at the Japanese cruiser which having taken a heavy pounding was quickly wrecked. The five destroyers accompanying Jintsu quickly fired 29 of their fearsome Long Lance torpedoes towards the Task Group ships.

“Our Talk-Between-Ships voice radio system had failed so we’d missed the order from Admiral Ainsworth to make a simultaneous 180 degree turn south. We ended up as tail-end Charlie having to take last minute evasive action to avoid a collision with USS Honolulu, who belatedly was following orders to turn to port. It was at this point the Japanese torpedo found its target.

“The tremor through the ship must have flipped the shutters on one of the searchlights open, flooding light into the water, lighting us up for all to see. Luckily the searchlight’s crew sprung into action quickly breaking the circuit and averting more danger. We had no light and no power. I knew I had to stay at my post, I wasn’t scared; I was too pumped up with adrenaline. I remember thinking are we going to stay afloat – our life jackets didn’t look too good,” remembers Brian.

After the battle

Only when he came off watch several hours later, did Brian realise how close the ship had come to sinking.

“My usual relief, Bill Clyde didn’t arrive, sadly he’d been part of the gun crew blown overboard when we were hit. They were never recovered.”

Twenty eight men from HMNZS Leander lost their lives that night.

Brian acknowledges the tireless efforts of CDR Roskill and his crew mates, with everyone working 18 hours non-stop to enable Leander to limp back to Tulagi where they temporarily patched the damaged ship.

A poignant memory for Brian is the memorial service held on the forecastle later that evening. Prayers for the dead and of thanksgiving were read along with the names of Brain’s crew mates killed and missing. A further service and burials were held later the following morning at Tulagi. Once back in Auckland for repairs, Brian and his crew mates were sent on leave whilst others carried out the difficult and no doubt harrowing task of removing the remaining six bodies left entombed in the boiler room since the attack.

Achilles and Arabis

Brian remained on Leander when she journeyed to Boston for repairs, later joining HMNZS Achilles serving off Formosa during the landing on Okinawa and off Japan when the A-bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He finished his service with RNZN on the minesweeper Arabis re-sweeping for mines laid by the Germans off the Mercury Islands area.

Civilian life

Having done ‘his bit’ Brian left the Navy in 1947, and settled into a career in teaching that was to last 35 years with his last role as deputy principal of Manurewa West Primary. An active member over many years of the Papatoetoe RSA, Leander and Achilles Association, Brian’s only regret from his time in the Pacific was that he didn’t get to land in Japan.

Brian is proud to have inspired a new generation. Grandson Matthew graduated as a Marine Technician in the RNZN in 2018, a very proud moment for Brian. Asked what he took most from his time in the Navy Brian thought for a moment then said, “The people you meet. As a teenager I met some of the finest young men you could ever hope to meet.”

Brian Breen passed away September, 2021 following a short illness. He was 96 years old.