In the heart of the North Island HMNZS Irirangi, the Naval Radio Station was positioned strategically to communicate vital information to Admiralty and the New Zealand fleet. A combined services’ operation, the radio station also drew on the expertise of civilians.

Building a Radio Station

Why locate a radio station in Waiouru? The answer lies in the 1930s when research into radio transmission and reception was carried out in New Zealand.

It was found that there were two key factors required for an effective radio station to be established:

- the site had to be clear of urban areas likely to cause interference with the signal

- sufficient flat areas to construct the large aerial system required[1]

In 1941, the Navy’s Warrant Officer Biggs was sent to Waiouru to conduct assessment trials for the proposed station.

With the success of the trial, construction began in June 1942 for what was called the Combined Services Wireless Station.

Approximately 200 RNZN (consisting of 80 Wrens and 70 ratings) and RNZAF personnel would be stationed at the site.

The Receiver site covered nearly 100 hectares by itself. In order to avoid interference, the transmitter stations were located eleven kilometres north of the receivers at Waiouru.[2]

On 2 September 1942, WO Biggs was designated as the Commanding Officer of the unit. By the end of 1942, 70 ft (22 m) aerial masts, which had been stepped and rigged by the Lines Division of the Post & Telegraph, and four huts to contain transmitters; two for the Air Force and two for the Navy had been installed.

The huts were imaginatively christened AT1, AT2 for the RNZAF and NT1, NT2 for the Navy.

The installation of the equipment, fitting and testing to operational standard at NT1 and NR1 were the responsibility of the Post & Telegraph Radio Section. The team sent to Waiouru for this purpose was also to be available for any assistance requested by the RNZAF.

The P & T team at Waiouru comprised six of us plus occasional transient supervising engineers from Wellington. Those that stayed the distance were, A. Alderton, D. Calwell, G. Campbell, B. Fraser, H. Russell and Tom Seed.

The itinerant supervisors were J. Metcalfe, M. Parsons, G. Searle and E. Suckling.

About a dozen kilometres to the South, at Hihitahi, were two further huts for the receiving station buildings, land for their associated aerials and some accommodation.

These huts were named AR1 and NR1. Initially the RNZAF personnel had lived side-by-side with the RNZN staff, but later moved back to the camp at Waiouru.

Tent Town

For the P & T staff messing and accommodation was not with the Army but in tents in the Public Works Department’s camp, otherwise known as “Tent Town”.

Living conditions in general may be inferred from photographs. Looking back, with the exception of weekend leave, these were little short of those of prison camp conditions and ultimately had an unfortunate outcome for some of the residents. With at least one contracting tuberculosis.

There are several references to inspection visits by senior medical personal from both Services and their adverse reports supported complaints made by Servicemen.

National Wireless Telegraphy Service

At the beginning of 1943, the RNZAF station was in the charge of Flight Sergeant Tatton whose team worked largely independently in AT1, AT2 and AR1, transferring its signal station from Ohakea to Waiouru and consolidated there with the Navy to form the National Wireless Telegraphy centre.

The Transmitting station consisted of four sub stations.

There were two RNZNAF transmitters AT1 and AT2, and two RNZN transmitters NT3 and NT4.

Part of the equipment installed included an RCA AVT 22B broadcast transmitter. This transmitted Morse code at high speed often going across the world to stations such as the Bombay, India /Trincomalee, Ceylon circuits.

The bearing angle of the great circle between Waiouru and Bombay differs only slightly from that to Ceylon, so a single directional aerial could cover both countries.

In overall responsibility of Naval aspects of the station was Warrant Officer Biggs, and with some Ratings from Devonport he was busy at NT 2 with the RNZN2 and the RNZN3 transmitters which had been supplied by Devonport Dockyard.

The Public Works Dept. employees were the civilians. They had negligible contact with real civilians except for rare visits to Taihape because the operations of the station were kept as a close secret during the Second World War and outside contact was kept to an absolute minimum.

Later there appeared at NT2 a very low frequency transmitter and reputed to be for submarine communication.

How this would work from the middle of the North Island remains unclear. It wasn’t put into service during this time.

The two receiving centres, NR1 and AR1, constituted the operating heart of the station.

Associated with them were some rudimentary messing and accommodation facilities.

There were continuous but ineffectual attempts to improve domestic conditions. Waiouru can be a harsh landscape. The prime high speed receiving equipments were the two Marconi triple (spaced) diversity sets which worked on machine-sent signals at speeds up to a nominal 400 words per minute.

Combining the output from each receiver very effectively stopped the signals from fading. The anti-fade effectiveness of such an arrangement virtually eliminated dropped signals.

To effect much higher transmission speeds than hand-sent Morse mechanical means were used.

These consisted of the Creed Tape Perforators and Undulators. The basis of these machines was the use of reels of paper tape about 1½ cm wide which was dragged through the working parts of these devices.

From the key-board of the perforater holes were punched in the tape which corresponded to the symbols of the signal to be transmitted. When ready for transmission, the punched tape was passed at high speed through a mechanism which, through the holes in the tape, keyed the transmitter to send the corresponding symbol of the signal.

When such a signal was to be received it was far too fast for a human operator to copy and this function was performed by the Undulator which essentially consisted of a pen writing the received signal onto a similar tape whence it left a visual image of the Morse signal.

The machine-sent incoming high speed signals thus received into optically readable signals.

The tapes so produced were then laboriously translated to alpha-numeric typewriter or teleprinter symbols either at Waiouru or sent to Wellington according to priority and availability of operators.

On every watch thousands of code groups were received, relayed or transmitted.

War Service

During the war the Combined Services Wireless Station was the RNZN’s direct link with the Admiralty in London, naval bases in Canada, Bombay, East Africa, Australia, and the United States.

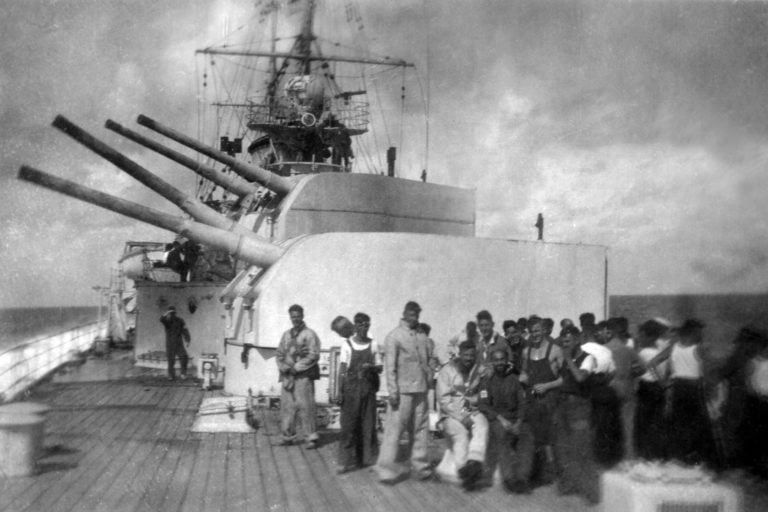

The Waiouru station also acted as part of the administrative signals network for the British Pacific Fleet (BPF) that operated in the Pacific from late 1944, until after the surrender of the Japanese in August 1945.

Part of this critical support was to sending Morse code signals for the Fleet Train to rendezvous with the fleet’s ships to conduct replenishments at sea.

Due to the overloading of the American fleets circuits when the Allied fleets were operating off Japan, Waiouru also handled the radio traffic for the BPF supporting the Admiralty in London in communicating with its ships.

At its wartime peak, the RNZN had 150 officers and ratings based at the station. This included over 80 women from the WRNZNS.

HMNZS Irrirangi

In June 1946, the RNZAF personnel were returned to Ohakea leaving behind their receivers and transmitters.

The station was renamed the Naval W/T Station Waiouru. AR1 was taken over in 1949 by the RNZN and renamed NR1.

During this time the station handled signal traffic to and from Naval Merchant vessels and to and from countries of the Commonwealth.

All the Wrens were sent to Wellington or Auckland at the end of the war.

On 30 October 1951, the Naval W/T Station Waiouru was commissioned as HMNZS Irrirangi. The Māori translation is ‘spirit voice’.

The badge was approved in February 1954, and the motto is Navibus et orbi (For the ships and to the world).[3]

By: Dr Tom Seed and Michael Wynd

[1] Naval W/T Station Waiouru 1942-1992, Privately Published: Auckland, 1992, p. 9

[2] ibid.

[3] Naval W/T Station Waiouru 1942-1992, Privately Published: Auckland, 1992, p. 3.