Read about HMS Achilles and her role in escort duties, Force G including information about Captain Parry and Commander Harwood.

The Admiralty declared an ‘emergency situation’ on 23 August 1939. The ‘Preparatory Telegram’ was sent informing British and Dominion ships and naval commands world-wide that war was imminent. The next day, the Alert Telegram was received. In Auckland, HMS Achilles was docked, cleaned, had her underwater hull painted and then loaded full war stores at Devonport, Auckland.[1]

The Admiralty was telegraphed on the 28th August that Achilles was war-ready. The next morning the Admiralty instructed her to sail to her war station, to be under the command of the Commodore, America and West Indies Station. ACHILLES sailed for Balboa and the Panama Canal that day, less than six hours after receiving her sailing orders.

On 3 September at 11.00 am (in London), Britain’s ultimatum to Germany expired and the Admiralty telegram, ‘Commence hostilities against Germany’ was sent. Shortly afterwards in New Zealand the Prime Ministers Department confirmed the decision to the New Zealand Naval Board.[2] The Division was at war.

Blockade and Escort Duties

At sea when war broke out, Achilles was ordered to divert to Valparaiso, Chile, arriving there to refuel on 12 September. The strategy of blockade was as old as naval warfare, so when war was declared against Nazi Germany, the Admiralty instituted a blockade world-wide. Achilles thus bore the brunt of blockade duties on South America’s west coast. In Valparaiso she received new orders to patrol the Pacific Coast of South America in search of German shipping.

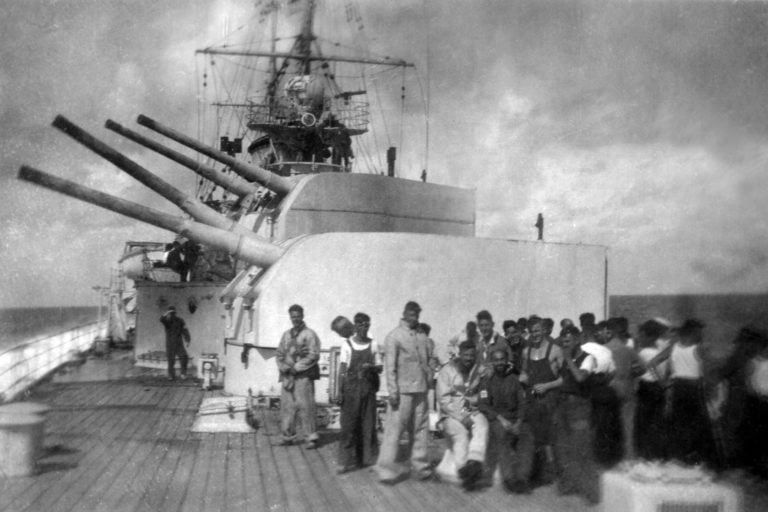

During her brief stay in the port, as a combatant in a neutral country, she could only stay for one day. None-the-less the formal courtesies were exchanged: “ACHILLES…saluted the Chile with 21 guns, and the Admiral’s flag flying from the battleship Chile’s ADMIRAL LATORRE with 13 guns. Both salutes were returned.”[3]

Two German merchant ships were in the port at the time but they could not be seized by the Royal Navy as they were in neutral territory. Captain Parry, after conferring with the British Naval Attaché in Valparaiso, summarized his view on the ship’s mission:

Various German merchant ships then sheltering in ports on the west coast of South America were capable of being armed and were therefore a potential threat to our trade. The more active at the moment were those in Peruvian waters, which were endeavouring to obtain supplies of fuel-oil.

The Naval Attaché considered that the presence of HMNZS [sic][4] ACHILLES would be reported at once along the coast and might induce these ships to intern themselves.”[5]

Over a six-week period she searched the area, calling at sixteen ports and anchorages, the most northerly Buenaventura in Colombia, to the most southerly Puerto Montt in Chile. During this time a number of German ships were encountered, all within neutral waters, and thus could not be seized. The sight of the cruiser along the South American Pacific coast however had the desired effect, as only a few German ships put to sea and a large number interned themselves for the duration of the war.

The South American navies were impressed with both the conduct of the cruiser and her Captain: “Captain Parry later heard from the Naval Attaché [in Valparaiso] that the . . . authorities were impressed with Achilles’ strict observance of their neutrality laws in sailing within 24 hours after . . . a busy day in harbour.”[6]

During the time off the west coast of South America, Achilles also escorted several British-flagged merchant ships. The Naval Staff Narrative summarised this period:

Yet the mere presence of the ACHILLES in South American waters was sufficient to keep German trade at a standstill and virtually to immobilise some 17 enemy merchant ships totalling 84,000 tons in neutral ports from the Panama Canal to the Strait of Magellan, along a coastline of 5,000 miles.[7]

Achilles then sailed around the Horn for the Falkland Islands, arriving there on 22 October. Arriving at Port Stanley no time was wasted in refuelling and re-provisioning the ship. However, “opportunity was taken to give as much shore leave as possible”. Efforts were made to accommodate the crew: “the 22nd being a Sunday, special arrangements were made to open the public houses, but local opinion would not tolerate a cinema performance”.[8]

Force G

Achilles sailed the next day for the Rio Del Plata area, to rendezvous with ships of the South Atlantic Division, under the command of Commodore Henry Harwood RN. His force when at sea was also known as Force G (one of several task forces formed to hunt for enemy raiders). This division initially comprised two cruisers HMS Ajax (8 x 6-inch guns) a sister ship to Achilles, and HMS Exeter (6 x 8-inch guns). The two cruisers had been operating in the area since the war’s outbreak. Exeter left the division for a short time to escort British shipping, while Ajax intercepted and sank two German merchant ships.[9] Shortly afterwards Force G was further reinforced by the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland (8 x 8-inch guns) and two destroyers, HMS Havock and Hotspur. For over a month this formation patrolled the area concentrating between Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and River Plate. Their dual role was to protect British shipping in the area as well as intercepting German merchant ships and searching for enemy warships.

One major problem facing Commodore Harwood was the supply of stores and fuel, considering the vast sea area he had to cover. The Naval Staff Narrative notes:

They were operating off the neutral coasts of Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, which fringed the Atlantic for 3,000 miles. His nearest British base, the Falkland Islands, was 1,000 miles to the southward of the River Plate and the selection of suitable anchorages for refuelling was a difficult matter.[10]

He was further restricted in that the only two British Fleet Auxiliary tankers in the area RFA Olwyn and Olynthus were ‘station tankers’[11], to refuel, the cruisers had to raft alongside the tanker in a sheltered anchorage. At that stage of the war the Royal Navy had not developed the equipment to refuel underway at sea.

Nine Ships Sunk

With the outbreak of war all three German ‘pocket battleships’ (Panzerschiff)[12] had began to operate against British merchant shipping. One of these, the KMS Admiral Graf Spee had the South Atlantic as her intended operating area. Spee had sailed on 21st August from Wilhelmshaven, reaching the South Atlantic (via the North Sea, Greenland Sea and North Atlantic) on 26 September. During this time her orders were not to attack any shipping but to conceal herself. Spee commenced her attacks upon arrival. Between sinking her first victim on 30th September and her last on 7th December, she accounted for nine ships. Operating far and wide in the South Atlantic, Spee even ventured for a short period into the Indian Ocean.

On 2 October, the Admiralty in London informed Harwood that his force would be reinforced by Achilles. In the meantime Harwood had shifted his flag to Ajax, and in company with the destroyers, provided escorts for British shipping in the area, while the two 8-inch cruisers were detached, serving as an independent hunting group. On 20 October, the destroyers were ordered away to the West Indies and Harwood then awaited Achilles’ arrival in the area.

Achilles sighted Exeter, again Harwood’s flagship, early on the morning of 26 October off the River Plate. They joined up with Cumberland on the 27th, and that day, Harwood again transferred his flag to Ajax, while Exeter left for the Falkland Islands to undertake minor repairs. The three cruisers operated together, but Harwood ordered Cumberland into Buenos Aires to refuel, leaving just the two 6-inch ships at sea. Exeter had sailed from the Falklands on the 4th and rejoining the force, when Harwood again split his force up, with the two 8-inch armed ships operating together.

Ajax and Achilles operated independently, the former patrolling the River Plate area, and the latter further along the Atlantic coast. From the 7th to the 16th, Achilles operated independently in a similar way to her original deployment off the Pacific coast—a combination of port visits while searching for German ships. Achilles entered Rio de Janeiro on the 10th, saluting the Brazilian flag flying from Fort Villegagon.

Captain Parry

Captain Parry made a number of official calls including: the British Ambassador,[13] the British Consul, the Brazilian Minister of Marine, Chief of Naval Staff, and Senior Naval Officer Afloat and Parry and his ship’s officers had cocktails with the ambassador that night. Despite at war the requirements of Defence Diplomacy still had to be met. Leave was granted and as Captain Parry noted in a press release it was a ‘most popular city and there were no leave breakers’.[14] There was, however, one glitch: “two men broke out of the ship in the motor skiff during the night and missed the ship next morning. They were arrested.”[15]

Leaving on the 12th, the Brazilian admiral’s flag, flying from the battleship Sao Paulo, was saluted with fifteen guns. Achilles proceeded to patrol the shipping lanes off the coast until the 22nd when she met up with Ajax off the River Plate, sailing separately later that day to San Borombon Bay to refuel and take in three months of provisions from Olynthus, with Achilles sailing late that night, under orders to show herself off Brazilian ports.

This she did, sometimes too close for Brazilian comfort. While approaching Rio Grande de Sol, a Brazilian military aircraft overflew her, later; a formal complaint was made by the Brazilian Chief of Naval Staff about her movements off the harbour.[16]

On 4 December Achilles was ordered south to refuel at Montevideo, arriving there on the 8th. During her solo mission she encountered many ships, indicating the amount of sea traffic on the South American sea routes: ‘Achilles had sighted at sea 58 ships of foreign nationality – United States, French, Belgian, Norwegian, Danish, Dutch, Swedish, Greek, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Brazilian, Argentinean, and Panamanian – as well as many British merchant ships.’[17]

A list of defects was provided to justify her stay in the port over the normal one day limit. Captain Parry made no official calls during the stay but leave was granted to the ship’s company. Charabanc (bus) tours, dances and suppers, visits to sports events, were all arranged and again there was good behaviour and no leave breaking.[18]

Commodore Harwood

Achilles sailed late on the 9th to rendezvous with Harwood off the River Plate where he had decided to concentrate his force. Achilles joined Ajax the next day and they were joined by Exeter on the 12th.[19] Commodore Harwood believed the German raider was heading to the River Plate area, as he later wrote:

I decided that the Plate [sic], with its larger number of ships and its very valuable grain and meat trade, was the vital area to be defended. I therefore arranged to concentrate there my available forces in advance of the time it was anticipated the raider might start operations in that area.[20]

Harwood’s intelligence was probably a summary of the positions reported by the various merchant ships taken by the Spee. Each British ship was required to transmit a raider report if sighted and attacked by the enemy – even at the cost of the shell fire the radio transmissions would bring. Harwood was correct; on the morning of 13 December, the South Atlantic Division, HM Ships Ajax (Harwood’s flagship) Achilles and Exeter, intercepted the Admiral Graf Spee some 200 nautical miles off the estuary of the Rio Del Plata. The Battle of the River Plate had begun.

References

Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO c1946/1947.

E.J. Grove, Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

W.D. McIntyre, New Zealand Prepares for War, Christchurch: University of Canterbury Press, 1988.

S.D. Waters, The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956

[1] This meant three months’ supplies and filling the magazines to full capacity. Normally, only one month’s supplies would be carried, and the magazines would be half filled.

[2] S.D. Waters, The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956, p.18.

[3] Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO c1946/1947, p. 3.

[4] Captain Parry’s Report of Proceedings was written in January/February 1940, the Naval Staff Narrative not until 1946 or 1947. the ship’s prefix was HMS not HMNZS in December 1939.

[5] Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO, n.d., p. 4. Quote from HMS Achilles Report of Proceedings.

[6] ibid., p.5. Quote from HMS Achilles Report of Proceedings.

[7] ibid., p.16.

[8] ibid., p. 25.

[9] Normal practice was to put a prize crew on the ships and then sail them to a British port, but Ajax was unable to spare the men, so the ships were sunk and their crews taken aboard the cruiser.

[10] Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO, n.d., p. 22. Remember, though Harwood could refuel in neutral territory, as a belligerent his stay was limited to a maximum of 24-hours, and even then he was restricted to only enough fuel to reach the nearest port of a neighbouring state

[11] Station Tankers: Tankers assigned to the South Atlantic Station. Re-fuelling had to be done in a safe harbour.

[12] These were the so-called ‘pocket battleships’ in the British press. This was never an official designation; the Germans themselves referred to them as Panzerschiff – literally in English, armoured ship – which was the exact description of the replacement ships allowed Germany as printed in the German language copy of the Versailles Treaty of 1919. Incidentally, the Germans’ re-rated the two survivors, SCHEER and DEUTSCHLAND renamed LUTZOW, as heavy cruiser in 1940.

[13] Rio de Janeiro at this time was the national capital.

[14] Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO n.d., p. 56. ‘We paid a very pleasant 48-hour visit . . . we did our Christmas shopping; we danced and lost money in the casinos; and we played golf in ideal surroundings.’ Leave breakers were those sailors who were late back to the ship.

[15] ibid., p. 56.

[16] ibid., p. 59.

[17] ibid., p. 60. Quote from Parry’s Report of Proceedings.

[18] ibid., p. 61.

[19] Cumberland, was at the Falkland Islands completing a self-refit to remedy urgent mechanical deficiencies, but could sail at twenty four hours notice, with two engines ready at any one time.

[20] Admiralty, Naval Staff Narrative; Operations of HMS Achilles, August 1939 – February 1940, London: HMSO n.d., p. 71. Quote from Battle of the River Plate, Report of Rear-Admiral Commanding South American Division.

![Amokura Training Ship Amokura [formerly HMS Sparrow]](https://navymuseum.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/amokura.jpg)