All officers and ratings aboard HMS New Zealand were subject to The King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions as related to offences and corresponding punishment. Both of these documents specified rules and punishments for any infractions of the rules or orders. Note that while flogging as a physical punishment was long gone by 1913 but still remained on the books. There were different levels of crime and the methods of punishment. Delivery of punishment relative to the offence within the regulations as set out was subject to whims of the Commanding Officer and the Regulators[1] charged with administrating punishment. The overwhelming principle of naval discipline is the “maintenance of good order and discipline”. This catch-all phase covered many forms of ill-discipline and offences. No ship could afford to be slack in its discipline given the nature of a warship in commission and a Commanding Officer was judged by his discipline record. The key was to be firm, fair and consistent but with an application of common sense. This is more of an art than science and was part of effective leadership. There is a sense of paternalism in the actions of the Royal Navy in this period towards those ratings under command. Also to that the Commanding Officer had absolute power over all officers and ratings serving in his warship. A poor officer could break a ship while a good officer would make a ship.[2]

The lower deck’s attitude to punishment was to accept that punishment was a fact of life in the Royal Navy and general attitude was “they could take what the navy was prepared to serve out.”[3] It is worth noting that on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers discipline was much more rigid that in smaller vessels such as destroyers, minesweepers or submarines. ‘All ratings explicitly recognized that discipline – even severe and strict discipline, so long as it is neither excessive to the point of sadism nor capricious in its application – is essential to the effective performance of the naval mission; it maximises the safety of all who go to sea in a ship.’[4] Remember this was peacetime discipline. When the RN went to war the punishments could include execution and disobeying an order carried much more severe consequences than it would have in 1913.

What type of offences could require punishment?

- disobeying a direct order from a senior rating or officer

- conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline – a catch-all charge

- striking a senior rating or officer

- desertion aka “run”

- homosexual encounter with a fellow rating

- failure to keep personal kit in order

- failure to look after ship’s boat or other equipment that a rating is responsible for

- theft

- breaking leave

- drunkenness

- absent without leave [AWOL]

- fighting

- failure to follow standing orders aboard ship

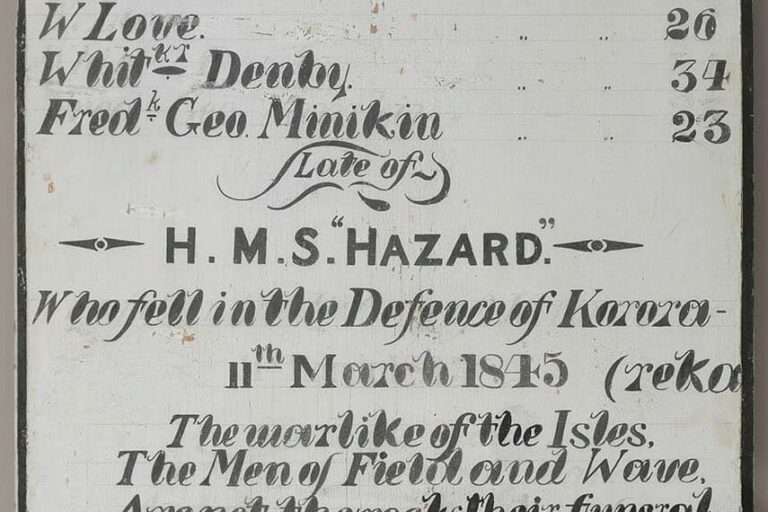

In the case of the 30 April 1913 note in the ship’s log. These three men committed an offence and were sent to the on-board prison to serve a term determined by the Commanding Officer. They would also be given extra duties aboard ship, especially menial cleaning tasks.

In September 1912 new rules were issued by the Admiralty with regard to the system of summary punishments laid in The King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions. This included reducing men in rate or class of rate for the following:[5]

- gross insubordination

- dishonesty [retained in the Navy and not discharged]

- “…continual slackness or other misconduct the repeated award of minor punishments have proved ineffective.”[6]

Boy seamen aged seventeen and under were subject to corporal punishment from the instructor officer. While corporal punishment had been abolished for adult ratings, this reflected society’s attitude to discipline for children.[7] Methods of punishment and types of offences were outlined in The King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions.

Two types of physical punishment could be inflicted. Canning with a metre long cane about 1.5cm thick. Offenders could be sentenced to six or twelve strokes or “cuts”. The seamen boys would be assembled to witness punishments on the deck or at time it would be held in a closed off space. The Master-at-Arms, the surgeon, Ship’s Corporals and officers would be witnesses at either venue. The second type could be birching using a bundle of birch branches/. This was reserved for serious offences such as desertion, theft, or striking a senior rating. Usually twelve or 24 “cuts” were delivered. In this case the entire ship’s company would be assembled to witness. In both types of punishment the offender was bent over a part of a ship or vaulting horse if one was aboard. [8]

For adult ratings aged seventeen and above there were a range of methods of punishment. Minor offences by ratings and boys were dealt with by the Officer of the Watch who would issue punishments such as extra duty or corporal punishment in the case of boys. Those of a more serious nature were brought before the Executive Officer who held a ‘defaulters’ session each morning. A range of punishments could be issued including imprisonment aboard ship.[9] If the offence was thought beyond the Executive officer’s power there was a father step in the discipline process. Men who committed serious infractions when in harbour or at sea would have to report to the Captain’s Table. The Commanding Officer who would be advised of their offence and issue punishment which would include deduction or stoppage of pay, stoppage of leave, confinement aboard ship, extra duties [including menial tasks]. The Commanding Officer could at any time muster men under punishment and instruct them to be given extra drill in the dog watches but not to exceed one hour a day.[10] Commanding Officers could send a rating ashore for three months to a RN detention barracks on their own authority with no oversight. These barracks were harsh and uncompromising in their discipline. This was intended to ensure that no sailor had a return visit.[11] Ratings would also be subject to a court-martial held aboard ship if the offence merited it. For example, in 1914 on the armoured cruiser HMS Kent an Able Seaman who struck a Petty Officer after returning drunk from shore leave. He was court-martialled aboard the warship. The court found him guilty of the charges and he lost his three good conduct badges and spent 90 days in the cells. Losing his badges also reduced his pension and pay. This sailor had spent eighteen years in the Royal Navy.[12] Dismissal with disgrace by Court-martial was the ultimate penalty.[13]

Officers had a different form of discipline. Any breaking of The King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions would usually result in the officer being removed from the warship and posted ashore to a menial task. If the offensive was more severe then the officer would face a court-martial and be punished accordingly – this could include mishandling of a ship’s boat or the grounding of a warship Officers would be dismissed from the Royal Navy and cashiered. This placed a barrier to the disgraced officer and society and made it a lifelong punishment. Social punishment by disgrace was felt to be a risk that an officer ran in 1913. Ratings however thought that officers were punished to a lesser degree and in the highly structured class system of Edwardian Britain did not perceive the shame and damage to career a court-martial could bring to an officer.

Desertion in the Royal Navy

Desertion is a part of naval life. In naval terns it is recorded and as ‘run’ of ‘running’. Sailors could always find reasons to stay behind when the ship left a port be it women, a job ashore or just had enough of the life in naval service. In some ways it was easier to desert in the Navy as opposed to the Army because if the ship was overseas a sailor could disappear. Some men realising they were not cut out for shipboard life would look for an opportunity to escape. The usual way was to not return to ship when in port and hide out until it left and merge into the local community to start the deserter’s new life. Losses of men would be discovered when divisions were held and rolls taken or the man was noticed as missing and reported. It would then be the Master-at-Arms [Regulators] to search for the man and bring him back. They could always be discovered by the authorities and if they were apprehended, returned to naval custody and then for punishment aboard ship by court-martial. Imprisonment aboard ship or being sent to the detention barracks would be the usual way deserters were punished. They would also lose a rate and/or good conduct badges if they had any. Men joined the Royal Navy in 1913 for a minimum term of twelve years and many had cause to regret their decision.[14] They were treated as military criminals and punished accordingly.

[1] This was a nickname for those ratings aboard ship charged with maintaining discipline and enforcing it. They would also administer punishments or detain offenders. They were not the most loved men serving in the ship.

[2] Peter Padfield, Rule Britannia: The Victorian and Edwardian navy, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, pp. 51-53

[3] Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900-1945, Cambridge: Harvard University press, 2002, p. 43.

[4] ibid., p. 44.

[5] Circular Letter No. 32 issued 7 September 1912: Viscount Hythe (ed.), The Naval Annual 1913, Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co., 1913, pp.447- 448.

[6] ibid., p. 448.

[7] Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900-1945, Cambridge: Harvard University press, 2002, pp. 40-41.

[8] ibid., pp. 40-42.

[9] Peter H. Liddle, The Sailor’s War 1914-18, Poole: Blandford Press, 1985, p. 131.

[10] Circular Letter No. 32 issued 7 September 1912: Viscount Hythe (ed.), The Naval Annual 1913, Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co., 1913, p. 448.

[11] Christopher McKee, Sober Men and True: Sailor Lives in the Royal Navy 1900-1945, Cambridge: Harvard University press, 2002, p. 40.

[12] ibid., p. 205.

[13] Peter H. Liddle, The Sailor’s War 1914-18, Poole: Blandford Press, 1985, p. 131.

[14] Later on in the 20th century it was reduced to eight years and then four years.