HMS Veronica arrived in Napier ahead of schedule on February 3, 1931. Though she wasn’t expected until the afternoon, she tied up in the harbour at 7:50 a.m. Shortly before 10:45, Veronica’s captain, Commander H.L. Morgan DSO, met with the harbourmaster to organise his official visits of the day. What happened next resounded all around the country. It brought Napier to her knees and altered the course of Veronica’s routine visit.

HMS Veronica arrived in Napier ahead of schedule on February 3, 1931. Though she wasn’t expected until the afternoon, she tied up in the harbour at 7:50 a.m. Shortly before 10:45, Veronica’s captain, Commander H.L. Morgan DSO, met with the harbourmaster to organise his official visits of the day. What happened next resounded all around the country. It brought Napier to her knees and altered the course of Veronica’s routine visit.

At 10:46 am on 3 February 1931 an earthquake registering 7.8 on the Richter scale shook throughout New Zealand, its epicentre just 15.2 kilometres north of Napier. Commander Morgan described the event to the New Zealand Herald:

I was just leaving my cabin…when I heard a terrific roar. The ship heaved and tossed. For about ten seconds I stood still and then ran on to the boat deck. I could see houses falling and roads cracking. Everything seemed to disappear in a cloud of dust.[1]

The initial shock lasted for 2.5 minutes. In the city of Napier, buildings and chimneys toppled, roads broke apart and the earth heaved and opened. There was widespread panic among the survivors as they tried to find their loved ones in the wreckage and establish safety through the aftershocks.

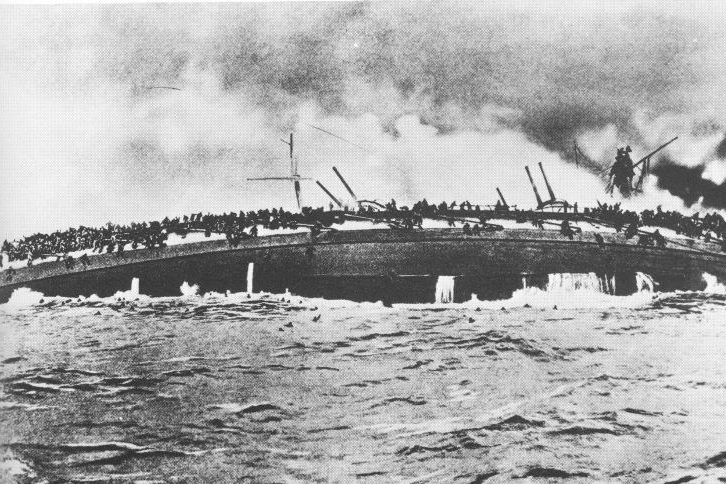

Water rushed out of the harbour as the ground rose. Veronica was ‘left high and dry, all the wire mooring lines broke, but the ropes, made from New Zealand flax, held, and prevented her from rolling over on her side.’[2] With her keel resting on the harbour bed, Veronica felt the tremors of the aftershocks. Nonetheless, the crew of Veronica were quick in their response to the disaster on land.

Commander Morgan landed rescue teams to assist the injured, feed the hungry and help establish a sense of order amidst the chaos. Fires were ablaze on shore, power and water supplies were cut and hundreds discovered they were homeless. Two merchant ships at anchor nearby, the Taranaki and Northumberland placed themselves under naval command and assisted in the relief efforts.

One of the most crucial early actions taken by Veronica was the message she sent to HMS Philomel, at the naval base in Auckland. At 10:54 Commander Morgan reported the disaster via Morse code to the Commander-in-Chief:

Am berthed at Napier. Earthquake 1045 lasted for about 3 minutes. Ship trembled violently and bumped jetty. Securing wires eased. No damage to Veronica.[3]

The communication continued as follows.

1114: From CCNZ [Commander-in-Chief, New Zealand Squadron]: Do you require assistance of cruisers.

1122: From VERONICA: Yes VERONICA hard and fast ashore.

1141: From VERONICA: Impossible to estimate damage fear extensive water rising had to draw fires am raising steam.

1141: From CCNZ: What assistance required.

1153: From VERONICA: Medical assistance required fear considerable loss of life.

1156: From VERONICA: Am landing all assistance possible.

1157: From CCNZ: Proceeding to Napier with Diomede with assistance.

1218: From VERONICA: Store buildings down fires raging everywhere all medical assistance possible required shocks still recurring.

1331: From VERONICA: Situation appalling whole town appears to be on fire.[4]

At 12:26pm Veronica sent out a general message for all to hear, ‘Serious earthquake at Napier all communications destroyed medical assistance urgently required.’[5]

By 3 p.m. the cruisers HMS Dunedin and HMS Diomede were loaded with emergency supplies including 54 stretchers, 5 marquees, 34 tents, 400 naval blankets, 125 seamen’s beds, 200 ground sheets, 80 shovels and 31 picks. Aboard with the ships’ crews were 11 doctors and 17 nurses.[6] Travelling at full speed (24 knots) down the coast, Dunedin and Diomede made best speed to Napier arriving at 8:30 the next morning.

The destruction they found at Napier was devastating. ‘Well it just looked like pictures I had seen of the First World War, of a town that had been bombed, it was mostly flattened, and burnt out. There were [only] a few wooden houses [standing],’[7] describes Stanley F. Parslow, who was serving as a stoker on the Dunedin. The crews joined the relief teams that had been at work for nearly 24 hours.

The Navy took charge of clearing streets and breaking down precarious remnants of buildings. They aided in the recovery of bodies. Others took up jobs to help support the stunned survivors. The town was searched for food and supplies. Food depots were set up in schools around the city, a telegraph station at the Hastings Street School, medical tents and make-shift shelters with ground cloths along the Marine Parade. Says one survivor, Agnes Bennett:

It was a pleasure to see the tents being set up with military precision – marines and bluejackets were in evidence and a good fire and a big oven gave promise… Volunteer workers were busy and the Nelson Park camp was the most promising bit of organising that one had seen. The dull expressionless faces were disappearing and life and interest had begun to return.[8]

The evacuation effort progressed steadily. By 7 February nearly 5,000 people were evacuated, some by ship, some by car, and others by train. Fires continued to threaten the town through the evening of the 5 February and the aftershocks continued on for many days.

Some of Napier’s services were restored very quickly: power was restored late on the 4th, a water treatment plant was set up on the 5th, and the first train was able to reach Hawke’s Bay on the same day. All this made relief and evacuation easier, but by no means put Napier back on its feet. Hastings and Wairoa had also been very badly damaged. In the end, the official death toll reached 256, with 161 dead in Napier, 93 in Hastings and 2 in Wairoa.[9] The naval chaplain from HMNZ Philomel, Reverend G.T. Robson (“Padre Robbie”) conducted the first funeral service for 54 victims at the common grave. It is to this day New Zealand’s heaviest loss of life n a natural disaster.

On the morning of February 10th, with the groundwork for recovery established, Veronica left Napier for Auckland.[10] Dunedin and Diomede left on the same evening. Napier would be reconstructing for another thirty years, through which time it gained new character and livelihood. The service offered by the Royal New Zealand Navy in those first few days was never forgotten.

Veronica Bell Ceremony

During Art Deco Weekend usually held in February, the citizens of Napier took to the streets in true Art Deco fashion to celebrate the flavour of their city. A variety of events took place from day to night, from concerts to lectures, movies to boat races. As in the past, the Navy was in attendance. HMNZS Resolution berthed at Napier for the weekend. The RNZN Band performed at the Sound Shell and at brunch where civilians dine with naval officers.

Also during the weekend is the Veronica Bell Ceremony, during which the ship’s bell from the HMS Veronica is paraded from Napier Museum to the Veronica Sunday in the Marine Parade gardens. A military ceremony is performed here in remembrance of those who died in the earthquake of 1931 and in celebration of the courageous relief parties. Each year on the anniversary of the disaster, the people of Napier and the Navy come together in remembrance with this ceremony. The Veronica Bell hangs in the Sunday for the day, guarded by Sea Scouts until the evening when it is taken to the Cathedral. The Ship’s nameplate and its bell, the Veronica Bell, were donated to the Napier City Council when HMS Veronica was paid off in the mid 1930s and remains a symbol of the comradeship between Napier and the Navy. The ceremony remembers those who died and celebrates the courage of those in the relief effort.

References:

[1] New Zealand Herald, 5 February 1931, p. 11.

[2] ibid., p. 12.

[3] http://www.rnzncomms.org Accessed 27 February 2009. See also Peter Smith, A History of Naval Radio Stations and Radio Facilities in New Zealand, 2nd ed., Auckland: Privately Published, 2008.

[4] Geoff Conly, ‘The Shock of ‘31’ in Thank God for the Navy: – The Navy’s Role in The Hawkes Bay Earthquake Napier, February 1931, New Zealand’s Greatest Natural Disaster, Auckland: Brebner Print, 2004, pp. 4-5.

[5] ibid., p. 5.

[6] Daily Telegraph, Hawke’s Bay: Before and After, Napier: Daily Telegraph, 1981, pp. 84-85.

[7] S.F. Parslow Oral History, DLA 0026 RNZN Museum, December 1990, p. 15.

[8] Matthew Wright, Quake, Auckland: Reed, 2006.

[9] https://teara.govt.nz/en/historic-earthquakes/page-6 Acessed 15 January 2025.

[10] She had her hull inspected on 9 February to determine if she was seaworthy.

![Amokura Training Ship Amokura [formerly HMS Sparrow]](https://navymuseum.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/amokura.jpg)