The United Nations Resolution on June 25, 1950 condemning the North Korean attack on South Korea and demanding their withdrawal by a vote of 9-0 in the Security Council was a unique event. They had come out in support of one faction over another. The result was the United Nations War in Korea, a coalition of forces led by the United States to repulse the North Korean invasion of its neighbour.

This is an edited version of an article written by Russ Glackin first published in issue 10 Winter 2010 of The White Ensign.

New Zealand’s Involvement

New Zealand’s involvement with the UN coalition in Korea was the result of an increased awareness of communist threats to it’s region’s stability. This led to greater focus on Asia and Chinese communist expansion in its defence planning thus providing the immediate context for the ANZUS Pact signed with the United States and Australia in 1951.

The war was a watershed in New Zealand’s security and defence arrangements.

The Failures of the Past

History is littered with examples of nations that have committed flagrant acts of armed intervention in the affairs of others, but it is only in modern times that the Great Powers have attempted to control the aggressive hostility of nations against others, by creating a system of international collective security to ensure lasting peace.

All have failed in the face of the inability to reach consensus on what constitutes a threat of peace.

The League of nations that emerged in 1919 from the Ashes of the Great War, soon became mired in sterile debate and failed to achieve consensus to halt the aggression of Fascist Germany and Italy in the 1930s. But the concept of international collective security again became a reality at the end of World War II with the creation of the United Nations.

The objective and the means to attain it, remained the same as in the past but, the UN too was destined to founder on the old problem of how to achieve Great Power consensus on international security. Aggressive, totalitarian communism was considered a major threat by western democracies but it was not an attitude shared by soviet Russia and communist China so any attempt from the UN Security Council to secure a consensus to blunt continuing communist expansion seemed doomed to failure.

Post-War Communist Expansion

In the years following the end of the War in 1945, Soviet-sponsored communism had advanced beyond an experiment in one nation to become an immediate physical threat in Europe, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East.

The western democracies were badly frightened by the disappearance of Eastern Europe under the cloak of Russian domination while Greece, France and Italy seemed close to collapsing into communist totalitarianism.

The West was reeling under the rapid communist expansion in the immediate post-war years. The United States had come to consider it increasingly likely that Soviet Russia would launch a hostile operation to test the will of the West probably in Berlin, Greece or Turkey. So, it came as no small surprise when the communists went to war in South Korea.

UN Security Council Reaction

The sudden North Korean military invasion of South Korea in 1950, was an act of blatant aggression of a nature not unfamiliar to history. However, in this case it was unencumbered by the political confusions, tangled international loyalties and conflicting motives that in the past had made collective, concerted intervention difficult, and thus it became a very real opportunity for the United States to blunt Soviet communist aggression.

When the United States received a request from South Korea on the 24 June 1950, for a delivery of arms to fight off the North Korean invasion, they made the decision to send the issue of the invasion to the United Nations.

The next day the UN Secretary General, Trygve Lie, was requested to call a meeting of the UN Security Council. The Council met at its temporary HQ at Lake Success that afternoon. The Soviet delegate, Yakov Malik refused to attend.

The Russians had earlier walked out of the Security Council in January, in protest, at the UN refusal to seat Communist China in place of the Nationalist Chinese of Chiang Kai Chek and were determined not to return. In the absence of the Russians and Communist China, a UN Resolution to condemn the North Korean attack, and call for the withdrawal of their forces south of the 38th Parallel, was passed unanimously by a 9-0 vote.

The UN intervention in Korea was thus “a fluke of history”. A consensus decision for collective action was made possible only by the absence of Soviet Russia; the unintended result of their boycott of the UN Security Council. For the first time, a collective decision had been made by an international organisation to intervene in a military conflict.

The United States pledged full support for the UN Resolution and President Truman agreed to enter the Korean War without consulting Congress, whose duty alone it is to declare war. It was a popular decision.

Armed with a second UN Security Council resolution calling on all UN member nations to assist South Korea and restore international peace and security to the area, Truman sought support among the United States’ principal allies and every other non-communist power, with the resources to make even a token commitment to the UN cause in Korea, now under the command of the United States Supreme Commander in the Far East, General Douglas McArthur. It was time for the West to stand up and be counted.

Why did New Zealand become involved?

Australia and New Zealand were quick to respond. Royal Australian Navy destroyers already on station in Kure in Japan, were immediately offered to the UN. They were joined soon after by a fighter squadron of the RAAF based near Hiroshima.

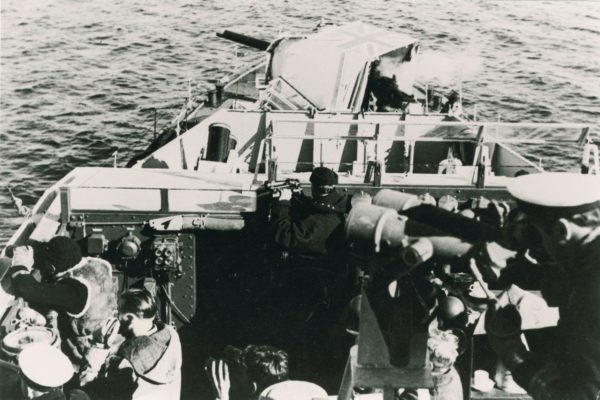

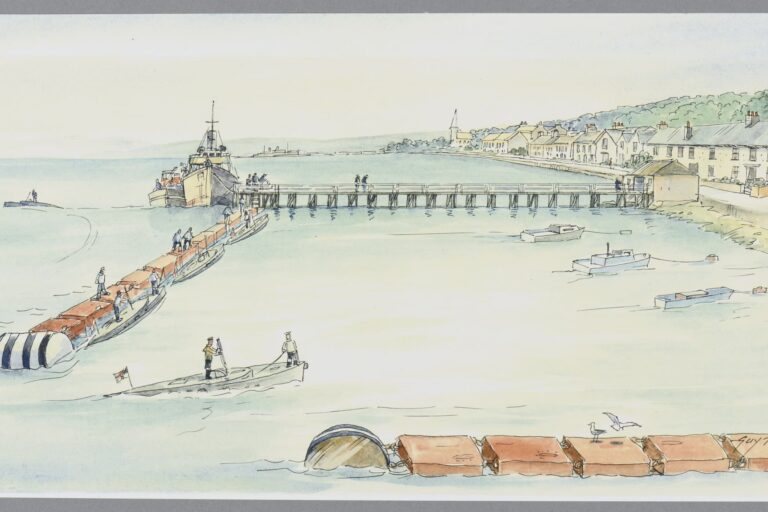

New Zealand offered two RNZN frigates, HMNZS Tutira and Pukaki. They departed Auckland on 3rd July, 1950 arriving in Korean waters 27 July.

The geopolitical landscape of the Asia-Pacific Region had been profoundly transformed by World War II. Britain emerged from the war with its power and status irreparably weakened and it could no longer defend its far-flung Empire.

Japan’s defeat had been achieved only by the United States. Added to these changes were the strategic realities of the post-war order. The Cold War had split the war-time coalition and had added the spectre of international communist expansion to New Zealand’s traditional fear of Asian aggression. It had also strengthened the perception that only the United States could ensure New Zealand’s security.

Collectively, these alterations to the world order demanded a reassessment of New Zealand’s security arrangements.

Immediately post-war New Zealand, initially clung to its traditional relationship with Britain. This was for reasons economic, as much as defensive, but now bolstered by a guarantee from its war-time ally, the United States. New Zealand’s security relied on Anglo-American co-operation in world affairs. The focus remained on Europe and the countering of a Soviet threat to Western Europe where the Dominion’s primary contribution would be as part of a Commonwealth force to defend the Middle East.

In growing contrast to Australia, New Zealand rejected any Asian focus, considering that it was too far away and only a threat if it fell under Soviet domination.

But Asia was changing rapidly. At the same time as the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, Britain was struggling to counter communist insurgency in Malaya and France and was at war to retain control of its Indo-Chinese colonies.

When North Korea invaded its southern neighbour, New Zealand interpreted the attack as part of a larger pattern of Soviet-inspired communist expansion and promptly contributed to the United States-led coalition, mobilised under the UN banner.

Quickly following the deployment of the RNZN frigates, New Zealand sent the 16th Field Regiment of Artillery to Korea, with the hope that it would eventually become part of a Commonwealth formation. They were followed soon after by an Australian infantry battalion (3 RAR).

The Commonwealth Force in Korea took some time to evolve, but when Britain proposed that its promised Brigade Group merge with the Australian and New Zealand contingents, a Commonwealth identity was firmly established among the other UN contingents in Korea.

Impact on New Zealand?

Participation in the United Nations War in Korea with the United States provided the context for New Zealand to acquire an American security guarantee, the ANZUS Pact of 1951.

The war in Korea did not bring an end to New Zealand’s traditional reliance on Britain for its security, but it led to a greater reliance on the United States and a greater focus on Asia, as a result of the growing apprehension about the expansion of Chinese communism.

References:

- Hastings, Max, The Korean War, Michael Joseph, London, 1987. P50

- Ibid P51