At the outbreak of the Second World War, Malta was the only base in the Mediterranean for the British forces. Read about New Zealand and the Malta Convoys.

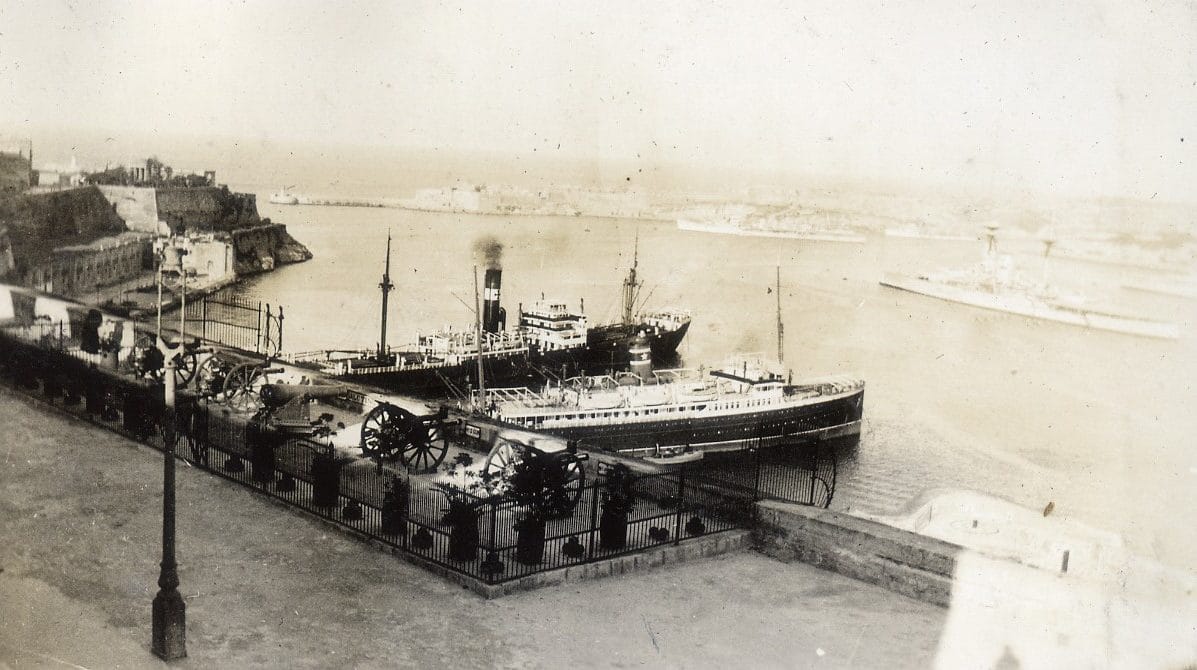

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Malta was the only base in the Mediterranean for the British forces. Malta consisted of two islands, Malta and the small island of Gozo. Valletta was the harbour and base for the RN. The civilian population was 275,000 living in 300 sq.km of space. The land was capable of feeding one-third of the population but Malta, which had depended for its existence on peacetime service establishments, was virtually unproductive, and stocks of food and all war material had to come by sea. Above all, petrol, the bugbear of every Mediterranean commander, was at a premium. By 1940 the island was supplied from Alexandria via the Suez Canal. The defences at June 1940 consisted of anti-aircraft guns, a RAF squadron, and some flying boats.[1] The Royal Navy maintained a fleet of submarines at Malta throughout the air campaign.[2] The air defences were manned by a mixture of Army, RAF and RN personnel. Fleet Air Arm aircraft flew combat air patrols from Malta supporting the RAF.

From 1939 to December 1940 it was generally free from attack by the German & then Italian forces when Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940. Malta was vulnerable to an air campaign, being only 97kms [60miles] from Sicily, well within the range of Italian aircraft. From June 1940 Malta was vital to the Allied operations against the Italian supply route to its forces in North Africa. On 9 July 1940 a British force escorting a convoy from Malta to Alexandria engaged an Italian convoy bound for North Africa. The outcome was inconclusive.[3] The RN was hampered in defeating the Italian fleet by the need to escort convoys to and from Malta. When the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious arrived, the RN launched the attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto on 11 November 1940. For the loss of two Swordfish torpedo bombers, half of the Italian fleet was crippled. It was a major setback to the Italian navy and ensured that any Aix effort against Malta would be by air attacks.[4] With the reverses in North Africa and at sea Mussolini asked for German air support. In January 1941 German fighters and bombers arrived in Italian airfields in southern Italy and Sicily.[5]

The Axis air campaign against Malta began in January 1941 when Axis aircraft began attacking military targets. On 10 January 1941 the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious limped back into the Grand Harbour after being heavily hit, and the period which became known as the ‘Illustrious blitz’ had begun. This was led by the Luftwaffe and was largely opportunist and designed to bolster flagging Italian morale.[6] But Malta stood firm, as it had against the Italian Air Force. Its shipping offensive, however, practically ceased, while the Luftwaffe forced the re-routing of Middle East convoys around the Cape of Good Hope, thus impeding the supply of war material to the British forces in Greece and allowing the free running of Axis convoys to North Africa. This air campaign continued through to December 1942.

The February convoy had failed to get through to the island, but in March a combined operation by all services, which demanded a feint attack by the land forces in North Africa and strategic bombing by the Middle East Command of enemy airfields in Rhodes, Greece, and Crete, brought three merchant vessels through ‘Bomb Alley’ from Alexandria. But the Luftwaffe finally sank all three, and only 807 tons of cargo, including some oil, was salvaged. Middle East Command could not afford another convoy for April.[7] The beleaguered garrison received new heart on 20 April, when forty-seven Spitfires flew in from the United States aircraft-carrier USS Wasp. They had been despatched from the carrier by Wing-Commander J. S. McLean.[8]

The supply situation was still critical, since the passage of the Narrow Seas remained closed except to essential supplies of petrol and torpedoes which came in by submarine. In June a convoy of eleven ships was turned back to Alexandria under threat of the Italian Fleet, and six merchant ships simultaneously approaching from Gibraltar fell to Axis air attack from Sicily and Sardinia. The non-arrival of the Alexandria convoy was a bitter disappointment since Malta had kept up continuous observation of units of the Italian Fleet at Naples, Palermo, and Taranto. Flying-Officer H.G. Coldbeck, flying the specially-stripped photographic Spitfires of No. 69 Squadron, whose flight he later commanded, made frequent sorties over the Taranto main fleet base, while Squadron-Leader A. H. Harding, of No. 221 Squadron, patrolled in a radar-equipped Wellington outside Naples and Palermo by night. A force of two battleships, four cruisers, and destroyer escort was detected putting to sea from Taranto on 14 June. Beaufort and Wellington torpedo attacks from Malta, supplemented from the Middle East by Liberator bombers of the USAAF, turned the Italian Fleet back, but the Alexandria convoy had by then used so much of its anti-aircraft ammunition in defending itself south of Crete, that in spite of the fact that the way was clear it was ordered to return to Alexandria.[9]

Difficulties only increased once when the Allies were forced to evacuate first Greece then Crete by June 1941. As the land campaign swung in favour of the Afrika Corps the tempo of attacks was increased. The threat was such that at times the convoy system was at the brink of being withdrawn. Ten major convoys were despatched to Malta between January 1941 and December 1941. On 14 November 1941 the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal was torpedoed escorting a Malta convoy. The convoys were now departing from Gibraltar or Alexandria. They were heavily protected by RN warships but losses were very high. There was also a threat from the U-boats but there were never enough of them to affect the strategic outcome.[10] By the end of 1941 four convoys had reached Malta. At this time the Axis submarine and air campaign was stepped up in order to eliminate Malta which was proving a thorn in the Axis supply route to North Africa. Axis convoys were routinely intercepted by aircraft and submarines operating out of Malta. These losses impacted greatly on the ability of the Afrika Corps to conduct the land campaign.

The opening months of 1942 brought a definite strategic plan to eliminate Malta by the Axis powers[11] and the noose was tightened around Malta. This made the life of a seaman in the Malta convoys a nightmare. Even when the merchant ships reached Valletta, they still were subjected to air attack while refuelling.[12] From January to June 1942 three convoys were sent to Malta. Only five merchant ships reached the port. Three of these were soon sunk at anchor in the harbour. Between February and August 1942, nineteen merchant ships were lost while being escorted to Malta.[13] RN submarines did manage to keep supplies coming in but by April 1942 the defenders and civilians were facing extreme food shortages and starvation was imminent. By July, the German plan to invade Malta was abandoned due to the drain on resources caused by the Eastern Front and as a result the air campaign eased. Prime Minister Peter Fraser sent a telegram on the current situation:

The defence of Malta has been an inspiration to us, and we must all hope that it will be possible to retain this strongpoint without too grievous a cost to us in running supplies. The increasing success of enemy attacks on our convoys to Russia is of course a great disappointment to us, as it must be to you and to our Russian friends. The continued gravity of the Axis air and sea attacks on our shipping raises most weighty problems, especially in view of the lengthy and burdensome supply and reinforcement routes that we must maintain, and of the possibility that the Japanese may decide, as there are indications they will, to devote part of their submarine and surface strength to attacks on shipping, both in the Indian Ocean and in the Pacific. The reason for our present increased shipping losses has never been fully understood by us. There was a period when the Battle of the Atlantic seemed to be going well on the whole. We can understand that the comparative unreadiness of the United States to meet the submarine menace in American waters must take priority.[14]

One of the most brilliant actions of the war was fought in the Mediterranean in March 1942 during the passage of convoy MW 10, the commissioned supply ship HMS Breconshire and three merchant ships, from Alexandria to Malta, escorted by four small cruisers and seventeen destroyers. New Zealand officers and ratings were serving in several of the escorts. On 22 March attacks by some 150 aircraft were successfully fought off. The Italians then made two attempts to cut off the convoy, first by one 8-inch and three 6-inch cruisers, and later by one battleship, two 8-inch and four 6-inch cruisers, and a few destroyers. Both attacks were frustrated by the bold and vigorous tactics of Rear-Admiral Vian. The convoy was screened by smoke and the enemy attacked with torpedoes and gunfire. The battleship was torpedoed and hit by gunfire and set on fire and two cruisers were damaged. Sub-Lieutenant Hardingham2 of the destroyer HMS Southwold (she was sunk by aircraft while screening Breconshire off Malta next day) was awarded a mention in despatches for having encouraged his gun crews throughout the action ‘by word and his own personal example.’ Leading Seaman Mackenzie3 of the destroyer HMS Beaufort was also mentioned in despatches, his commanding officer reporting that ‘this rating is captain of X-gun which on all occasions has been first on the target. This is entirely due to his personal leadership and example ….’[15]

The most famous convoy is the PEDASTAL convoy that departed Gibraltar on 10 August 1942. This would be the last convoy to face strong enemy opposition. Out of the fourteen merchant ships that left Gibraltar, only five arrived at Valletta Harbour in Malta. The cost to the Royal Navy was the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, two cruisers, and one destroyer.[16]

Eagle was one of two aircraft carriers lost by the RN in the Mediterranean during the Second World War supporting operations to supply Malta. The arrival of the convoy allowed the air forces on Malta to strike against the Axis forces that were now on the back foot.[17] As the tide turned from October 1942 the interdiction on the convoys lessened. On 16 November 1942 convoy STONEHENGE left Alexandria and despite German air attacks only light damage was suffered by ships in the convoy. In December 1942 the PORTCULLIS convoy arrived in Valletta Harbour in Malta unopposed. This confirmed that the siege of Malta had been lifted as the bogging down of the German offensive in Russia forced an abandonment of the air campaign. In December 1942 Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a telegram to Prime Minister Peter Fraser:

It looks as if Rommel will not stand at Agheila, and by the time this reaches you he may well be taking another big bound backwards. We shall follow hotfoot on his heels. The haunting anxiety that the fortress of Malta would be starved out, which we have endured for so many months and for the sake of which we have made such heavy sacrifices both in warships and supply vessels, has been swept away by the arrival there of a second British convoy from Alexandria [The STONEHENGE convoy].[18]

The failure of the Axis forces to eliminate Malta proved to be a decisive factor in the defeat of Axis forces in the North African campaign as the Official History of the North African campaign notes:

The state of inadequacy of the whole North African supply organisation made any real improvement impossible without a concerted effort and a calculated risk similar to that made by the Allies in relieving Malta. But while the crises in Malta were obvious, that in North Africa was hidden in a smoke screen of promises and wishful thinking. The Italians, and many Germans, made the excuse that their lack of shipping, aggravated by Allied sea and air operations, limited the amount that could be sent to the Panzer Army. Yet there were available in Europe sufficient supplies of all kinds, as well as ships, escorts and air cover, to make possible several ‘Malta convoys’ in which, in spite of possible losses, enough material would have reached Africa to settle the Panzer Army’s problems for some months at least, As it was, the method of attempting a constant trickle of supply not only gave the Allies the opportunity to impede its constancy but made efficient planning impossible. As with the food cargoes mentioned earlier, ships that reached North Africa safely remained in port for long periods, all the time in danger of air attack, through lack of facilities to transport their cargoes to the forward area. The coastal scow service, intended to relieve road transport of long bulk haulage, operated with disconcerting irregularity owing to lack of provision of sufficient vessels and sufficient crews.[19]

This ultimately led to the surrender of Italy in September 1943. In that month the surrendered Italian fleet was interned at Malta.

New Zealanders and the Malta Convoys

New Zealanders played a role in the Malta convoys and the defence of the island. Able Seaman A. Worth served in the battleship HMS Barham escorting the PEDASTAL convoy. In January 1942 when the destroyer HMS Gurkha, one of the escorts of a convoy from Alexandria to Malta, was torpedoed by a U-boat off Sidi Barrani Able Seaman William Armstrong, RNZNVR, regardless of fiercely burning oil on the water, jumped overboard and secured a line round an injured officer, who was then hauled to safety. For this act of gallantry, Armstrong was awarded the British Empire Medal.[20] Two brothers from Timaru, Lieutenant A. G. Tait, RN, and Lieutenant J. F. Tait, RNZNVR, also saw much service in submarines. The latter had previously served in the cruiser HMS Arethusa and the destroyer HMS Ithuriel escorting convoys to Malta.

During the passage of the August 1942 convoy Ithuriel rammed and sank an Italian submarine.[21] Others in the aircraft carriers Eagle and HMS Argus covered the flying of reinforcements of Spitfires and the passage of a supply convoy to Malta in June, when four out of six ships were sunk. A number of New Zealanders were serving in squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm which, under continuous enemy attack, shared with the RAF in the defence of Malta, as well as making frequent strikes at enemy shipping and airfields. Fleet Air Arm pilot Sub-Lieutenant (A) Cramp of 830 Squadron, was awarded the DSC for ‘gallantry in circumstances of extreme hazard.’ At a critical stage in the passage of the June 1942 convoy, he led from Malta a flight of four Albacores[22] in a strike on an Italian force of two cruisers and five destroyers and hit one of the cruisers. Sub-Lieutenant (A) Morrison of 828 Squadron gained a DSC for ‘great bravery, skill and determination’ in torpedo and dive-bombing attacks on enemy shipping. He had taken part in more than twenty operations from Malta up to June 1942.[23]

The Malta convoy of August 1942, in which nine out of fourteen merchant ships and four escort vessels were lost, was covered as far as the narrows of Skerki Channel by the aircraft of three carriers. HMS Eagle was sunk soon after HMS Furious had flown off thirty-six Spitfires for Malta, but the New Zealanders in her were among the 900-odd officers and men saved. HMS Indomitable was hit three times and her fighters had to fly-on to HMS Victorious, whose aircraft fought more than twice their own number. The sixty fighters available after the loss of the Eagle destroyed thirty-nine enemy aircraft at a cost of thirteen. Fleet Air Arm pilots Lieutenant (A) Pennington and Sub-Lieutenant (A) Richardson, both of 809 Squadron in the Victorious, were awarded the DSC and Sub-Lieutenant (A) Long, of 885 Squadron, was mentioned in despatches. Pennington showed ‘great dash and initiative in combats with superior numbers of enemy fighters and bombers. Though his aircraft was hit early in the action and the air gunner wounded, he carried out further patrols and helped to account for four enemy aircraft.’ Richardson’s presence of mind, coolness, and accurate direction as observer enabled his pilot to escape from many tight corners. This was Long’s first combat operation and, though his aircraft was damaged, he partly disabled two enemy bombers.

Lieutenant A. B. Napper, air engineer in Victorious, who had previously been mentioned in despatches, was awarded the DSC for his ‘tireless devotion to duty in repairing damaged and unserviceable aircraft, besides assisting in the operation of aircraft on deck.’ Chief Petty Officer Walker, RNZN, who was serving in Indomitable, was awarded the DSM for bravery and dauntless resolution’ when the ship was bombed and aircraft caught fire in the hangar. He had previously served in the cruiser HMS Naiad during the operations in Norwegian waters in 1940 and the battle for Crete in May 1941, as well as with 806 Squadron, Naval Air Arm, in the Western Desert. [24] Lieutenant McNaught was radar officer in the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Cairo which sailed with two convoys to Malta in 1942. She was twice in action with two Italian cruisers and four destroyers during the passage of the June convoy in which four out of six ships were sunk. Cairo was sunk in August when nine out of fourteen ships of the convoy were lost.[25]

Bibliography:

Bruce, Anthony, Cogar, William, An Encyclopedia of Naval History, New York: Facts on File, 1998.

Documents Relating to New Zealand’s Participation in the Second World War 1939―45 Volume II: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951.

Humble, Richard (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983.

Thompson, Wing Commander H. L., New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force Volume III, The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1959.

Walker, Ronald, Alam Halfa and Alamein: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1967.

Waters, S.D., The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956.

Whelan, J. A., Malta Airmen Episodes & Studies Volume 2: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1950.

[1] Richard Humble (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983, p. 261.

[2] Anthony Bruce, William Cogar, An Encyclopedia of Naval History, New York: Facts on File, 1998, p. 237.

[3] Richard Humble (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983, p. 260.

[4] ibid., pp. 260-261.

[5] ibid., p. 261.

[6] J.A. Whelan, Malta Airmen Episodes & Studies Volume 2: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, 1950, p. 21.

[7] ibid., p. 22.

[8] ibid., p. 23.

[9] ibid., p. 24.

[10] Richard Humble (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983, p. 262.

[11]J.A. Whelan, Malta Airmen Episodes & Studies Volume 2: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, 1950, p. 21.

[12] Richard Humble (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983, p. 262.

[13] ibid.

[14] Documents Relating to New Zealand’s Participation in the Second World War 1939―45 Volume II: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, 1951, p. 118. Telegram dated 14 July 1942.

[15] S.D. Waters, The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956, p. 486.

[16] Anthony Bruce, William Cogar, An Encyclopedia of Naval History, New York: Facts on File, 1998, p. 237.

[17] Richard Humble (ed.), Naval Warfare: An Illustrated History, London: Orbis Publishing, 1983, p. 263.

[18] Documents Relating to New Zealand’s Participation in the Second World War 1939―45 Volume II: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, 1951, p. 150. Telegram dated 6 December 1942.

[19]Ronald Walker, Alam Halfa and Alamein: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, 1967, p. 206.

[20]S.D. Waters, The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956, p. 486.

[21]ibid., p. 506.

[22] A torpedo bomber that was introduced to replace the Swordfish.

[23]S.D. Waters, The Royal New Zealand Navy: Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1956, pp. 508-509.

[24] ibid., pp. 510-511.

[25] ibid., p. 520.