Britain’s Development of the Nuclear Bomb

By Russ Glackin – original article published in The White Ensign Issue 05, 2008.

In August 1945 the USA dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. This ended World War II in the Pacific. It also made the possession of nuclear power a major requisite for Great Power status in the post-war world. The British, no less than the Russians and French, scrambled to close what they saw as an alarming nuclear gap that had been opened by the Americans. So began a nuclear arms race that was the very essence of the Cold War. The seeds of Britain’s Operation Grapple in the South Pacific were sown.

Allies at Odds

British scientists had long conceived the concept of nuclear power. They were committed to the development of nuclear weapons. However, it was not until two nuclear scientists at the University of Birmingham published a paper in 1940 that the concept seemed feasible. The paper theorised on the source of the fast-chain reaction necessary for an atomic bomb. The Maud Committee was set up to explore how developing nuclear weapons might become a reality.

Scientists in the US were impressed by how technically advanced the British were. They pressed Roosevelt to set up the Manhattan Project, proposing to work with the British. Britain’s chilly response was ironically at odds with what would happen later. However, the British were concerned that the Americans would be unable to retain secrecy around such a project. They were also uneasy about the USA’s neutral position in the war at that point. In addition, they were understandably reluctant to surrender their nuclear advantage. It would be vital in the post-war world.

Britain needed America’s help to win the war. Churchill, accompanied by his daughter, travelled to America to request President Franklin Roosevelt to commit the USA to the war.

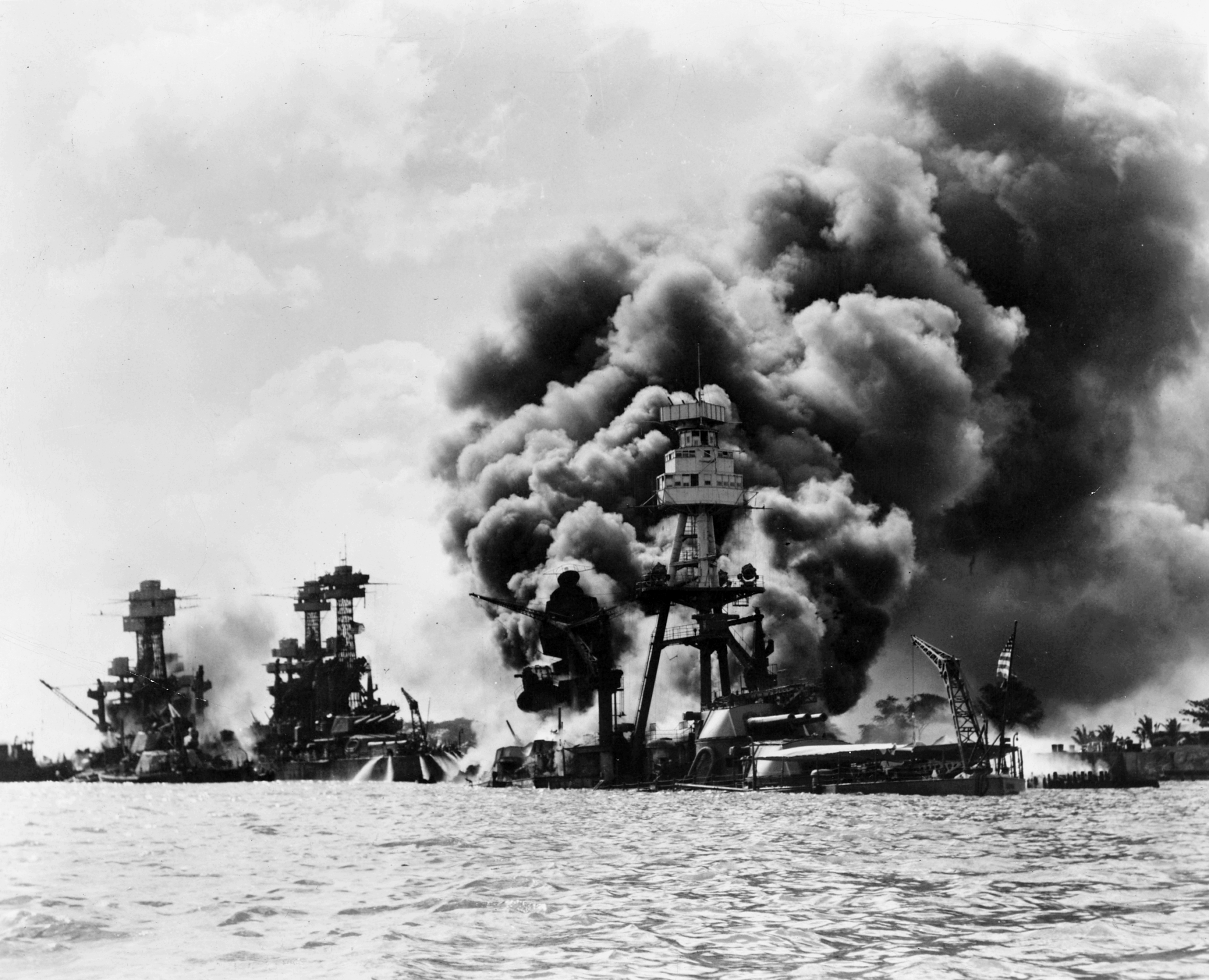

Pearl Harbour Bombing Galvanises America

American and British roles were dramatically reversed when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Roosevelt committed the USA to the war and to the atomic bomb. He poured vast quantities of money, materials and manpower into the Manhattan Project. A war-torn Britain could not compete.

Churchill’s formidable diplomatic skills were needed to persuade Roosevelt to give British scientists the opportunity to join the Manhattan team at Los Alamos. It was a desperate bid to build the bomb before the end of the war. Though the British scientists on the project were ‘compartmentalised’ by the Americans and prevented from getting an overall view of the work on the bomb, their contribution to the development of the Hiroshima bomb was vital. They returned home with a working manual on how to duplicate the American atomic bomb.

Successful testing of Britain’s megaton-range nuclear weapons during Operation Grapple required the cooperation of the three military services and civilian scientists. The four-pointed iron grapple symbolised inter-service cooperation on the project: Army, Navy, Air Force and the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE). The grapple is carried by a cormorant. This is a symbol frequently used to represent such inter-service cooperation.

This booklet was created for the information of the men who worked on Operation Grapple. The introduction by Task Force Commander Air Vice-Marshall W. E. Oulton suggests it would ‘serve as a pleasant souvenir of what must surely be one of the most interesting periods of your lives.’

Monte Bello Island Test Site in Australia

Britain’s priority was to explode a nuclear device as soon as possible. An isolated test site large enough to conduct 12 tests was needed. It should have no human habitation within 100 miles (161 km) downwind of a detonation. In addition, prevailing winds should blow contamination out to sea but not into shipping lanes.

In early 1952, Australia’s pro-British prime minister, Robert Menzies, readily agreed to allow Britain’s first atomic bomb test to be conducted on the uninhabited Monte Bello Islands off Australia’s north-west coast. Menzies was keen for Australia to start a nuclear energy programme of its own. He assured Australians that ‘the test… will be conducted in conditions which will ensure that there will be no danger whatever from radioactivity to the health of people or animals in the Commonwealth’. He neglected to mention that it was probably the first test in an ongoing programme and would leave the islands uninhabitable for years.

Britain secretly exploded its first A-bomb at Monte Bello at 9.15am on 3 October 1952. It went faultlessly.

Britain had joined an exclusive club but had singularly failed to impress its members. Only a month after Monte Bello, the USA exploded its first H-bomb, followed by the Soviets in August 1953. It was, however, the beginning of Britain’s programme of atmospheric nuclear tests that was to end with Operation Grapple Z on 23 September 1958.

New Test Sites Needed

The original test site on the Monte Bello Islands proved to be unsuitable. A further two new test sites were developed at Maralinga and Christmas Island. Maralinga is an aboriginal place name. It translates as ‘field of thunder’.

The test site at Maralinga was completed in early 1956 at a cost of five million pounds. At the same time construction had already begun at Christmas Island, which is now known as Kiritimati.

Developing a British H-Bomb

Britain decided to manufacture its H-bomb in June 1954 as the Americans and Russians had already developed and tested their H-bombs. They got a ‘bigger bang for their buck’ as the H-bomb was cheaper to manufacture than the A-bomb.

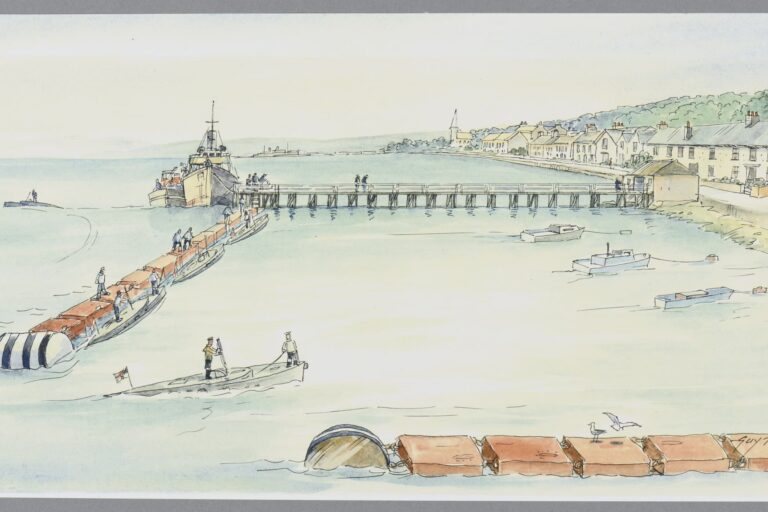

The original Test Agreement with the Australians had specifically excluded hydrogen weapon testing on the Australian mainland so the hunt was on for another testing ground. The requirements for the new site were that it should be under British ownership and in the largest area of the sea with the least number of adjacent land masses and the least number of people. The finger fell upon Christmas Island, the Pacific’s largest atoll, 1,000 miles (1,610 km) south of Hawaii, 1,500 miles (2,414 km) north of Fiji and adjacent to Malden Island.

The British H-bomb tests on Christmas and Malden Islands were code-named Operation Grapple.

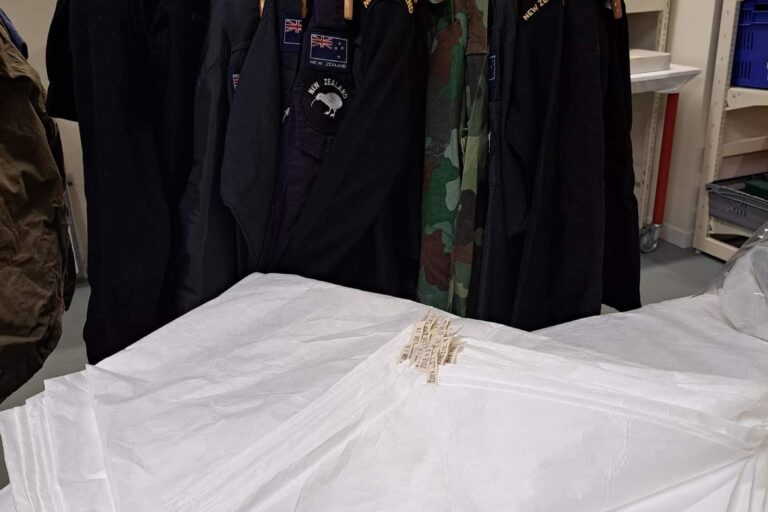

The period 1957–1958 saw direct New Zealand Navy involvement in nuclear testing. RNZN sailors were deployed at the request of the British to witness the nuclear testing off the coasts of Christmas and Malden Islands in the Pacific.

These tests were the final block carried out by Britain in Australia and the Pacific. Five hundred and fifty one men and two frigates, HMNZS Rotoiti and Pukaki, made up New Zealand’s contribution. Official duties were to witness the explosions and collect weather data. Some New Zealand sailors also monitored the test area for Russian and American spy submarines.

A Valiant bomber at 13,000 feet ( 3,962 m) dropped the first bomb on 15 May 1957. Many who witnessed the blast were astonished and terrified by its power. William Oates, a storeman on the island, recalled, ‘Probably the thing that scared me the most was not the ball of flame in the sky, not the searing heat but the blast and shock wave which followed later… I saw grown men at their wits end trying to run away from the blast.’

Operation Grapple ended in September 1958. Britain joined the USA and the USSR the next month in a moratorium on nuclear testing. Britain never tested in the open again, but Christmas Island was back in business by 1962 as a test site for the USA.

The moratorium had in fact collapsed when the Soviets began testing again in 1961. Britain lent its test site to the USA for a series of 25 tests called Operation Dominic, which was used to refine Polaris missiles. When Britain purchased the Polaris missiles from the USA, it effectively ended its own independent nuclear deterrent by becoming reliant on the USA for supply. In effect, this negated the original objective of Britain’s nuclear programme, which had been underway since the end of World War II.

-Russ Glackin first published in Issue 05 White Ensign

References:

- Blakeway Denys, Sue Lloyd-Roberts – Fields of Thunder: Testing Britain’s Bomb: London: Unwin 1985.

- Crawford, John, The involvement of Royal New Zealand Navy in the British Nuclear Testing programme of 1957 and 1958, Wellington: Headquarters New Zealand Defence Force, 1989. Ministry of Defence, Operation GRAPPLE.

- 1956-1957, London: HMSO, 1958.

- Wright, Gerry. We were There: Operation Grapple. New Plymouth: Zenith Publishing, n.d.