Learn about the events that took place in the Battle of the River Plate, including ships details, British and German Strategy, the aftermath and New Zealanders killed.

View a gallery of images from the Battle, aftermath and homecoming.

View a video of the scuttling of the Admiral Graf Spee.

KMS Admiral Graf Spee

Named after the First World War admiral, Maximilian Graf von Spee, KMS Admiral Graf Spee was one of a class of three armoured ships (panzerschiff) designed to protect Germany’s Baltic trade. Following the end of the war Germany had been partitioned, with the two segments separated by Poland and there was a need to be able to protect convoys from potential attack by a French squadron of cruisers or a modernised battleship. To this end the ‘Deutschland’ class were given an armament powerful enough to defeat the envisaged enemy and a speed great enough to out-run ships with superior armament. The result was a class of ships mounting 28cm (11 inch) guns, diesel powered with a speed of 26-27 knots.[1]

Admiral Graf Spee herself was launched by Herbuta von Spee, daughter of the ship’s namesake, on 30 June 1934 and commissioned into the Kriegsmarine on 6 January 1936. Proudly displayed on the large control tower of the ship was a scroll with the word “Coronel”, the place of Admiral Spee’s victory over a British cruiser squadron in 1914. The ship benefited from the experience of her two predecessors, having better armour protection and improved engines. While these resulted in a greater displacement of 16,200 tons (officially 10,000 tons), the ship achieved 28.5 knots on trials, making her the fastest of the trio.[2]

For all their positive features the panzerschiffs had some serious shortcomings. Foremost of these was that their sea-keeping qualities were poor, a factor of the amount of equipment crammed into them, simply overloading the hull. In any sort of sea way the ship rolled and pitched, taking water over the bow and with spray obscuring the view from the lower control positions. One of the captured British Captains on Graf Spee later recalled that rounding Cape of Good Hope the ship rolled and pitched, the sea broke across her and time after time the bows were buried with green water over the forward gun turret.[3]

German Naval Strategy

In 1928 when the first panzerschiff was approved, the role of the German Navy was unclear. On one side were those who saw it as an adjunct to the Army, with little or no function on the high seas, while on the other were those who envisaged a powerful navy which could fulfil the vision of the High Seas Fleet of being able to take command those seas. By 1934 when Hitler came to power, the matter had been resolved in favour of traditional sea power, for which a strong battle fleet was to be created. By 1948 this fleet would have comprised 8 battleships, 2 battle cruisers, 3 panzerschiff, 16 cruisers, 2 aircraft carriers and about 270 U boats.[4] To facilitate this building programme, a naval treaty was negotiated with Britain in 1935 and later with the acknowledgement that war with Britain was possible, Hitler ordered a speeding-up of the construction programme at the end of May 1938.[5]

Following the directive that Britain should be considered a potential enemy, there was a review of German naval strategy. This concluded that, even given the assumption that sufficient time would be made available to complete the planned build-up, cruiser warfare (guerre de course) against British merchant shipping was the only viable option. This would be undertaken by both major surface units, including the battleships, and U boats.[6]

British Naval Policy

British naval policy for the protection of merchant shipping in the event of a war with Germany and/or Italy was laid down in a memorandum of January 1939. This document stated that traditional and well-proved methods of protecting British trade would be implemented. A system of adequately escorted convoys would be introduced and where this was not possible evasive routing and dispersal of shipping would be implemented. Cruisers would be concentrated in pairs at focal points where they could be supplemented by units of the main fleet if required. The armament and speed of the three Deutschland’s made them a particularly difficult problem for the Royal Navy.[7]

HMS Achilles

Half a world away, HMS Achilles, one of New Zealand’s two cruisers, had sailed from Auckland on 29 August heading for Balboa at the western end of the Panama Canal, where it was to join the Royal Navy’s America and West Indies Squadron in the Caribbean. On 2 September these orders were changed and Achilles was instead to patrol the west coast of South America. The signal to commence hostilities was received on board on soon after midnight on 3 September but no ships were sighted until arrival at Valparaiso on the 12th. Having fuelled and embarked fresh provisions Achilles, in strict observance of the neutrality laws, sailed the next day for what would be a six week patrol off the coasts of Chile, Peru and Ecuador. [11]

Immediately prior to the outbreak of war the South Atlantic had been designated a separate station, with the Commander in Chief based at Freetown, Sierra Leone and the South America Division of the America and West Indies Squadron was transferred to the new station. At that time the Division consisted of the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter and a sister ship to Achilles, HMS Ajax, but only Ajax was actually in South American waters. Exeter, wearing the broad pennant of Commodore Henry Harwood, had been at Plymouth with the crew enjoying Foreign Service leave. This had been curtailed on 23 August and the ship sailed later that day for South America.[12]

Exeter arrived on the newly established station on 1 September and over the next few weeks the Division was augmented by another 8 inch gun cruiser, Cumberland and two destroyers.[13] On 2 October Achilles was also ordered to join the Division and the ship headed south before making its way through the straights of Magellan to the South Atlantic. However, it was not until the 23rd that the ship sailed from the Falkland Islands ready for its new duties.[14]

The considerably increased strength of the South America Division was partly due to the importance of the trade from that part of the world and partly because of a significant change in Admiralty policy for trade protection. This new policy was promulgated on 5 October and established eight hunting groups, which were to seek out and destroy enemy raiders. Most of these groups comprised two 8 inch gun cruisers, which were deemed capable of destroying a panzerschiff or ‘Hipper’ class cruiser. The hunting group off the South American coast was designated “Force G” and made up of Cumberland and Exeter.[15] With these two cruisers absent hunting raiders there was a need to supplement Ajax on routine patrol and escort duties, hence Achilles redeployment from the West Coast. As the hunting groups were to observe strict radio silence Commodore Harwood transferred his broad pennant to Ajax.

Shortly after receiving the message to begin operations against British shipping, Admiral Raeder sent another, reiterating his order that Graf Spee was not to enter into any action against British warships. This was intended to prevent any possibility that Britain would gain prestige from a successful action on the part of the Royal Navy.[16] Graf Spee’s first success was against the SS Clement off the coast of Brazil on 30 September. Captain Langsdorff took the Captain and the Chief Engineer aboard and as Clement had got off a message about being attacked by a raider, he sent a message in plain language to the nearest radio station, asking that the boats of Clement be picked up. This message was signed “Admiral Sheer” to confuse the British about the identity of the raider.[17]

Four more ships fell victim to Graf Spee over the next three weeks, mainly in the mid South Atlantic. Then to confuse the issue, Captain Langsdorff moved into the Indian Ocean, sinking the steamer Africa Star there on 15 November and stopping a neutral Dutch ship the following day. Satisfied that the British would be aware that the raider was now operating in the Indian Ocean, Graf Spee began the return journey to the South Atlantic.[18]

On 24 November Captain Langsdorff told his officers that it was time for the ship to return to Germany and that he had decided to revise the tactics employed to date. Because the ship was returning to be refitted and it was unlikely that another German ship would be in the area for some time, Graf Spee would not avoid action with enemy ships, but would meet them, even at the risk of losing the ship.[19]

Back in the South Atlantic Graf Spee sank the Doric Star on 2 December and the Tairoa on the 3rd. On board Ajax Commodore Harwood reflected on the situation. From the area of these sinkings off the African Coast, he estimated that at a cruising speed of 15 knots the raider could be off Rio de Janeiro on the morning of 12 December, the River Plate on the morning of the 13th or the Falkland Islands on the 14th.[20] In a report to the Admiralty in late October the Commodore had expressed his view that in order of importance, the key areas on the east coast of South America were the focal areas of the River Plate and Rio de Janeiro.[21] Accordingly he decided to concentrate his force there. He had available three ships, Ajax, Exeter and Achilles, as Cumberland was undertaking routine self maintenance at the Falkland Islands.[22]

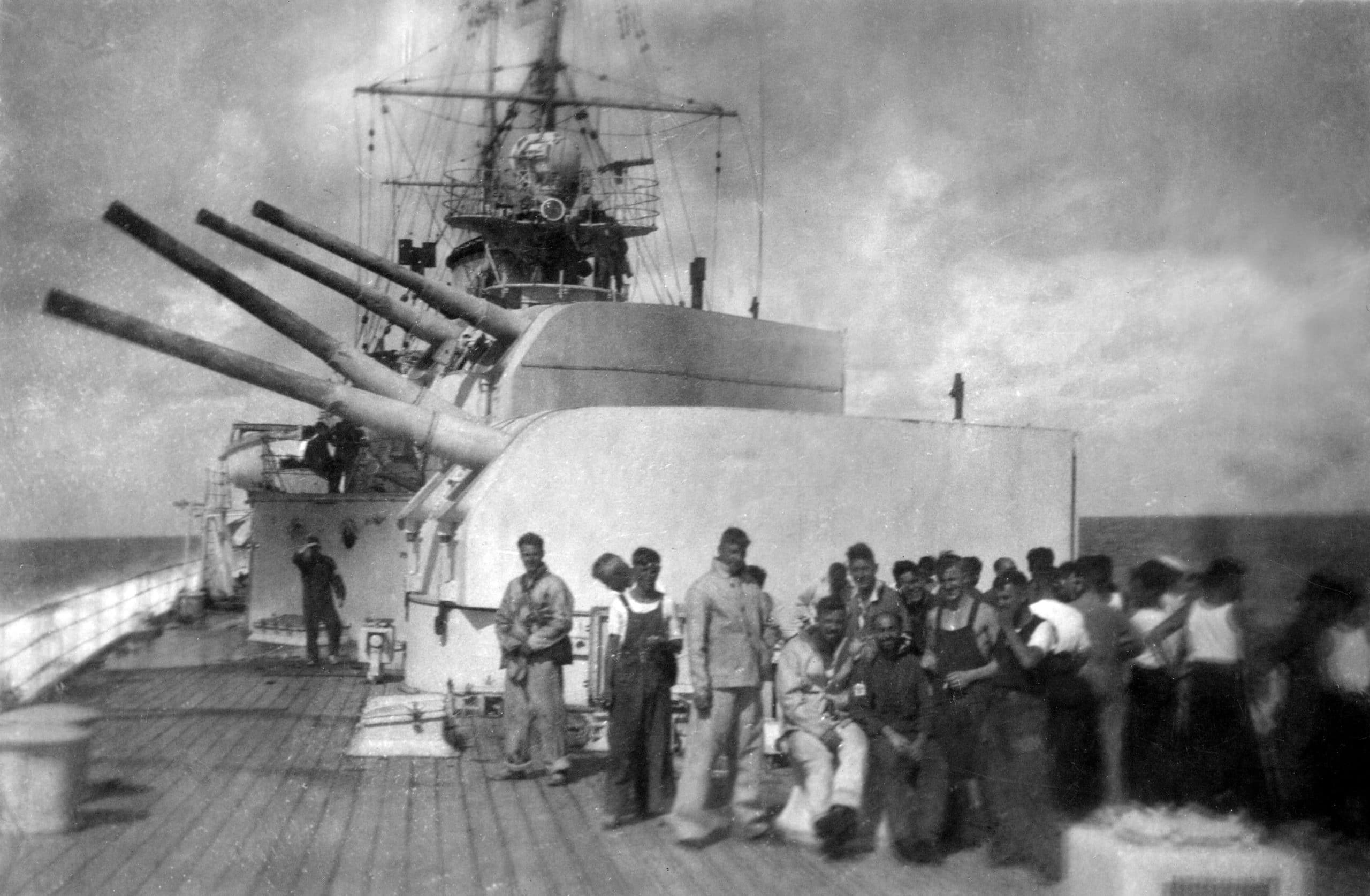

HMS Exeter before the battle

Commodore Henry “Bobby” Harwood had been the Commodore, South America Division since 1936. The fifty year old had joined the Royal Navy in 1903 and become a torpedo specialist, serving in that capacity during the First World War, first in a destroyer and later in the battleship Royal Sovereign. Between 1934 and 1936 he was on the staff of the Senior Officer’s War Course at Greenwich. There he lectured in tactics, a subject which was undergoing a transformation in the Royal Navy at that time. One of his innovative developments was how best to engage the new German pocket battleships, using separated divisions of cruisers that would force the enemy to split his fire or only engage one division at a time.[23]

At 6.00am on 12 December the three ships made a rendezvous off the River Plate and exercised together for the first time. At midday the Commodore signalled his intentions:

My policy with three cruisers in company versus one pocket battleship – attack at once by day or night. By day act as two divisions, First Division and Exeter diverged to permit flank marking. First Division will concentrate gunfire. By night ships will normally remain in company open order.[24]

On the morning of the 13th the ships went to dawn action stations as usual and practiced the Commodore’s intended method of attacking a pocket battleship, after which the crews stood down into cruising watches, most going below for their morning shave and breakfast.[25]

War

At midday on Sunday 3 September 1939 Admiral Graf Spee, under the command of Captain Hans Langsdorff, was in mid Atlantic Ocean about 650 miles north west of the Cape Verde Islands, cruising in calm seas. Following in her wake was the supply ship Altmark.

Some 2,000 miles to the north Graf Spee’s sister ship, Deutschland was cruising south of Greenland. Both ships had sailed from Wilhelmshaven the previous month, Graf Spee on the 21st and Deutschland on the 24th.

At the beginning of September the Royal Navy had placed a patrol from Greenland to Scotland, but this was far too late to detect the German ships.[8]

In the immediate aftermath of the First World War Captain Erich Raeder wrote the German Navy official history of surface raiders, drawing the prime conclusion that the raiders would have been more effective if their commanders had avoided action with British warship.

As Supreme Commander of the German Navy in 1939 Admiral Raeder, was determined that his raiders would not make the same mistake. The German Battle Instructions made it clear that combat, even against inferior naval forces was to be avoided, and an instruction of which Graf Spee was reminded at the end of September. [9]

Graf Spee’s primary operational area was the South Atlantic, but it was also authorised to operate in the central Atlantic and southern Indian Ocean.

However, for over three weeks Hitler still tried to make peace with Britain, forbidding operations that would hinder his efforts in that direction and it was not until 26 September that Captain Langsdorff received orders to operate against British shipping.[10]

The Battle

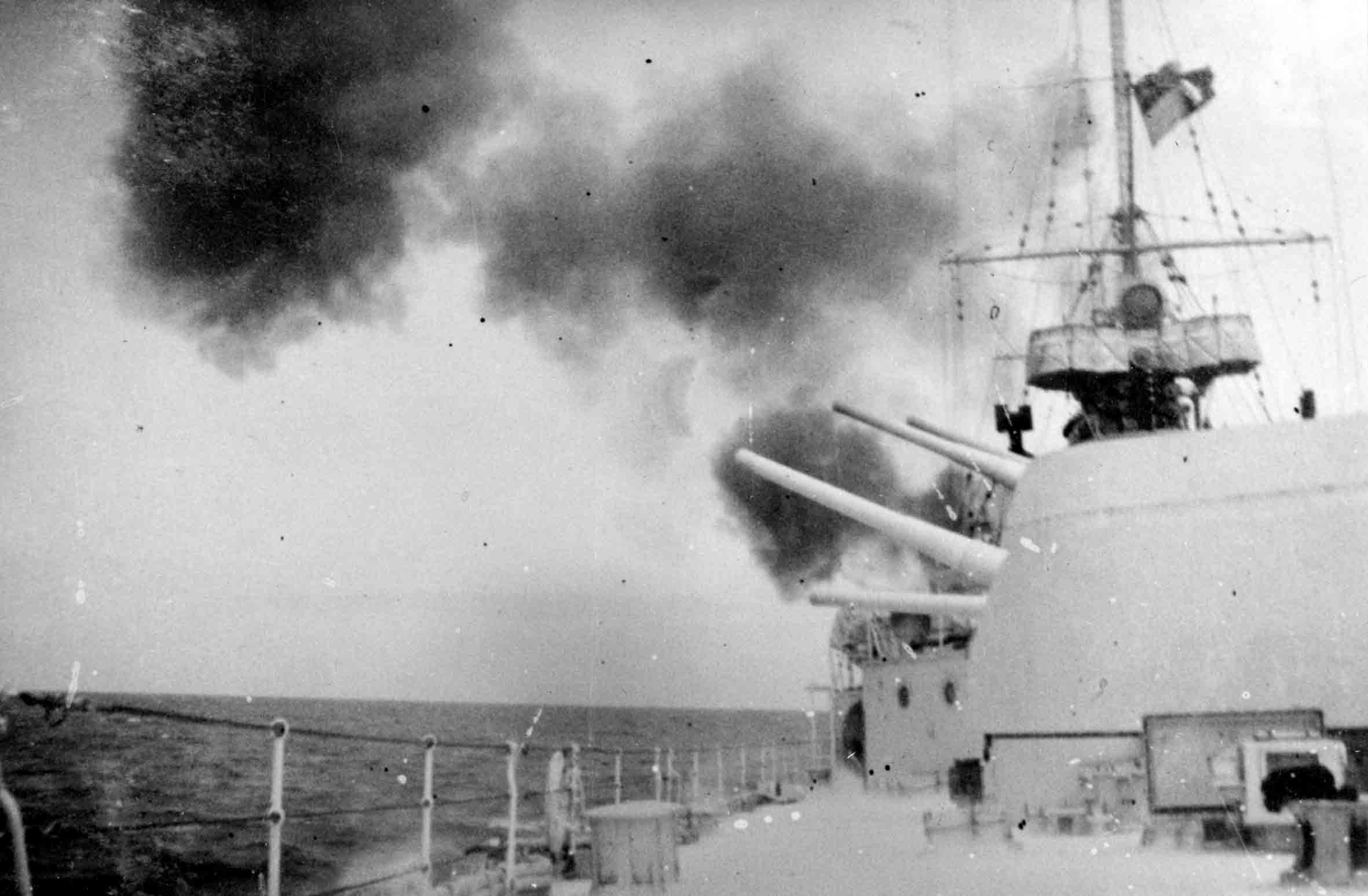

It was shortly after 6.00am and the ships were steaming in line ahead, Ajax leading, followed by Achilles and Exeter, when the signalman on watch in Ajax reported smoke on the port horizon. At 6.14am Exeter was ordered to investigate and turned on to the bearing. Two minutes later she reported that the contact was a pocket battleship. Graf Spee was steering directly towards the three ships and opened fire at this time. All ships ran up their battle ensigns, the largest ensign carried, Achilles also hoisted the New Zealand flag. Graf Spee’s target was the main threat to her, Exeter and after dropping 400 yards short with her first salvo, straddled the ship with the second and the third landed close alongside, causing damage to the ship’s gunnery and steering communications as well as killing a number of men. About this time Exeter opened fire and straddled Graf Spee with the third salvo. Shortly afterwards a hit was landed on Graf Spee which disabled a 4.1 inch anti aircraft mounting, but most importantly, also knocked out the ship’s fresh water plant.[26]

Seven minutes after opening fire Graf Spee scored a hit on ‘B’ turret, immediately forward of the bridge, of Exeter. This disabled the turret and swept the bridge with splinters, killing or wounding most of the men there and severing communications with the wheelhouse. Wounded in both legs and both eyes, the Captain was forced to move to the after control position. Even there direct communication with the after steering position was not possible and orders had to be passed by a chain of sailors. Continuous hits and near misses hammered the ship and caused more casualties over the next five minutes. Then Exeter got a short respite.[27]

In accordance with the Commodore’s plan, while Exeter exchanged fire with Graf Spee, Ajax and Achilles crossed to the opposite side of Graf Spee. At 6.22am Achilles opened fire, followed by Ajax at a range of just over 19,000 yards (9.5 nautical miles), the fire being returned by Graf Spee’s secondary armament. By 6.31am the range was down to 13,000 yards – the optimum for the 6 inch cruisers – and they were rightly seen to be a threat by Graf Spee, which shifted target to Ajax. That ship was straddled several times and Commodore Harwood altered course slightly away to throw off the fire. Captain Langsdorff was also worried about the actual position of the ships from a tactical perspective and also altered course. The result was that the range between Graf Spee and the light cruisers opened and Graf Spee again concentrated on Exeter. By now the British ship had only four of her six guns working, but despite the hammering she was receiving she managed to hit Graf Spee twice. The second of these later caused great concern to Captain Langsdorff, when it was found that it penetrated the main armour belt. While the shell caused considerable damage anyway, if it had landed a metre further aft, it would have exploded in the engine room.[28]

After five minutes of this punishment Exeter was showing signs of distress, with all guns out of action. Graf Spee again shifted target to the light cruisers and at 6.40am landed a near miss by Achilles. This killed several men, some of the 4 inch gun’s crew on the upper deck and others in the Director Control Tower, besides wounding several, including Captain Parry and Chief Yeoman of Signals Martinson, on the bridge. While the Director was not seriously damaged, it took some time to replace the dead and wounded and although the ship continued firing, it was ineffective for about ten broadsides. Achilles inaccurate shooting was compounded by confusion on the part of Ajax’s aircraft which reported that it was Ajax was missing the target not Achilles, an error which was not detected by the Gunnery Officer of Ajax until about 7.06am.[29]

At about 7.00am Graf Spee shifted fire again to Exeter, which was still engaging her with the after turret, in local control and despite the fact that one of the two guns had difficulty in loading. However, Graf Spee was also experiencing problems with her forward turret at this time and did not make any further hits. Exeter’s fire was also inaccurate and at 7.15am Graf Spee again shifted target to the light cruisers, which were closing the range. By 7.25 the range was down to 8,700 yards and the two ships were hitting Graf Spee, when Ajax received a hit on ‘X’ turret, which also put ‘Y’ turret out of action. At this close range, Achilles, with her fire control system fully functional again, was making hits on the German ship.[30]

The power failed to Exeter’s last turret at 7.30am and by 7.40am the ship was unable to keep up the high speed of the action and turned away. But Graf Spee was beginning to suffer. One shell hit the top of the control tower and Langsdorff was wounded in his shoulder and arm by splinters from the blast. A second hit below the control tower shortly afterwards, knocked him out for a few minutes. Among the other hits was one that entered the starboard bow and caused major structural damage when it exploded on the other side of the ship, blowing a hole in the port side. Another hit was registered by a practice round fired by ‘B’ turret of Achilles, which entered on the starboard quarter and after doing some superficial damage, but killing two men, came to rest in the warrant officers quarters.[31]

While it was apparent that the two ships were hitting Graf Spee, to remain at 8,000 yards of what was still a powerful and active opponent – the ships were being engaged by both Graf Spee’s 11 inch guns and her 5.9 inch secondary armament – was risky. To emphasise the danger Ajax’s main topmast was shot away at 7.38am and several casualties were inflicted on personnel stationed on the after superstructure.[32]

About this time the Commodore received a report that Ajax was down to 20 percent ammunition remaining. Weighing all the factors: Exeter was out of action; Ajax had two turrets knocked out and was short of ammunition; Graf Spee was apparently still able to steam at full speed and all her armament was still firing with considerable accuracy, Commodore Harwood decided to break off the action and take up a shadowing position.[33]

The two ships turned to the east under cover of a smoke screen and opened the range. Graf Spee continued westward while Captain Langsdorff considered his position. The ship had received numerous hits and while none of them threatened the ship directly, the hit in the bow would impinge on the already marginal seaworthiness of the ship and the loss of the freshwater plant was a major impediment for a long sea journey. Graf Spee had received 23 hits, 37 men had been killed and another 57 wounded, including of course, Langsdorff himself. Additionally the ship had fired over 414 rounds of 11 inch ammunition, 70 percent of its outfit. Having toured the ship Captain Langsdorff decided to enter the neutral port of Montevideo to make good as much of the damage as possible and review the options available to him.[34] The destruction of the steam plant stopped supply of steam to the galley. It also had a secondary and more critical part in the ship’s operation. Steam from the plant was supplied to the turbine generated diesel centrifugal separators. This piece of equipment is carried because diesel is carried aboard the warship as crude oil that has high water content. To make it combustible it has to pass through a centrifugal separator to eliminate the water and the useable fuel is pumped into holding tanks and replaced as it is consumed. Langsdorff only had the fuel in his holding tanks leaving him no option to make for the nearest port to repair the steam plant. This vulnerability was kept as a closely guarded secret as other warships such as KMS Admiral Scheer & Lutzow had the same arrangements and were open to suffering a similar fate. Other German warships had steam turbines, also had diesel cruising engines. German officers who were interned in Argentine were smuggled across the border into Chile and then back to Germany to pass on this vital information to the Kriegsmarine.

While this was taking place on board Graf Spee, Commodore Harwood was making his arrangements. Exeter was ordered to the Falkland Islands to make those repairs which were possible, Cumberland was ordered to curtail its maintenance and rejoin the Division and the world was told about the presence of the raider off the mouth of the River Plate. It was also a relief to be informed that while the ships had expended a large amount of ammunition during the 80 minutes of the battle, the report of Ajax having only 20 percent remaining, referred only to ‘A’ turret, which had fired the most rounds.

Shortly after 10.00am Achilles had unwittingly closed the range to 23,000 yards and Graf Spee responded with two 11 inch rounds, one of which fell alongside Achilles. With nothing to be gained by risking unnecessary damage, the range was rapidly opened. Twice during the afternoon Graf Spee fired at Achilles, but without causing any damage. Again at 7.15pm Graf Spee fired two rounds at Ajax the first short, but the second landed in the ships wake astern as it reversed course to open the range.[35]

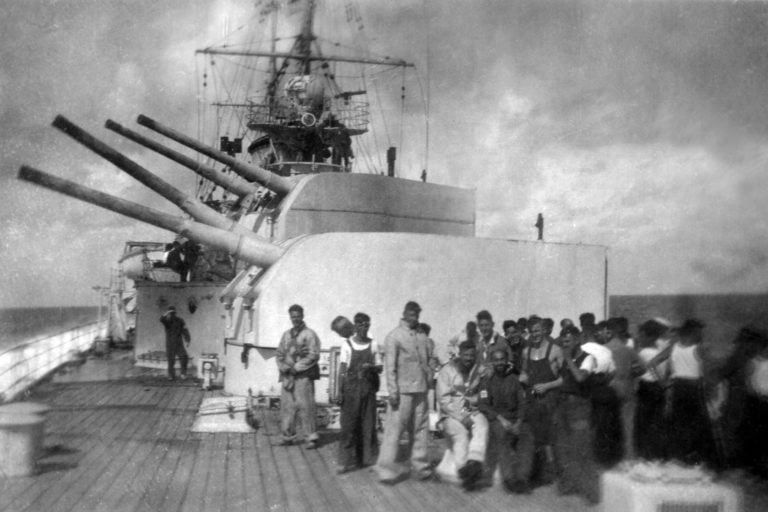

Damage showing to Achilles DCT

Admiral Raeder’s approval for the ship to enter Montevideo was received in Graf Spee during the afternoon and shortly after midnight the ship anchored in the harbour. A new type of battle over the fate of the German ship now began.

Captain Langsdorff asked to stay in the port for two weeks to repair the battle damage and at first the British Ambassador, Sir Eugene Millington-Drake argued that the ship was essentially seaworthy, having steamed over 300 miles the previous day, and that the stay should be limited to 24 hours. The Uruguayan authorities decided to permit the ship to stay for 48 hours. The nearest reinforcements for Commodore Harwood were over five days away and he asked the Ambassador to do what he could to delay Graf Spee sailing. This he initially did by arranging for a British merchant ship in the harbour to sail, as a clause in the Hague Convention would preclude Graf Spee sailing for 24 hours.[36] While the Uruguayan’s agreed to this, it was reiterated that Graf Spee had to leave the port by 8.00pm on 17 December. In addition to his diplomatic efforts, Millington-Drake was also disseminating disinformation. One classic instance of this was requesting the Argentine authorities, in plain language over a telephone line known to be tapped by the Germans, to arrange fuel for two battle cruisers expected to arrive the following day. Some of this bore fruit in that the Gunnery Officer of Graf Spee reported that he had sighted the battlecruiser HMS Renown, from the foretop and later reported sighting the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and three destroyers.[37]

The ‘sighting’ of the British capital ships, combined with the disinformation and the knowledge that his ship could not be repaired sufficiently in three days for either battle or a long voyage, presented Captain Langsdorff with three alternatives. He could try to break out through the British line, he could let Graf Spee be interned or he could scuttle the ship. Berlin was advised of these options and responded with the order that he was not to allow the ship to be interned. What was perhaps a key factor in the Captain’s decision making process was revealed in a comment made to one of his crew later, “better a thousand live young men than a thousand dead heroes”. Langsdorff decided to scuttle the ship.[38]

This final decision was made early in the morning of 17 December and at 4.50am destruction of key equipment was begun. This included the fire control system, but inexplicably, not the ship’s radar set. Preparations were made for the scuttling and during the day boats were called from Buenos Aires in nearby Argentina, which had a large German population and most of the officers and ratings were eventually taken there. Shortly after 6.00pm, with battle ensigns on both the fore and main masts, Graf Spee weighed anchor and proceeded out of harbour. There were 41 men on board with Captain Langsdorff. About an hour after sailing and four miles off the coast, the ship stopped. The two battle ensigns were hauled down and the ship was evacuated. At 7.54pm the first of the scuttling charges went off and Graf Spee began to settle on to the mud of the estuary.[39]

The Aftermath

Graf Spee’s officers and ship’s company were formally interned in Argentina on 19 December, despite efforts to have them recognized as shipwrecked sailors and thus not liable to internment. That afternoon Captain Langsdorff mustered his crew and spoke to them, being positive about their welcome and assuring them that they would be looked after by the local German community. That night he wrote three letters, one to the German Minister, one to his wife and one to his parents. In the first he explained his actions in scuttling the ship and his feelings as the person bearing sole responsibility for its fate. Included was the statement that “For a captain with a sense of honour, it goes without saying, that his personal fate cannot be separated from that of his ship”.[40] This done, he unfolded the ensign worn by Graf Spee during the battle, laid down on it and shot himself in the head.[41]

A grateful sovereign made Commodore Harwood a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath and each of the Captains was made a companion of the same Order, while the Admiralty promoted Harwood to Rear Admiral. The awards were announced during the waiting period off the mouth of the River Plate, as the Commodore noted in a letter to his wife “Showered with honours before the job was done”.[42] In February more awards were made to the ships, each of the Executive Officers received the Distinguished Service Order, as did another officer; six officers each in Exeter and Ajax received the Distinguished Service Cross, as did four in Achilles; and 17 men in Exeter and 14 each in Ajax and Achilles received the Distinguished Service Medal. Additionally three men in Exeter and one in Achilles were awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.[43]

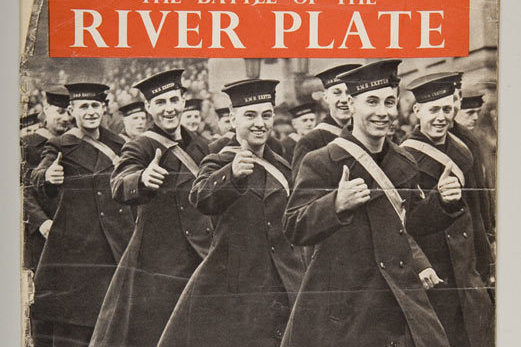

Immediately following the scuttling the crews of Ajax and Achilles resumed their patrol, but perhaps in a reflection of the release of tension overnight, they did not go to the routine action stations at dawn. The ships then proceeded to the Falklands where they sent working parties to help repair the damage on Exeter and spent Christmas. In the New Year Exeter proceeded to Britain for repairs while Ajax visited Montevideo and Achilles Buenos Aires. The ships were well received at both places and when by chance some Achilles sailors met with some from Graf Spee ashore; there was no animosity between them. At the end of January Achilles departed for home, arriving to what amounted to a state welcome in Auckland. The Governor General met the ship with the Deputy Prime Minister and there was a civic luncheon in the Auckland Town Hall, during which Mr Tai Mitchell presented Captain Parry with a Maori cloak on behalf of the Maori people, to be worn should the ship go into battle again.[44]

In early 1940, in collusion with British Naval Intelligence, a Uruguayan citizen purchased the hulk of Graf Spee, with the expressed intention of selling the metal to British and Italian firms. In this way the British were able to inspect the wreck first hand and remove some vital pieces of equipment, such as the radar set, fire control equipment and a torpedo war head which had been set as a scuttling charge, but which had not exploded. In all about 30 tons of equipment was removed and shipped back to Britain.[45]

In human terms the cost of the battle was relatively light. Exeter had 61 killed, Ajax 7 and Achilles 4, in addition to which a total of 47 men were wounded. Graf Spee lost 36. The German dead were buried in Montevideo, the British at sea, although two bodies from Achilles later washed ashore and were buried in Uruguay.

Since 1945 there have been annual commemorations of the battle in New Zealand, Britain and Germany. Occasionally visits by all nationalities to South America have taken place, the most notable in 1979. In New Zealand the city of Auckland renamed a point on the harbour edge ‘Achilles Point’, while some previously unnamed peaks in the South Island were given the names of the ships involved in the battle. On a grander scale, the town of Ajax in Ontario, Canada has named its streets and public places after those involved in the battle.

Achilles Voyage Home to New Zealand after the Battle

After the Graf Spee was scuttled, Achilles spent the night off the port. On Monday 18 December she proceeded to San Borombon Bay in company with Ajax and refuelled from the tanker RFA Olynthus. That evening, Rear-Admiral Harwood came aboard and addressed the ship’s company of Achilles. Later that night in company with Ajax, both ships set course for the Falkland Islands and arrived there on 21 December.

On 22 December, the three seriously wounded men from Achilles were transferred ashore to the King Edward Memorial Hospital which was also treating the wounded from Exeter & Ajax.

A party of men from Achilles was sent to Exeter to assist with repairs. That evening, after refuelling, Ajax & Achilles departed in company and they returned on 24 December. That day the cruisers HMS Dorsetshire & Cumberland arrived. From the 25-29 December the cruisers remained in port riding out a storm that passed through the islands. Despite this, Achilles refuelled and replenished her ammunition. The wounded ratings returned to the ship on the 29th.

On 30 December 1939, Ajax & Achilles in company departed Port Stanley for the River Plate. On the morning of 3 January 1940 Achilles parted company and proceeded up the River Plate into Buenos Aires to be warmly welcomed. It then proceeded to and remained there from 3 to 5 January. Presents and donations for the welfare fund were handed over to the ship. Ajax went to Montevideo to a rousing reception. Achilles left Buenos Aires on 5 January and joined with Ajax and the cruisers HMS Dorsetshire & Shropshire. This Division was under the command of Rear-Admiral Harwood who transferred his flag to Achilles when she joined up with the ships that would remain on patrol. Ajax detached that night and made passage for Britain

After eight days on patrol, Achilles arrived back at Port Stanley on 14 January. It had been proposed that Achilles proceed to Malta for a refit when she was relieved by HMS Hawkins. Harwood convinced the Admiralty to return the cruiser to Auckland for the refit. After replenishment, Achilles left Port Stanley on 16 Janaury and patrolled north to Rio de Janerio. On 26 January, she stopped for 24 hours at Montevideo. She then resumed patrolling and refuelled from the tanker RFA Olwen off the Rouen Bank on 28 January and anchored. The next morning she was joined by Hawkins and Harwood transferred his flag to the newly arrived warship. On the afternoon of that day Achilles returned to Montevideo to collect mail.

On 1 February Achilles arrived at Port Stanley for the last time. After preparations, she departed on 2 February and set course for New Zealand. She transited the Magellan Strait on 4 February and arrived in Auckland harbour on 23 February.[46]

New Zealanders Killed at the Battle of the River Plate

Biographical Sketches

At the Battle of the River Plate, HMS Achilles ship’s company numbered 567 officers and ratings of which five officers and 316 ratings were New Zealanders. At that time this was the largest number of New Zealanders to have served in a warship. During the battle at 0640 a shell fired from Graf Spee towards Achilles fell short in line with the Bridge on the starboard side and exploded on hitting the water. Apart from killing the four men, it wounded the Commanding Officer Captain Parry and the Chief Yeoman.

The relatives of the four men killed were telegrammed from the Minister of Defence on 15 December 1939 followed by letter dated 16/12/1939:[47]

They [the Naval Board] feel, however, that it will be some consolation to you in your loss that your son, …., lost his life while engaged in a most gallant naval action which has stirred the world, and of which the New Zealand Naval Forces in particular have the greatest reason to be intensely proud.

I am, dear Sir, Yours most sincerely

N.T.P. Cooper, Naval Secretary

From Commissioned Gunner Eric J. Watts’s personal account while in the Director Control Tower which was hit by six large splinters from the shell:

During the whole action Spey twisted and turned and altered speed. At one time T.S. suggested 10 knots. I don’t think this was accepted. She turned a remarkably quick and small circle, almost like a speed boat. Concentration was not excellent and Spey turned under smoke. Shortly after this a number of casualties were received in the D.C.T. (Director Control Tower). Ajax had turned and crossed our line of fire and I think it was as the two ships were passing a salvo of Spey’s straddled both. I heard glass shatter and looking round, saw Sherley falling down and yelling – the two telegraphists fall [sic] together, one fell down the manhole to the Range-finders and being hung by his legs, the other falling on top. I saw that his head was shattered. The Gunnery Officer also called out and I saw his head was also bleeding. I got out [the] First Aid bag and ripped off yards of dressing to make a pad for the Telegraphist and I would fell his neck pulse still jumping. The Gunnery Officer asked me for some (this is when I first saw his gore).

At this moment the T.S. reported no signals. I just laid the pad on the Telegraphist, and we, Sherley, Trimble and I, pulled him out flat in the tower. This Tel. coughed and choked as we moved him. The other one dropping down into the Rangefinders. I then realised that Trimble and Sherley were badly hurt. But we were back in single ship and I returned to my inclinating. The Trainer at this moment told the R. to E. operator to “Bear up”, thinking it was he who was moaning. The Layer also called out, “Are you alright, Shaw?” A moan was heard, which was either Trimble of Sherley. Trimble was still at his post of spotting. The Layer and Trainer both called out that “Shaw’s gone, Sir”. The Inclination transmitter operator was told to take over the R. to E.. It appears that several salvoes must have been fired with no correction to R. to E.. I heard some one call out “A.C.P take over” and then the gunnery officer cancelled it. Medical parties were called for but went away when they found they could not get through the damaged door. I looked over at Trimble several times and could see he was in pain, but he made no fuss. Sherley by now was also quiet. As soon as a lull occurred I went over to him. The medicals had been up again and had got in and applied a dressing to Sherley who they thought was the only one. The D.C.T crew were so concentrated on their job that no one had seen CPO Cook Luke arrive and go the second time. Again we cried for medicals. Luke came back and it was then he told me he had dressed Sherley so we got him away. I then put a dressing on Trimble who gave all possible assistance, finally leaving by his own power. We then disposed of the Tel. who I realised was now dead. I then turned to Shaw who was still sitting on his knees all though. Rogers said to me “he’s dead, sir. He’s still” and gave me a hand to get the bodies away.

Ordinary Seaman Ian William Grant

Service No. 1734

Age: 18

Born 25 November 1921 joined the seaman branch at HMS Philomel on 15 June 1939. After his initial training he was posted to HMS Achilles on 26 August 1939 just before she departed New Zealand for her deployment to the South Atlantic as per the orders of the Admiralty. This was his first and only sea posting. His posting record card shows his next of kin located in Dunedin but does not note his place of birth.

During the battle he was serving on the one of the port 4-inch guns when a splinter from a near miss struck him and caused mortal injuries. Able Seaman Huia Beesley was manning a four inch gun on the port side of Achilles when the near miss occurred:

Unfortunately young Ian Grant who was alongside of me copped it in the chest. He died immediately. A chap…dropped to the deck [wounded]…there was no use leaving him there, we couldn’t do anything as far as firing was concerned. I picked him up, threw him over my shoulders…to get him down to Sick Bay.[48]

He was buried at sea at sea at 1000 on Thursday 14 December 1939. His name is recorded on the Memorial to those New Zealanders killed in naval service during the Second World War with no known grave located at HMNZS Philomel the main naval base at Devonport, Auckland.

Ordinary Telegraphist Neville ‘Jack’ Jervaise Millburn

Service No. SX23288

Age 19

Neville Milburn was a rating on loan to the NZ Division of the Royal Navy. He was serving in the Director Tower when it was struck by splinters by a near miss from one of Graf Spee’s 11-inch shells. He was one of two telegraphists serving in the Director Tower when he was killed at his post when struck by a splinter. He was buried at sea on 14 December 1939 but sadly his body washed up on shore and was buried at the Buceo British Cemetery, Montevideo Grave SC 225 with Frank Stennett.

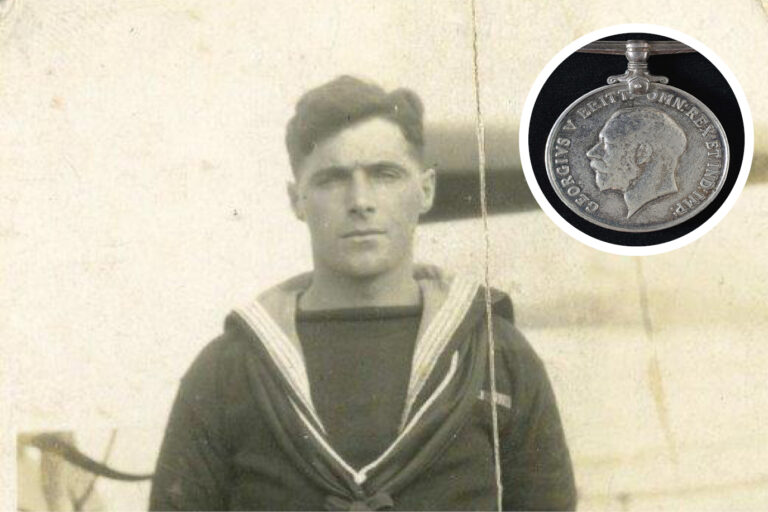

Able Seaman Archibald Cooper Hirst Shaw

Service No. 1030

Age 27

Archibald Shaw joined the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy in 1929 and was sent for training as a Boy Seaman to Philomel on 22 February 1929. On 17 October 1930 he signed on for a twelve year engagement. During his service he served in the cruisers HMS Dunedin, Diomede and Leander. After training at HMAS Cerebus in Australia he returned to New Zealand and was posed to Achilles in December 1937 as an Able Seaman. He was serving in the Director Tower operating the sight setter ranging equipment that controlled the fire of the six-inch guns and was struck by splinters from the near miss that also killed Millburn and Stennett and died of multiple injuries to his chest. His next of kin was his mother in Petone, Wellington. He was buried at sea at 1000 on 14 December 1939.

Shaw telegram 16/12/39:

Much regret to inform you that Able Seaman A.G.H. Shaw was killed in the action between HMS ACHILLES and German Battleship GRAF SPEE. The Government extend their deepest sympathy.

Galley & Thomas telegram 16/12/1939

I desire to express on behalf of the Government and myself deepest sympathy in the loss of your son whose life has been so nobly sacrificed in the service of the British Commonwealth.

Telegraphist Frank ‘Snowie’ Stennett

Service No. JX 148899

Age 18

Frank Stennett the son of Frank and Jessie Stennett, of Hazel Grove and stepson of Eveline Stennett, of Hazel Grove, Greater Manchester. He, like Millburn was a rating on loan to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy. He was one of two telegraphists serving in the Director Tower when it was struck by splinters by a near miss from one of Graf Spee’s 11-inch shells. He was killed at his post when struck by a splinter. He was buried at sea in 14 December but sadly his body also washed ashore was buried with Millburn at Buceo British Cemetery, Montevideo in grave SC225. [see image below]

N Series 1 Box 419 13/33/10 Personnel: War Casualties HMNZS Achilles in Action with Graf Spee

Letter to Grant Thomas mother dated 29/12/1939 from Naval Secretary

Advised that her son was buried at sea on Thursday 14 December 1939

Letter to M I Sherley 29/12/1939

Advises that AB Sherley transferred to Falkland Islands hospital after being wounded at the battle – making satisfactory progress

All wounded wound up at Falkland Islands – Martinson

Relatives of the four men killed were telegrammed from the Minister of Defence on 15 December 1939 followed by letter dated 16/12/1939

“They [the Naval Board] feel, however, that it will be some consolation to you in your loss that your son, …., lost his life while engaged in a most gallant naval action which has stirred the world, and of which the New Zealand Naval Forces in particular have the greatest reason to be intensely proud.”

I am, dear Sir, Yours most sincerely

N T P Cooper Naval Secretary

Same letter for wounded changed to

“Was wounded his life while engaged in a most gallant naval action which has stirred the world, and of which the New Zealand Naval Forces in particular have the greatest reason to be intensely proud.”

Shaw telegram 16/12/39

“Much regret to inform you that Able Seaman A G H Shaw was killed in the action between HMS ACHILLES and German Battleship GRAF SPEE. The Government extend their deepest sympathy.

Galley & Thomas telegram 16/12/1939

I desire to express on behalf of the Government and myself deepest sympathy in the loss of your son whose life has been so nobly sacrificed in the service of the British Commonwealth”

Those wounded telegrams said the Government extend their sincere wishes for his speedy recovery.

Two of he first telegrams dated 14/12 & 15/12 reports four killed and 3 seriously wounded. But 14/12 reports Admiralty did not get the information until 15/12 but all names were not reported.

Bibliography

Bekker C., Hitler’s Naval War, Macdonald, London, 1974.

Grove E., The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2000.

Hinsley F.H., Hitler’s Strategy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1951.

Parry W.E., Captain Parry’s Story of the Battle, reprinted from the Auckland Star, February 23, 1940.

Pope D., The Battle of the River Plate, William Kimber, London, 1956.

Von der Porten E.P., The German Navy in World War II, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, 1969.

Raeder E., Struggle for the Sea, William Kimber, London, 1959.

Roskill S.W., History of the Second World War: The War at Sea, vol. 1, HMSO, London, 1954.

Ruge F., Der Seekrieg: The German Navy’s Story 1939 – 1945, United States Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1957.

Var., Battle Summary No. 26: The Chase and Destruction of the “Graf Spee” 1939, Including the Battle of the River Plate 13th December 1939, Tactical, Torpedo and Staff Duties Division (Historical Section) Naval Staff, Admiralty, London, November 1944.

Var., Review of Damage to His Majesty’s Ships (3rd September 1939 to 2nd September 1940) : With accounts of damage received by HM Ships EXTETER, PUNJABI, SUFFOLK, NELSON, BARHAM, KELLY and FIJI, Naval Equipment Department, Admiralty, London, February 1941.

Waters S.D., Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War: Royal New Zealand Navy, War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1956.

Waters S.D., Operations of HMS Achilles August 1939 – February 1940, War History Narrative, Wellington c1946.

References:

[1] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 3-6.

[2] ibid. pp. 8-9.

[3] ibid. p.12, 33.

[4] F.H. Hinsley, Hitler’s Strategy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951, pp. 2, 5.

[5] E.P. von der Porten, The German Navy in World War II, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1969, p. 21.

[6] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, p. 15. For a fuller discussion of this review see C. Bekker, Hitler’s Naval War, London: Macdonald, 1974, pp. 28-35.

[7] Battle Summary No. 26: The Chase and Destruction of the “Graf Spee” 1939, Including the Battle of the River Plate 13th December 1939, London: Tactical, Torpedo and Staff Duties Division (Historical Section) Naval Staff Admiralty, November 1944, pp. 1-2.

[8] C. Bekker, Hitler’s Naval War, London: Macdonald, 1974, pp. 17-19.

[9] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 16, 25.

[10] ibid. p. 24.

[11] S.D. Waters, Operations of HMS Achilles August 1939 – February 1940, War History Narrative, Wellington c1946, pp. 2-5.

[12] Battle Summary, pp. 2-3.

[13] ibid., p. 3.

[14] S.D. Waters, Operations of HMS Achilles August 1939 – February 1940, War History Narrative, Wellington c1946, pp.18, 25.

[15] Battle Summary, pp.7-8.

[16] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, p. 25.

[17] ibid. pp. 26-27.

[18] Battle Summary

[19] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, p. 35.

[20] ibid., pp. 52-53.

[21] Battle Summary, p. 10.

[22] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 53-54.

[23] ibid. pp. 54-55.

[24] Battle Summary, p. 24.

[25] W.E. Parry, Captain Parry’s Story of the Battle, reprinted from the Auckland Star, February 23, 1940, p. 9.

[26] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 67-69.

[27] ibid., pp. 69-70.

[28] ibid., pp. 70-71. The ranges are taken from the Battle Summary, Plan 4A.

[29] ibid., pp. 73-76.

[30] ibid., pp. 78-79.

[31] ibid., pp. 80-82. That the practice round was fired by ‘B’ turret is from a member of the turret’s crew, R. Olausen.

[32] ibid. p. 84.

[33] Battle Summary, p. 29

[34] ibid, pp. 82, 86, 88, 105. Another critical element of damage revealed in Montevideo was the fact that some of the main engine cylinders were cracked and piston rods out of alignment, reducing the ships maximum speed to 17 knots.

[35] Battle Summary, pp. 30-31.

[36] The clause stated that if a merchant ship of a belligerent sailed from a neutral port, a warship of the other side could not sail for 24 hours

[37] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 96-115.

[38] ibid., pp. 116-119. The comment is from an interview with an officer from the Graf Spee, in the BBC TV documentary The Battle of the River Plate, 1979

[39] ibid., pp. 122-132.

[40] S.D. Waters, Operations of HMS Achilles August 1939 – February 1940, War History Narrative, Wellington c1946, p.149.

[41] E. Grove, The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000, pp. 137-139.

[42] ibid., pp. 109, 129.

[43] D. Pope, The Battle of the River Plate, London: William Kimber, 1956, Appendix F.

[44] Grove pp 134, 148-149; The Weekly News, 28 February 1940, p12

[45] Grove pp156-163

[46] S.D. Waters, Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War: Royal New Zealand Navy, War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1956, pp. 68-72.

[47] Personnel: War Casualties HMNZS Achilles in Action with Graf Spee: N Series 1 Box 419 13/33/10

[48] DLA 0010 H.H. Beesley Oral History, Auckland: RNZN Museum, September 1990, p. 14.