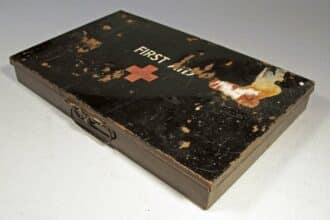

Medical personnel serve a vital role in all aspects of naval life and operations. Working on ships, shore-based hospitals, and other facilities, Medical Officers and Ratings have responsibilities ranging from emergency medical care to ensuring the general health of fellow sailors. The National Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy has a large and diverse collection of medical equipment spanning from the 1930s to the modern era. This article focuses on first aid kits used during the Second World War and how medicine was practiced at sea during this period.

Many of the items in a Second World War first aid kit will be familiar to anyone who has done a modern first aid course. Wound dressings such as elastic bandages, triangle bandages, and gauze were compressed, and sterilised with instructions printed on the packaging. Safety pins were used to secure dressings.

Tourniquets were used to slow the bleeding of more serious wounds.

Tourniquets made of heavy material such as canvas or leather were secured and tightened using brass cranks such as the ones pictured here.

Wooden splints were available in a variety of sizes to secure fractured limbs.

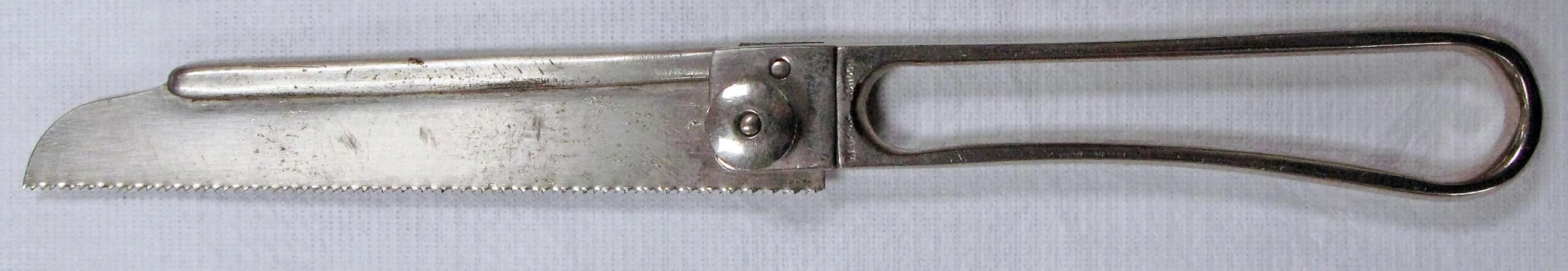

For wounds that required surgery, ships carried a variety of tools. These included simple surgical tools such as scalpels, tweezers, scissors, clasps, needles, and sutures. These tools would be used to remove the patient’s clothing, extract shrapnel, and to close wounds.

Rubber tubes and lubricant were available should a patient require intubation to assist breathing. In extreme cases, bone saws and rasps were also on hand should a major injury require amputation.

An interesting difference between sutures of this period and their modern equivalents is their material and storage. Silk sutures were stored in glass vials filled with an alcohol solution that would keep the sutures sterile and protected. Examples of these sutures can be seen in the Navy Museum’s Second World gallery.

One key difference between Second World War medical kits and modern examples is the type of pain relief, and anaesthetics and their ready availability. Anaesthesiology was not yet a specialist medical field and therefore the administration of anaesthetic drugs was typically assigned to junior doctors, sick berth ratings, or nurses.

In Britain and the wider Commonwealth, chloroform was the most commonly used anaesthetic. Chloroform capsules could be crushed into a handkerchief to produce fumes that would quickly render a patient insensible. The instructions printed on chloroform capsules warn against exceeding a dose of two capsules. Chloroform was generally considered a safe and effective anaesthetic by British physicians in this period. [1]

Morphine was also commonly used to relieve wounded sailors. In wartime first aid, morphine was often administered using a syrette; a disposable hypodermic needle connected to a dose of morphine contained in a squeezable package. Syrettes were used to administer a subdermal injection, meaning the drug was injected under the skin and left for the body to absorb. This would provide immediate relief from pain and shock.

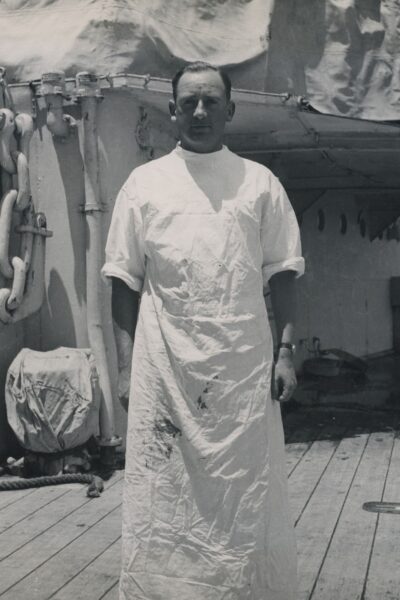

At the beginning of the Second World War, most cruisers had a complement of two medical officers and between three and six sick berth ratings. Medical officers were qualified physicians, while sick berth ratings would fulfil duties equivalent to those performed by junior doctors, nurses, and orderlies in land-based medical establishments. As the war went on, medical staff complements increased to three medical officers and six sick berth ratings. The higher complement ensured full medical staffing was available across the ship in the event of casualties caused by battle or accidental damage. However, a full medical complement was not expected to be required full time and both officers and ratings fulfilled other roles aboard their ship. [2]

In addition to first aid equipment such as that detailed above, ships were equipped with an x-ray machine and a basic laboratory. One major challenge for medicine at sea was stowage for medical supplies and refrigeration for any perishable medicines. Complex surgery and long-term recovery were not practiced aboard ships; therefore, the primary goal of ship’s medicine was to stabilise the sick and wounded for transport to land based hospitals. [3]

Following the Battle of River Plate, HMS Achilles suffered four killed and nine wounded. Of the nine wounded, four were considered to be in severe condition. The wounded men were transferred to a naval hospital on the Falkland Islands for recovery. [4]

Click here to learn more about the Battle of the River Plate

In the years before the Second World War, the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy had endeavoured to build a reserve force of medical personnel who could be rapidly mobilised in the case of war. These reservists were made up of qualified medical practitioners who joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and passed the requirements to be considered fit for service at sea.

One of these men was Surgeon Lieutenant Cecil Pittar, RNZNVR, an Auckland-based eye specialist. On the 29th August 1939, Pittar joined HMS Achilles as the second medical officer at only two hours’ notice before Achilles left New Zealand for six months. Achilles’ senior medical officer, Surgeon Lieutenant Colin Hunter, RN, was also a New Zealander. [5]

Like most New Zealand Navy medical reservists, Pittar served through the remainder of the war. Following the six months that Pittar served aboard HMS Achilles, which included the Battle of River Plate, Pittar was then transferred to England where he would serve on land in hospitals and continue his specialist practise in eye surgery for the Royal Navy.

Naval warfare in this period was known for being particularly deadly. Over the course of the Second World War, 672 New Zealand sailors lost their lives, of whom 494 were listed as killed during enemy action. This number includes the 150 New Zealanders who lost their lives in the sinking of HMS Neptune. This can be compared to the 762 New Zealanders who were invalided from the Navy, of whom 75 were invalided by wounds suffered in enemy action and sickness, accounting for the vast majority of cases. The medical officers and ratings of the Royal New Zealand Navy worked in extreme conditions without access to a fully equipped hospital at sea. Despite the extreme dangers they faced, many lives were saved by their efforts.

Written by Andrew Hart, Navy Museum Guide Host

References:

[1] J.A. Crowhurst, ‘The historical significance of anaesthesia events at Pearl Harbour’, Anaesth Intensive Care, 42, 2014, pp21-24.

[2] T. Stout and M. Duncan, Medical Services in New Zealand and the Pacific, Wellington, 1958i, p.170.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid, p.171.

[5] Ibid., pp.161-162.