As part of the effort to combat the submarine menace during the First World War the Royal Navy built 550 motor launches and 124 coastal motor boats. The officers and motor mechanics for these vessels largely came from the Royal Naval Motor Boat Reserve. Around 200 New Zealanders served in the Royal Naval Motor Boat Reserve.

In February 1915 as part of the anti-submarine programme, it was decided to build a large number of anti-submarine motor launches in the then neutral United States.

An initial order for 50 vessels of 75 feet in length was placed on 9 April and a supplementary order for an additional 500 vessels, 80 feet in length, was placed on 9 July, with a final delivery date of 15 November 1916.

Without work on Sundays, this allowed 501 days to build the 550 vessels.

To avoid compromising the neutrality of the United States the orders were placed through Canadian Vickers, on Elco at Bayonne, New Jersey.

Canadian Vickers fabricated the components, which were then sent to Montreal for assembly. The last of the launches was delivered on 3 November 1916. Forty vessels were transferred to the French Navy.

Both types of vessel were essentially identical in characteristics. They were powered by two 440 hp petrol engines which enabled a top speed of 19 knots. Forward was mounted a 13 pounder gun (soon replaced with a 3 pounder) and two depth charges. Additional armament consisted of lance bombs and a Lewis machine gun. The crew comprised two officers, two motor mechanics two leading seaman and four seamen. One of the seamen was detailed as the cook. Most of the officers and motor mechanics were from the Royal Naval Motor Boat Reserve.

The depth charges were iron drums containing 150 pounds (68 kg) of explosive, activated at a pre-determined depth.

Lance bombs were grenades, resembling pineapples on the end of a broom stick. Oscar Carter, a New Zealand officer, later recalled that he was unable to determine how these could be used without eliminating the user.

The prime means of detecting a submarine was a visual sighting, but there was also a hydrophone. New Zealand physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford played a key role in the development of the hydrophone.

This was a passive listening device which could hear the engines of a submarine.

To use the hydrophone it was necessary for the boat to stop and lower the device over the side of the vessel.

By the sound received it was possible to determine the type of engine and the direction in which the vessel using the engine lay.

There was no means of determining distance. Each ML (Motor Launch) had two seamen trained in the use of the hydrophone.

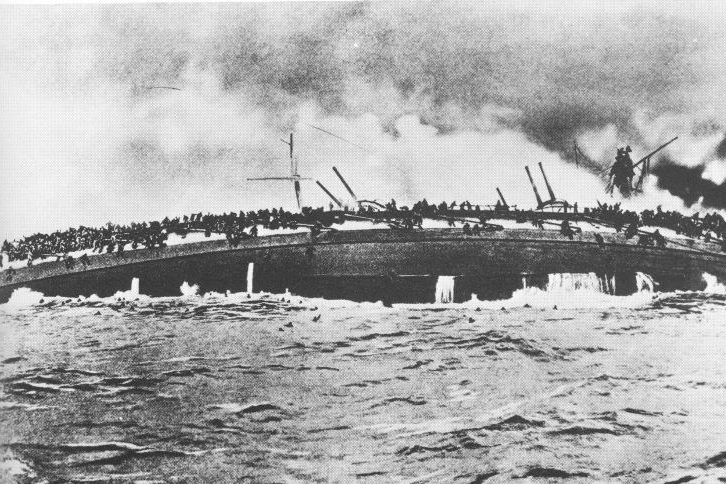

While generally satisfactory the vessels were not without their defects. Their size was relatively small which affected their seaworthiness. The most dangerous defect was the Hall-Scott petrol engines. Petrol poses a very real fire hazard. Problems with the engines overheating resulted in a decision in mid-1916, to use a mixture of one part petrol to two parts kerosene. Another challenging feature of the engines was that they had to be stopped and restarted when going from ahead to astern (backwards) or vice versa. This resulted in some spectacular incidents because the engines were started with compressed air and there was the occasional failure of the engines to restart when manoeuvring.

In contrast with the slow, defensive nature of the Motor Launches were the Coastal Motor Boats, known as CMBs. In mid-1915 the ship building firm of Thornycroft submitted a plan for a small fast motor boat capable of carrying a torpedo. Three naval officers were seconded to Thornycrofts to assist in developing the design which had to be as light as possible, no more than 30 foot long, capable of being carried in davits (lifting and launch system), on a light cruiser and with a speed of not less than 30 knots.

It was quickly realised that launching the 14 inch torpedo by dropping gear was not practical, however an alternative of launching the weapon, tail first, over the stern seemed possible. It was essential, however that the boat be going at about the same speed as the torpedo, in order that it could be steered clear of the torpedo’s track. Following successful trials and completion of the design, orders were placed for 12 boats in January 1916, the first three being completed in April. These were 40 foot long and secrecy was such that they were built on an island in the Thames with trials being conducted at night. The total crew comprised just two officers. The first vessels had a top speed of just under 25 knots, however later boats were able to achieve around 37 knots. Fifty-two of these boats were built.

While this boat was being developed Thornycrofts were designing a larger vessel capable of carrying two torpedoes. After trials this 55 foot boat was accepted for service in mid-1916, although the torpedo outfit had been reduced to one, with four depth charges replacing the other torpedo. There were several variants of the basic design, officially distinguished by letter suffixes, 72 boats were built. Depending on the type of engines, they were capable of speeds between 35 and 41 knots. The 55 footers had a crew of two officers, two motor mechanics and a wireless operator.

Despite their obvious offensive capabilities the primary function of the CMBs was anti-submarine. For this function they were based at Dover, Portland and Portsmouth and later at Dunkirk.