The campaign against Turkey in the eastern Mediterranean was one of the most ill-conceived campaigns of the First World War.

It arose out of a desire to open operations beyond the Western Front in France and relieve pressure on the Russians in the Caucasus.

From a purely naval operation to force the Dardanelles on the western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula it developed into a land operation thrusting up the length of the peninsula, costing over 130,000 lives.

As 1914 progressed to a deadlock on the Continent, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill was impatient to see a naval victory.

He was dismayed at the apparent lack of action on the part of the Grand Fleet, not appreciating one of the basic principles of sea power; control of the sea.

With the Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow, the German High Seas Fleet could not leave its base without a major engagement with its numerically superior enemy and thus the Grand Fleet had control of the sea.

Nevertheless beyond Churchill there was a desire to see the new armies that were now coming into being, used for projects other than “to chew barbed wire in Flanders”.

In early January 1915, Russia appealed for help to relieve pressure on Turkish assaults in the Caucasu.

The First Sea Lord, Admiral Fisher and Major Maurice Hankey, Secretary of the War Cabinet presented a proposal for an attack on Gallipoli by Greek and Bulgarian troops (despite both countries being neutral at the time) backed by Indian troops and 75,000 troops from the Western Front.

At the bottom of this memo was a comment to the effect that the Navy would use obsolete battleships to force the Dardanelles. The objections by the Army to this plan were numerous.

Churchill seized on the last point, a naval assault through the Narrows into the Sea of Mamora and on to Constantinople (now Istanbul) which would provide the naval offensive he had been seeking.

Admiral Carden, the Chief in Charge Eastern Mediterranean was consulted. He was not one of the brightest admirals and responded to the effect that the operation was feasible and how he would go about the task.

With the need to “do something” and Churchill’s infectious enthusiasm the plan was approved.

This was despite Nelson’s admonition that “any sailor who attacks a fort is a fool” (he lost an arm at Tenerife) and the fact that Admiral Phipps Hornby had written a long and reasoned appreciation on ‘why he should not to be asked to force the Dardanelles’ in 1895.

Cabinet authorised the use of 15 battleships, including the latest, HMS Queen Elizabeth armed with 15 inch guns and three battlecruisers.

By mid-January Fisher and all of the sea lords were opposed to the plan, but could not prevent it going ahead.

At 9.51am on 19 February the first shot was fired. Spotting aircraft from HMS Ark Royal had a splendid view of events, but whose spotting corrections were ignored.

Lieutenant Williamson, one of the spotters flew low over the Turkish forts and noted that no damage had been done to any of the guns.

When he reported in person to Admiral’s Flag Commander and the Chief of Staff, Commodore Keyes, he was not well received and the Commodore became very indignant when told that the ships had hit nothing.

Inclement weather precluded further bombardments for the next five days, but when it cleared the bombardment resumed.

With much dust and rubble resulting from the shell blasts, it seemed, the Admiral reported, that it was impossible that all the forts and guns had not been destroyed.

With the significant aid of Queen Elizabeth’s 15 inch guns the outer forts were eventually silenced.

The next part of the operation required entering the Narrows where there were minefields, covered by minefield batteries which were in turn covered by the forts and also mobile howitzers.

Several attempts were made to sweep the minefields but all had to be abandoned under heavy, close range fire. On 10 March an unsuccessful attempt was made to engage the forts in the Narrows, while on the same day in London, the terms for the Turkish surrender were being considered.

Further attempts to sweep the minefields were not successful, their protection being most effective.

An ill and dispirited Admiral Carden resigned on 16 March, being replaced by Admiral De Roebeck, ‘worth a dozen of Carden’ in the view of the commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), General Birdwood.

Admiral De Roebeck made a serious attempt to force the Narrows on 18 March with eight battleships.

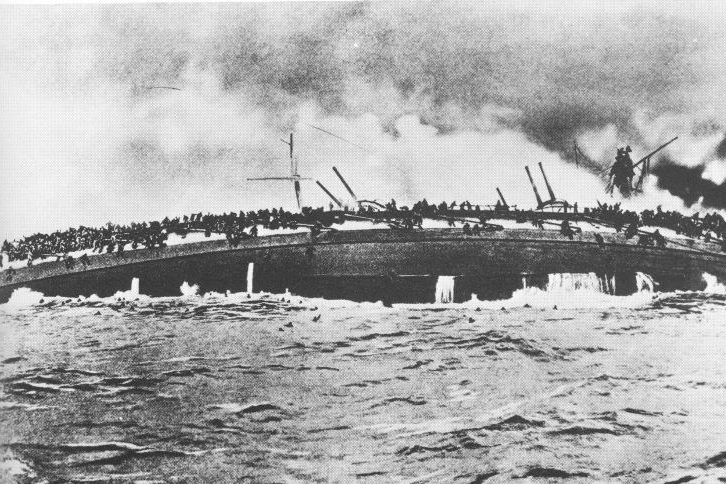

The French battleship Bouvet struck a mine and sank with most of her crew and the battlecruiser Inflexible also struck a mine and was put out of action for several weeks.

The battleship Irresistible struck a mine and sank during the night as did the battleship Ocean when it went to the aid of Irresistible. Admiral De Roebeck then cancelled the operation.

Even before the first shot had been fired the necessity of providing land support to the naval operation had been considered, but deferred.

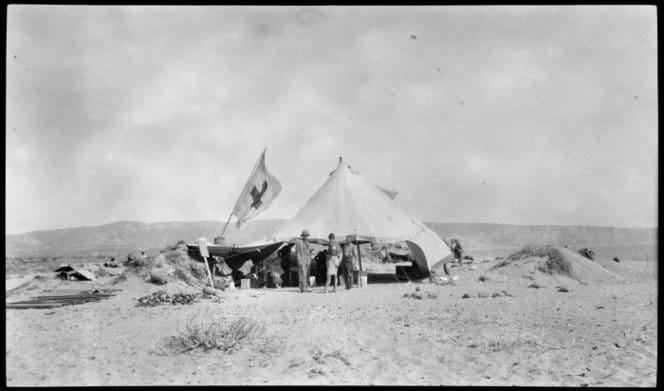

Now, in an effort to prevent ‘a severe loss of Allied prestige’, the Army was to join in the operation. Meanwhile the Turks had significantly increased the number of troops on the peninsula.

The allied landings on 25 April 1915 were the precursor to the deaths of more than 130,000 men (including 2,770 New Zealand, 8,709 Australian and 86,692 Turkish) and the reputations of many.

The naval participation in the Gallipoli campaign did not cease with the landings. Throughout it provided support to the troops ashore, both logistical and fire support and submarines regularly negotiated the Narrows and operated in the Sea of Mamora.

The Royal Naval Division fought ashore as did RNAS Armoured Cars and aircraft of the RNAS provided reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

On 12 August 1915 Lieutenant Charles Esmond operating from the seaplane carrier Ben-my-Cheree sank a Turkish ship in the Sea of Mamora, the first to be sunk by a torpedo launched from an aircraft.