New Zealand’s naval intelligence effort during the Second World War can be said to be characterised by a slow expansion of capabilities, building on the First World War experience. ‘Y’ intelligence certainly came into its own, as did the great expansion in inter-Allied co-operation.

Naval Intelligence Post WW1

At the beginning of World War I there was a tiny naval intelligence organisation in New Zealand, presided over by the Naval Intelligence Officer, Commander R.A. Newton, RN (Retired). Within two days of the outbreak of war, Newton had intercepted and begun translation of enemy messages. Naval intelligence in New Zealand was centred on signals intelligence with at least four radio stations attempting to intercept enemy traffic, and a local version of the Admiralty Reporting Officer system. The first work was provided by the crossing of the Pacific of Admiral von Spee’s Eastern Asiatic Squadron, which proceeded in a leisurely fashion through to the Battle of Coronel in November 1914. The British disaster at Coronel was reversed by the Battle of the Falkland Islands the following month. Between August and November, a considerable amount of monitoring of German signal traffic was done by the radio stations at Awarua, Awanui, Auckland and Wellington. During this time, Newton handed over his intelligence duties to Assistant Paymaster W.J.A. Brown, who seems to have remained as Naval Intelligence Officer for the rest of the war.

Along with the pattern of radio interception and the collection of intelligence through Reporting Officers, co-operation with naval intelligence authorities elsewhere, including the passing of intelligence back and forth, became a regular feature. This co-operation was not only with naval intelligence in Australia, but also was linked to the China Station in Hong Kong and (telegraphed via Hong Kong) naval intelligence in Ottawa. The pattern thus established continued throughout the duration of hostilities, though at less of a pace with the destruction of von Spee’s cruiser squadron. Isolated German raiders like the Wolf became the objects of attention later, but posed less of a threat to New Zealand’s merchant shipping.

After World War I, on 5 September 1921, Captain Moritz Yeo, RMLI, was appointed as District Naval Intelligence Officer in Wellington. He was succeeded just over a year later by Paymaster Lieutenant Commander J.T.V. Webster DSO, RN, in 1922.

In June 1925 the Admiralty enquired via the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs as to whether the New Zealand Government was prepared to assume responsibility for a naval intelligence centre in New Zealand, arrangements having been made along those lines in both Canada and Australia. The Commodore Commanding the New Zealand Station advised that the Admiralty’s recommendation be adopted, but the New Zealand Cabinet demurred, preferring to leave the decision to the incoming Government following the General Election.

In the meantime, Lieutenant Commander F. Lumb succeeded Webster as Staff Officer (Intelligence) in February 1926.

In June, the Admiralty enquired as to whether the time had come for the New Zealand Government to consider the possibility for the loan of a Royal Navy officer to join the staff of the Commodore Commanding New Zealand Station as Staff Officer (Operations). The New Zealand Government once again delayed any move for some months. In March 1927, the CCNZ noted in a memorandum that there did not seem to be enough work for a full time intelligence officer on the Station in peacetime, nor for a full time operations officer. Observing that in wartime, a Staff Officer (Intelligence) would have to look after a wide variety of operational and intelligence duties, including convoy organisation, liaison with both the army and the merchant marine, contraband control, local defence questions and other matters, he wondered if it would be useful to create a combined post of Staff Officer (Operations and Intelligence) who would work on either the flagship or at the Navy Office as required.

On 23 April 1927, the New Zealand Government indicated to the Admiralty that it would accept responsibility for the Naval Intelligence Centre, Wellington, as from 1 April 1928, provided that a Royal Navy officer could be loaned as Staff Officer (Operations and Intelligence) for a period of three years. The Admiralty replied in August that they had no objections to operational duties being undertaken by the Staff Officer (Intelligence) in peacetime, so long as these did not interfere with his primary duties as an intelligence officer. The Manual of Naval Intelligence was quoted in stressing the importance of the SO(I)’s being able to visit the Reporting Officers in their areas, and noted that local commanders should arrange their cruises to enable intelligence officers to carry this out. The Admiralty thought the title should remain as Staff Officer (Intelligence), and that in time of strained relations or with the outbreak of hostilities, the SO(I) should be at his post ashore.

On 31 October 1927, the New Zealand Government indicated that the services of a Royal Navy officer as Staff Officer (Operations and Intelligence) would be acceptable, and Lieutenant Commander C.J.M. Lange RN took over under the new arrangements as SO(O&I) on 3 April 1928. He was followed in this post by Lieutenant Commander W.H. Bremner DSO, DSC, RN on 15 August 1930, who in turn was succeeded by Lieutenant Commander G.St.A. Alcock RN on 10 February 1933.

The organisation

What sort of intelligence organisation did the naval intelligence officers preside over during this period? There was a system of Reporting Officers in New Zealand and across the South Pacific. In New Zealand, the Reporting Officers were the Collectors of Customs at Auckland, Napier, Wellington, Lyttelton, Dunedin, Bluff and the Postmaster on the Chatham Islands. Beyond these were the Reporting Officers at Suva in Fiji, Nuku’alofa in Tonga, Apia in Samoa, Rarotonga in the Cooks, Ocean Island, Fanning Island, Papeete in Tahiti, and Honolulu in Hawaii. The regular passage by vessels on the New Zealand Station allowed visits by the SO(O&I) from Wellington.

In November 1934, the Admiralty appointed Captain Shaw to the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, China Station, with the title of Captain on the Intelligence Staff (or Chief of the Intelligence Staff, sometimes simply known as the Captain on the Staff), located at first in Hong Kong. The objective was to centralise all naval intelligence in the Far East and deal with it as a comprehensive whole. This would become the Far East Combined Bureau (FECB), which in time would have important consequences for the future of intelligence operations in East Asia and the Pacific.

Thus it was that the Naval Intelligence Officers on the East Indies Station and the South American Division of the North American and West Indies Station, as well as the naval intelligence officers of Canada, Australia and New Zealand would have close links with the Captain on the Staff, FECB. In particular, in this regard, it should be noted that the New Zealand Naval Board agreed to co-operate with respect to intelligence on Japan’s intentions.

On 8 August 1935, Lieutenant Commander J.S. Head RN was appointed as SO(O&I) in Wellington. It was during Head’s time that the Admiralty requested, in late 1936, that there be an expansion of the number of high frequency direction-finding stations (H/F D/F) on shore around the world. A H/F D/F station at Awarua was established by the Post and Telegraph Department for civil aviation purposes, providing fixes for the trans-Tasman flying-boats. Its application for military purposes was to prove most useful, as early as 1938, which will be dealt with presently. A further station at Musick Point came into service in 1939 and two others followed later.

Lieutenant Commander T. Ellis RN took over as SO(O&I) on 4 February 1938. By April 1938, quite valuable monthly intelligence reports were being received from the Reporting Officers in Suva, Ocean Island, Nuku’alofa and elsewhere. Along with the developments in H/F D/F and ‘Y’ intelligence (to which we will turn shortly), the prospect of some over-arching intelligence organisation in New Zealand also began to come under consideration around this time.

In March 1939 the Director of Naval Intelligence at the Admiralty indicated an intention to explore close links with French intelligence elements abroad to do with operational intelligence affecting French and British naval units at sea. Ellis in Wellington was directed to explore this with the appropriate French officials in Papeete. On 3rd May, Ellis was given authority by the Admiralty to discuss measures with French intelligence officers for the protection of trade and naval deployments in the Pacific. An intelligence conference was held on 3 July on board the French sloop Dumont d’Urville, attended by Lieutenant Commander Ellis and Mr Ernest Edmonds (the latter being His Majesty’s Britannic Consul for French Oceania and Ellis’s Reporting Officer in Papeete), Captain Arzur of the Dumont d’Urville, and Lieutenant Commander Brachet, the Commandant de la Marine, French Oceania. While this conference turned out to be something of a waste of time, it at least underlined the fragility of the French position in the South Pacific. There seemed to be no direct communication between Noumea, the New Hebrides and Papeete, with no French naval reporting officers at the first two locations. The sloop Dumont d’Urville was the only sea-going French warship in the South Pacific. Brachet, the only French intelligence officer in the French Pacific possessions could contact the ship only at certain times, and then not in cypher. Intelligence reporting to Brachet was by native masters of trading schooners via the harbourmasters at Makatea Island or Papeete. Thus the idea of rapid reporting of operational intelligence was not going to get of the ground.

The Munich crisis of 1938 had given the H/F D/F station at Awarua the opportunity to work on the positions of German naval units at sea, a useful rehearsal for war and one for which Awarua was duly complemented. Late the following year, this would prove most valuable. We will return to signals intelligence later.

The position of the SO(O&I) itself became complicated, in August 1939 of all times, with the recall of Ellis to the Naval Intelligence Division in London, because of a shortage of intelligence officers. The folly of amalgamating intelligence and operations under one officer now compounded. Lieutenant Commander E.K.H. St.Aubyn DSC, RN, had arrived in New Zealand in July to take over as Staff Officer (Operations) from Ellis. Now St.Aubyn had both operations and intelligence responsibilities as well as some others. With the lack of provision at Navy Office for technical officers, St.Aubyn rapidly became, in the words of the Official Historian, “Staff Officer (Everything)”! St.Aubyn was undoubtedly a highly talented officer, but it was inevitable that the great raft of duties impaired his intelligence tasks. St.Aubyn’s staff in September 1939 and for the next few months, consisted of just three officers: an Assistant Staff Officer (Operations), an Assistant Staff Officer (Intelligence) and a Merchant Shipping Officer.

The Reporting Officer system underwent immediate alteration. Naval officers took over the role of Reporting Officers from the Collectors of Customs at Auckland, Lyttelton and Port Chalmers, while at Napier and Bluff the Collectors of Customs remained as Reporting Officers. At other New Zealand ports, the local Collectors of Customs came under the Comptroller of Customs in Wellington for shipping control and intelligence duties.

To the north of New Zealand the Reporting Officer system functioned with varying degrees of success. The SO(I) had only been able in the early period of the war, to visit Suva and Nuku’alofa. Suva handled more Pacific islands traffic than other ports, which did make it a focal point for intelligence purposes, something that became even more critical in 1941. Both the Comptroller of Customs in Suva, Mr Martin, and H.M. Consul and Agent in Nuku’alofa, Mr Armstrong, seems to have had considerable ability in their intelligence roles.

By contrast, and not for the want of ability, the Reporting Officers in Honolulu and Papeete experienced difficulties in this early part of the war. H.M. Consul in Papeete experienced some frustrations as he attempted to keep abreast of French intentions in the Pacific.

As only Suva and Fanning Island had undersea cable communications with Wellington, the problem of conveying secret messages from the other six Reporting Officers using commercial W/T posed problems. The lack of even adequate mail facilities and the distances involved often prevented use of the post to pass messages. So long as there was no worry about time delay, the despatch of confidential books and documents was of less concern in more remote islands. Ocean Island, for instance, was visited every few weeks. On the other hand, Fanning Island was only visited by the United States cable ship the Dickenson which ran four times a year from Honolulu. Unless there was ‘a reliable British subject’ on board, H.M. Consul in Honolulu was unable to send confidential documents in that ship.

If the strain imposed on the small intelligence staff was quite severe because of the lack of personnel, in June 1940 matters became more complicated. Not only did the presence of an enemy raider in New Zealand waters become apparent, but St.Aubyn was posted by the Admiralty to become SO(I) on the China Station. He was temporarily replaced by the New Zealand Squadron Signals Officer, Lieutenant Commander E.A. Nicholson RN, until a retired naval officer, Commander G.F. Hannay RN arrived from England in August.

Under Commander Hannay as SO(O&I), the operational and intelligence staff consisted of Lieutenant Commander Alderton RNZNVR as the Intelligence Officer, Lieutenant Commander Cornelius RNR as the Merchant Shipping Officer assisted by Lieutenant W.W.Brackenridge, along with two clerical assistants. Technical and material matters had been taken away from operations and intelligence.

Combining Ops and Intelligence

The question of combined intelligence had arisen well before the war, but it was not until September 1940 that a combined operations room and a combined intelligence centre were established. Part of the delay may be attributed to the Police Department’s input, which attempted in effect (in part unintentionally) to muddy the waters on matters of intelligence and internal security. Lack of Police co-operation and the establishment of the Security Intelligence Bureau in early 1940 had an impact on the Combined Intelligence Bureau which was formed. The Central War Room and the Combined Intelligence Bureau reflected the intelligence set-up under Hannay outlined above, with the addition of one, then two, RNZAF officers and an Army officer. The raider problem meant that the focus of the SO(O&I) was fully taken up with the routing of merchant shipping and day-to-day matters, so there was little time for intelligence work. There was, then, a large security emphasis in the widest sense of the term.

It quickly became apparent that the Merchant Shipping Section was inadequately staffed. Operational information was supplied to New Zealand naval and air force units by the Merchant Shipping Section and information collected was also exchanged between the naval authorities of adjacent stations and particularly the controlling authority for intelligence in the Pacific, the Far East Combined Bureau. Averages of 107 ships a day (including 35 coastal) were plotted during 1940, and this rose by a third in 1941. This did not include around 40 vessels per day (mostly foreign) that crossed to the north of New Zealand; these were not plotted as a result of lack of staff, resources and time. These figures did not include the positions of warships of all nationalities that needed to be located on the plot in the Central War Room. At this time, the equivalent section in Melbourne (which had not more than three times the number of ships to locate) had a Merchant Shipping staff of sixteen!

In November 1940 moves were undertaken to increase the number of watchkeepers with four new appointments to enable a twenty-four hour coverage.

Matters remained unsatisfactory however, and following urgent representations by the Chief of Naval Staff to the Admiralty, it was agreed that a new Staff Officer (Intelligence) should be appointed. Accordingly, Lieutenant Commander F.M. Beasley travelled to New Zealand in mid-1941. En-route, he visited the Far East Combined Bureau which had now moved to Singapore, and also the RAN’s naval intelligence set-up under the Director of Naval Intelligence, Commander Long. The views of both Hannay and Beasley regarding the shortcomings of the Combined Intelligence Bureau were taken into account, and Beasley arranged for the RAN DNI’s Civil Assistant, Walter Brooksbank, to come and assess the New Zealand CIB in September.

In the meantime, the Chief of Naval Staff had managed to push through the powerful Chiefs of Staff Committee approval for a total reorganisation of combined intelligence, although this did not finally obtain Cabinet approval until October 1941. Lack of staff, the lack of co-ordination of information from a variety of sources, the lack of adequate provision for the collation and assessment of operational intelligence necessary with the likelihood of the expansion of hostilities were matters to be addressed.

The new organisation that came into being was the Combined Operational Intelligence Centre under Beasley, who now had the title of Director of Naval Intelligence. The new Director was responsible to the three Chiefs of Staff, while also retaining command of naval intelligence in New Zealand.

The new COIC consisted of three departments: Section 1: the COIC; Section 2: General Intelligence; and Section 3: ‘Y’ Organisation and W/T Intelligence.

The COIC itself under the direction of the DNI consisted of a watchkeeping team of one Lieutenant and four watchkeepers, one Army officer, and one Air Force officer. It should be noted that increasing the number of watchkeepers was not approved until the onset of the war with Japan.

There were a number of specified functions which the COIC was to carry out. First, it was to collect, collate and analyse operational intelligence for the conduct of operations in the New Zealand area. There was to be an up-to-the-moment plot to be maintained of the overall situation, displayed for the Chiefs of Staff. Appreciations of the situation were to be prepared as required. Accessible organised detailed files were to be kept. Combined intelligence summaries were to be issued, and assessments made of New Zealand defence preparations. All naval operational intelligence was to be dealt with by the DNI.

The General Intelligence Section was commanded by Lieutenant Commander H.S. Barker RN (rtd). This was a security section, which focused on the security of wharves, dockyards, shipping, naval establishments, passes and permits, vital points, censorship liaison, suspected persons and general internal security. There needed to liaison with the Security Intelligence Bureau (particularly their Port Security organisation), the Police Department, the harbour authorities, the Army Field Security Sections and Air Force security. The New Zealand Naval War Diary was to be compiled by the Censorship Liaison Officer in Wellington, who could also stand in as a watchkeeper for the COIC (in fact the War Diary was written up in the COIC). There was a civilian liaison officer for the media (radio, press, cinema and other publicity) who also produced periodical intelligence summaries and occasional reports.

Section 3 was the ‘Y’ Organisation and W/T intelligence set-up. This was the centre of a small signals intelligence organisation under Lieutenant H. Philpott, which collated and analysed all the incoming signals intelligence. The H/F D/F stations and the later REB station came under his jurisdiction. The ‘Y’ Organisation in the early part of the war supplied intelligence to the Captain on the Staff at Far East Combined Bureau at Singapore (in early 1942 FECB was withdrawn to Colombo and Mombasa, following the Japanese occupation of Malaya). It also had close liaison with the RAN ‘Y’ set-up. The ‘Y’ Room supplied operational signals intelligence to Section 1, the COIC proper.

It should also be noted that naval intelligence officers were attached to each Area Headquarters in New Zealand, these being known as District Intelligence Officers, each of which ran a small combined intelligence section.

In December 1941 a SO(I) was appointed to the staff of the Naval Officer-in-Charge Suva, and a small Combined Intelligence Centre was formed from one officer from each service. The SO(I) in Suva was also involved in the operation of the islands’ coastwatching service.

Japanese entry into the war

With the entry of Japan into the war, a daily meeting now took place at 10 a.m. in the Central War Room, attended by the Chiefs of Staff and other officers concerned. The briefing officers of the COIC outlined the intelligence received over the last 24 hours and indicated last known positions of enemy and Allied forces. Following this meeting, a Daily Intelligence Summary was drawn up and issued shortly after midday. A précis of this was sent out by signal known as a ‘GENSIT’ [General Situation] to British and US authorities in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean.

A weekly summary of all intelligence known as the Combined Operational Intelligence Summary was compiled and issued by the COIC. This MOST SECRET summary went to Service addressees, including the RAN DNI, the US Commanders of the South Pacific, the South West Pacific, the US Pacific Fleet, the US Marine Corps, the Captain on the Intelligence Staff in Kilindi, and latterly the DNI at the Admiralty. At the end of 1943 this summary was reduced in size and became a fortnightly production.

A General Intelligence Summary was compiled fortnightly. This was a condensed survey which omitted the detail of the COIC Summary, and was designed for political and civilian authorities in New Zealand, plus the Governor of Fiji, the DNIs in Ottawa, Pretoria and Delhi, and sundry US authorities.

A periodical Summary of Defence Preparations was also put together, largely by naval intelligence.

In the first half of 1943 the COIC began to send out a series of signals known as ‘KIWIS’. These informed the DNI at the Admiralty, the C-in-C Eastern Fleet, GHQ in Delhi, the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board and the British Admiralty Delegation in Washington of all available intelligence in the New Zealand area.

It should be noted in passing that with the arrival of Japanese POWs in late 1942, a nucleus of an interrogation organisation was set up. This lapsed when the US forces in Noumea took over responsibility for this function, although not before an officer from COIC had prised out the new information that the Japanese battleship Yamato had 18-inch guns.

To go back a little, it needs to be noted that there had been alterations in the strategic areas designated by the Allies. First there was the ANZAC Area, then the SOUTH PACIFIC and SOUTH WEST PACIFIC areas. Intelligence from New Caledonia, the New Hebrides and Santa Cruz Islands now came to Wellington as well as Melbourne. On 7 February 1942 Vice Admiral Leary USN assumed command of the ANZAC Area with his headquarters in Melbourne. Beasley, the DNI, went to Melbourne and joined the staff of COMANZAC as New Zealand Liaison Officer, co-operating closely with the RAN and the US Navy. After two months, however, ANZAC Area ceased to exist, and Beasley returned to resume his duties as DNI in Wellington. When Vice Admiral Ghormley established his headquarters in Auckland, there was some discussion of moving the COIC there, but this came to nothing and the New Zealand and US intelligence organisations remained separate. It did lead to some US naval staff and the US Naval Attaché being accommodated at Navy Office in Wellington, and a good deal of close practical collaboration followed, with the COIC providing a large amount of intelligence on the South Pacific. When the US forces moved north, an officer from the COIC, Lieutenant Commander Brackenridge, was appointed as liaison officer to COMSOPAC in January 1943.

The Tech

Perhaps it is useful at this point to turn our attention to the source of intelligence, and first consider H/F D/F and REB.

The high frequency direction-finding stations of Awarua, Musick Point and Waipapakauri were most important, along with the Army’s intercept unit at Nairnville Park in Johnsonville for the interception of enemy signals traffic. Awarua, as has been noted, had a practice run in 1938 in locating German naval units at sea. In late 1939, three Canadian H/F D/F stations at St.Hubert, Shediac and Botwood, a station in Bombay, and Awarua tracked the progress of the Admiral Graf Spee across the South Atlantic prior to its interception, chase and destruction by Commodore Harwood’s cruisers at the Battle of the River Plate. Awarua was congratulated by the Admiralty for that work.

The German surface raider signal traffic when they were around New Zealand in 1940 and 1941 was an obvious target for the direction-finding stations, but good cypher security plus careful use of wireless silence seems to have provided relative immunity. There is no doubt that the New Zealand H/F D/F stations continued to pick up a fair amount of U-boat traffic in the Atlantic during the war.

In Fiji, the establishment of an H/F D/F station run by New Zealand naval personnel at Tamavua took place in part because the RN staff for this station had been torpedoed en route. The D/F stations were set up in 1941 and were under the operational control of the FECB in Singapore. Part of the responsibility for this station, and for other stations, was to monitor the Japanese radio traffic in the Mandated Islands under Japanese jurisdiction. This was done with considerable success, with a large rise in Japanese signal traffic in the days leading up to Pearl Harbour and the great sweep south in East Asia.

The relocation of FECB after the fall of Singapore brought about a reorganisation in the provision of direction-finding product. The RNZN stations now provided a good deal of service to a huge Allied direction-finding and radio intercept operation that included British, Australian, Canadian and American intelligence authorities.

Direction-finding was important because it was one of the few ways of establishing the general location of enemy units at sea beyond the range of aerial reconnaissance or from direct sighting reports from ships. The World War I experience needs to be remembered here, for in 1939 there was an established pattern to follow. Moreover, with regard to the use of P&T Department personnel, some of those had had experience in the first war. ‘Hec’ Head had been involved in signals interception work in that war; in World War II he was Superintendent of Awarua Radio.

In summary, the following things may be briefly said about the signals intelligence achievements. The New Zealand stations D/F’d the Japanese submarines both before and after the Sydney Harbour raid, although no notice of the warnings seems to have been taken. However, the RAN took more notice and indeed made considerable use of the New Zealand direction-finding product after this, as did the US Navy.

The direction-finding organisation was expanded in 1942 and the plotting centre well established at Navy Office. Bearings were received from all over the place by New Zealand, Australian, US and Canadian stations. The New Zealand organisation later took over the plotting of all D/F bearings for the US COMSOPAC. Between 300 and 400 bearings were received daily and a signal was sent out summarising the results of these fixes. There was, then close D/F and Y co-operation between Melbourne, Kilindi, Colombo, Ottawa and Honolulu, not to mention further afield in both the US and UK. D/F co-operation between Pearl Harbour, Melbourne and Wellington was carried out by W/T transmission direct to and from all H/F D/F stations, comprising a network of about 18 stations. Fixes were promulgated by Pearl Harbour W/T stations including appropriate bearings to Wellington. Wellington was responsible for informing the Commander US 3rd Fleet and the ACNB of fixes on local transmissions not heard by Pearl Harbour.

M/F D/F stations were established at Awarua, Auckland, Blenheim, Napier and Suva for D/F bearings on distress transmissions from Allied shipping.

A radio-fingerprinting unit was established at an isolated farmhouse on Wratts Road outside Blenheim at the end of 1942 and commenced operating in January 1943. It was linked in to the New Zealand direction-finding network and passed the product of its work to the ‘Y’ Room at Navy Office. The task was the identification of enemy units by transmitter signature using specialised equipment known as Radio Fingerprinting (RFP). This was highly secret work and an integral part of British and American signals intelligence efforts against enemy naval units. D/F and RFP combined to locate and identify enemy naval units at sea. The ‘Blenheim W/T Station’ (its official title) was responsible in part for causing discomfort to a number of Japanese submarine commanders through 1943 and up to May 1944 when the station closed.

All this signals intelligence effort was co-ordinated by a small analytical team under Philpott at Navy Office, and made a very useful contribution operationally to the Allied signals intelligence effort. Philpott closely controlled the D/F and RFP intercept operations, the product going to both COIC and elsewhere. The ‘Y’ Room at Navy Office was responsible for the handling of ULTRA signals intelligence material passed on from Australian, British and American authorities, as well as contributing in a small way to that great effort.

Coastwatching

Coastwatching was another source of intelligence with a long history. For World War II plans were made at various times for a network of coastwatching stations around the New Zealand coast. The first plan was in 1929, with a series of revisions in 1935 and 1937 to 1939. By March 1940 some 62 stations had been established. This included 3 Port War Signal Stations, one coastal battery observation post, 18 lighthouses, 18 stations manned by Harbour Board staff and 22 stations manned by military reservists mostly in inaccessible places.

It is worth noting that some areas were covered by periodic surveillance flights, either military or commercial, e.g. the 200 mile stretch of coast between Jackson’s Bay and Puysegur Point. There were some closures of stations in 1940 which were hurriedly reversed with the advent of the activities of German armed merchant raiders in New Zealand waters and across the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The war with Japan saw more stations open so that over 60 were operational. In March-April 1942 stations were opened on Campbell Island and the Auckland Islands, and in July on the Chathams.

During 1943 with the improvement of the fortunes of the war, the War Cabinet decided to reduce the number of stations, and of 76 then in existence, 17 were abandoned, 13 were reduced to maintenance only, with around 30 still in full operation.

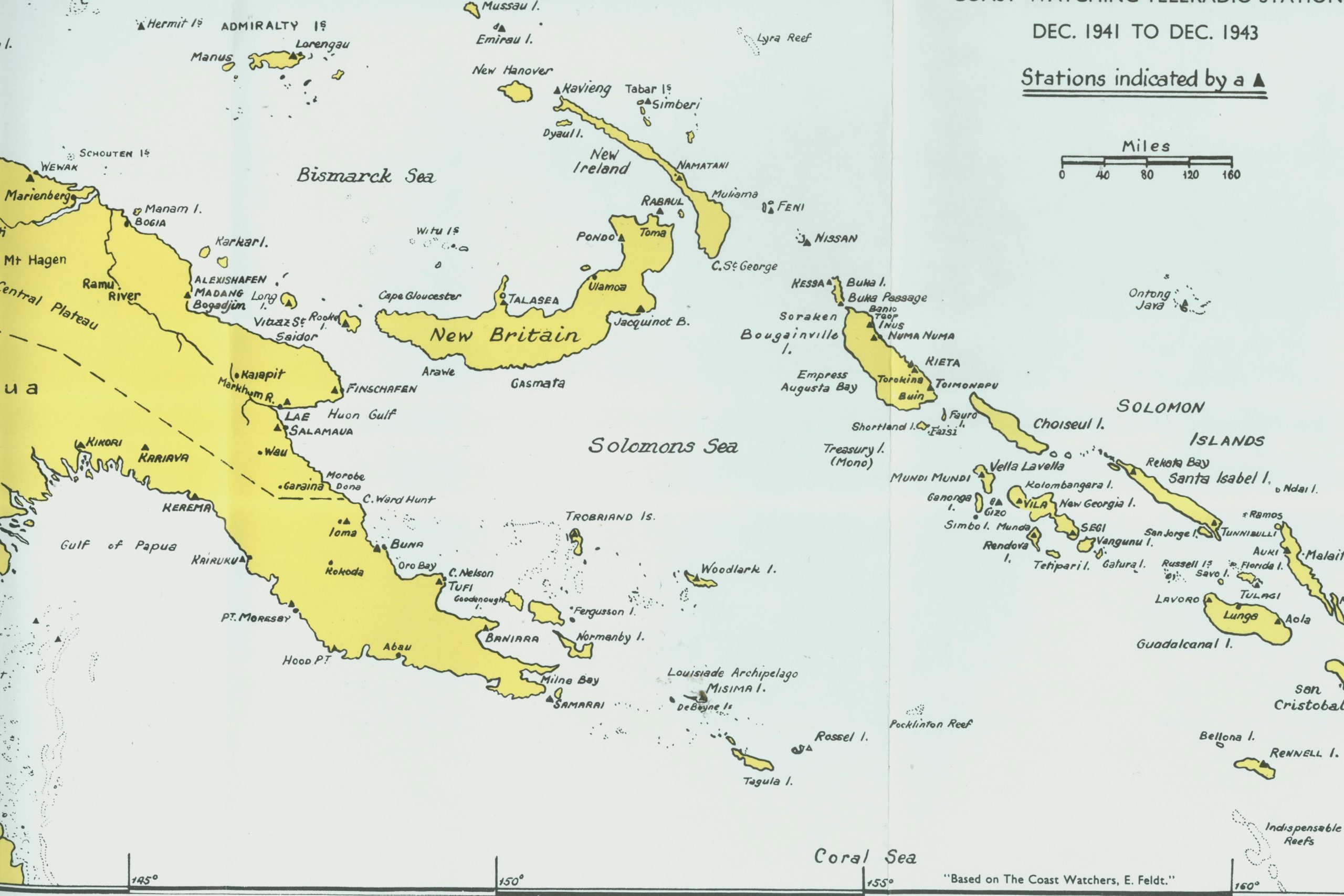

Coastwatching in the Pacific Islands was initiated in Suva by the Commodore Commanding New Zealand Station in July 1939, although very little was achieved in concrete terms until October 1940. Eventually some 78 stations would be established, with the priority accorded to the posts in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands closest to the Japanese Mandated Islands. Mr Steel, the Controller of Pacific Communications in Suva, was most important in the establishment of New Zealand’s overseas coastwatching effort. The outlying stations were connected by teleradio and use was made of the Playfair code in communication. The coastwatching stations like the Australian effort in the Solomons and elsewhere proved its worth. There is no doubt that coastwatching intelligence was sometimes used as a cover for ULTRA intelligence.

The onset of hostilities brought with it the capture of the northern Gilberts by the Japanese. The first coastwatchers were taken prisoner and held in Japan. The second phase of the Japanese occupation of the Gilberts resulted in the capture and execution of 17 coastwatching staff plus 5 other Europeans in October 1942.

During 1943, with the turn of the tide in the Allies favour, there was a reduction in the New Zealand intelligence effort overall, although it needs to be noted in passing that RNZAF intelligence expanded considerably with the forward presence of No.1 Islands Group. The reduction in effort was seen with the end of 24 hour watchkeeping in the Central War Room and COIC. One officer was on day duty, with others on a part time basis. Matters of urgency could be dealt with overnight by the Merchant Shipping Office staff under the direction of the duty staff officer. The naval section of COIC however continued to work of purely naval intelligence. Not only signals intelligence, but the study of POW interrogation reports, enemy documents and other reports went into the production of New Zealand Naval Intelligence Memoranda. The submarine situation around New Zealand was of primary importance, and the production of a daily chart and monthly summary of submarine activities was a priority. The Air Force section of the COIC had been considerably enlarged in 1943, and moved to become a separate department outside the COIC. The Army withdrew its liaison officer during this period. The daily staff meeting in the COIC was also reduced to three meetings per week.

By October-November 1944 the combined intelligence organisation had been reduced to the DNI with two intelligence sections. There were now two officers and two WRENS, a Historical Section of one civilian (S.D. Waters), and a security section of one officer. However, the establishment and expansion of the Waiouru W/T Station ran somewhat counter to this, for while the head of the intelligence organisation was shrinking, the capabilities of the ‘Y’ organisation was transforming and in some areas expanding.

In conclusion, New Zealand’s naval intelligence effort during the Second World War can be said to be characterised by a slow expansion of capabilities, building on the First World War experience. ‘Y’ intelligence certainly came into its own, as did the great expansion in inter-Allied co-operation. The New Zealand intelligence effort was not part of some intelligence monolith, but was a small yet significant component of an evolving intelligence effort. There were some achievements and some weaknesses. The lack of a single DNI for the duration of war and the slowness in sorting out the combined intelligence organisation was clearly a major deficiency, when events and operational urgency finally precipitated action. The slenderness of intelligence resources, the fact that daily intelligence reports were not produced until after the opening of hostilities with Japan were glaring faults. Balancing that were the achievements in signals intelligence and the useful work in an inter-Allied context from an operational perspective, which included an input into a broader intelligence picture. Naval intelligence probably suffered from being closed off too early; nevertheless it made a very useful contribution to the war, and developed a further raft of experience as its legacy, in much the same way as the effort in the First World War.