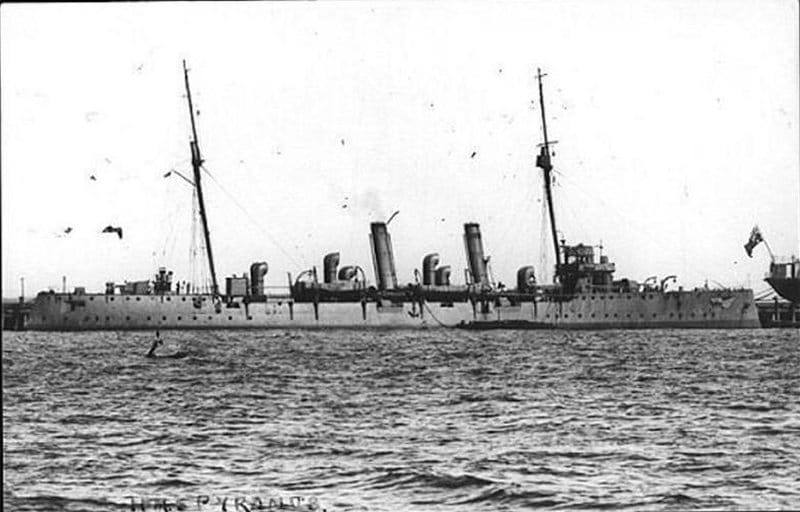

New Zealand’s close association with Western Samoa began in 1914 when the then German colony was occupied by an expeditionary force from New Zealand. Part of the escort for this expedition was New Zealand’s only warship, HMS Philomel.

One of the first engagements of World War One that involved New Zealand was the capture of German Western Samoa.

Within days of the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, Britain requested of New Zealand “a great and urgent imperial service,” the seizure of the new German radio transmitter recently installed in the hills above Apia in Western Samoa.

New Zealand was quick to oblige and within ten days had despatched an Expeditionary Force of some 1400 troops on ships requisitioned from the Union Steam Ship Company.

The Monowai and the Moeraki escorted by the ageing cruisers of the New Zealand Division, HMS Philomel, Pyramus and Psyche, were sent to capture the German-owned islands.

This expedition was primarily to neutralise the German global radio transmission network which was capable of long-range radio traffic to Berlin.

The transmitters in the Pacific were vital to the German East Asiatic Squadron based in Tsingtao in China under Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee.

Australia had been asked to do a similar job in New Guinea and Nauru.

In addition to converting the use of the wireless station from Germany to Britain, the occupation would serve to protect trade routes in the South Pacific and might draw the German Cruiser Leipiz from the coast of South America.

The troops embarked in the transports on 12 August but their departure was delayed because of the necessity to provide an adequate naval escort.

The positions of the German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were not known and the Australian Squadron was required to supplement the escort.

A telegram had been sent by the New Zealand Government to Rear Admiral Patey, the Commander of the Australian Fleet advising him that the occupation force was ready to start and asking if the route was safe.

This message was received by Admiral Patey on the night of 12/13 August and was the first that he had heard of the expedition.

He had at that time, just completed searching for the German squadron in the vicinity of New Guinea and Nauru and anticipated that the enemy would be moving eastwards across the Pacific.

Accordingly, he replied that an escort much stronger than the three ‘P’ Class cruisers was essential and made arrangements to meet the expedition off Suva, subsequently changed to Noumea.

At Noumea the ships met Rear Admiral Patey with the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the cruiser HMAS Melbourne and the French cruiser RFS Montcalm.

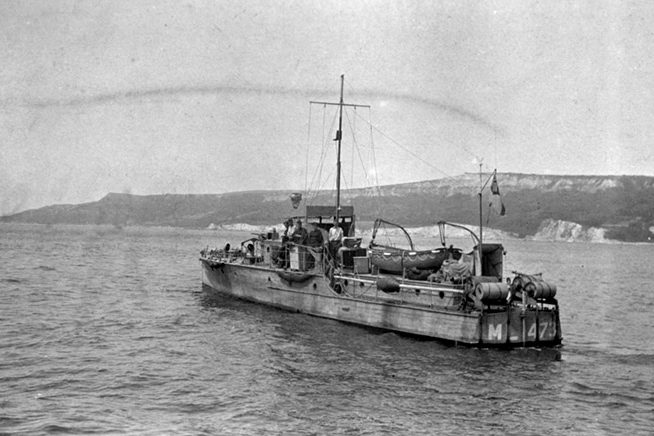

With the escort now suitably reinforced the expedition sailed for Samoa, via Fiji, and arrived off Apia on 29 August. At 8.00am Psyche sent a boat ashore under a flag of truce with two officers and an ultimatum for the Governor.

In the absence of the Governor the Chief Justice received the officers and advised that while he had no authority to surrender, he had issued orders that there would be no opposition and that no mines had been laid in the harbour.

Two picket boats from Australia swept the channel as a precaution before the transports entered.

The Union flag was hoisted at 12.45pm and the landing of the troops commenced at 1.00pm.

At 8.00 am on Sunday 30th August the British Flag was hoisted over the Courthouse and a proclamation read by Colonel R. Logan ADC, NZSC, the Officer Commanding the Troops, in the presence of Naval and Military Officers and men, Native Chiefs and the residents of Apia.

A salute of 21 guns was fired by Psyche.

At midday Australia, Melbourne and Montcalm sailed and later that day the transports, with the late Governor and other prisoners of war, departed for New Zealand escorted by Psyche and Pyramus.

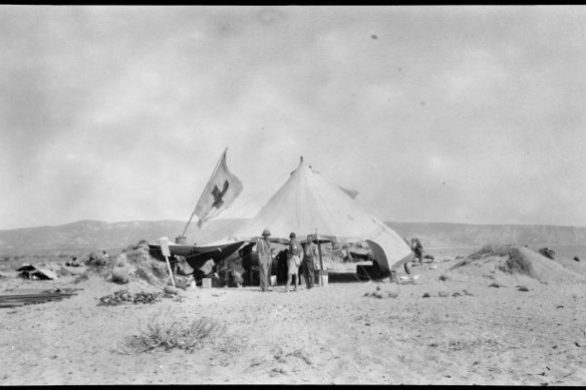

The wireless station had been put out of action by the Germans and although it was anticipated that it could be (and was) made operational again, it was decided to erect a wireless installation that had been brought with the troops.

This task was allocated to Philomel and necessitated the ship remaining some hours after the other ships departed.

Having erected the wireless equipment Philomel sailed for Pago Pago in American Samoa on the 31st to inform the Authorities there of the occupation.

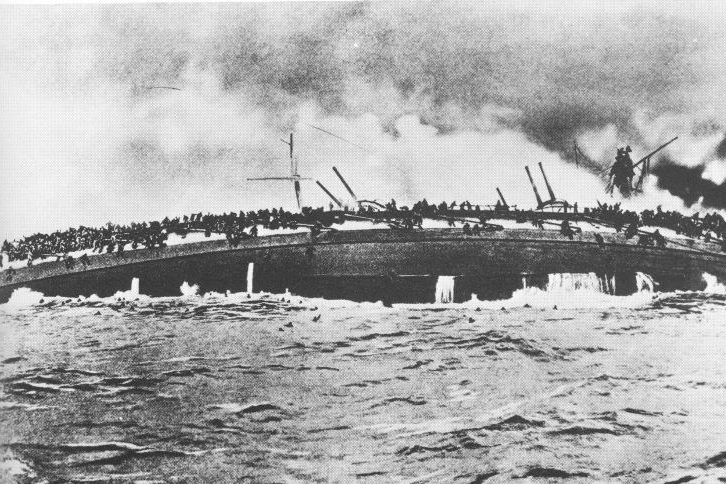

The threat from German warships was still present and on 14 September Admiral von Spee, with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau appeared off Apia.

Although the two ships came close up to the harbour, no attempt was made to communicate with the shore or to land. Despite expectations of bombardment the ships eventually moved off without firing.

This quiet visit resulted from there being no warships left to guard the port and von Spee’s ships not being able to land a sufficiently strong landing party.

Additionally he had no desire to waste ammunition or damage German property by a bombardment.

New Zealand’s response to a request from the Imperial Government began this country’s connection with Samoa and it was quite appropriate that the country’s only warship was involved in this enterprise, the first Expeditionary Force despatched by New Zealand in the Great War.

Although Philomel was a small part of the larger naval force, it was part of a national enterprise, in a manner that was not again possible until acting as a depot ship for the sweeping of mines off the New Zealand coast, at the end of the war.