New Zealand made a worthy contribution to the naval war of 1914 – 1918. Given the small size of the country it is a contribution of which we can be proud.

From Admiralty to Navy Wellington 11/11/18

Now that the last and most formidable of our enemies has acknowledged that triumph of the Allied Fleet and troops on behalf of right and justice I wish to express my praise and thankfulness to the officers, men and women of the Royal Navy and Marine and their comrades of the Fleet Auxiliaries and Mercantile Marine, who for more than four years have kept open the seas, protected our shores and given us safety. Ever since that fateful 4th August 1914 I have remained steadfast in my confidence that the Royal Navy would once more prove the sure shield of the British Empire in the hour of trial. Never in its history has the Royal Navy with God’s help done greater things for us nor better sustained its old glories and chivalry of the seas. With full and grateful hearts the peoples of the British Empire salute the White, the Red and the Blue Ensigns and those who have given their lives for the flag. I am proud to have served in the Navy and I am prouder still to be its head on this memorable day.

George R.I.

HMS Philomel

When war broke out in 1914 New Zealand was still very much attempting to determine the most appropriate forces necessary for the defence of the country. This was even more evident in respect of naval defence. The New Zealand Naval Forces had been established under the Naval Defence Act of 1913 and would be supported by the New Zealand Division of the China Station, comprising HM ships Psyche, Pyramus, and Torch, based at Auckland. HMS Philomel was commissioned for service under the New Zealand Government on 15 July 1914, under the command of Captain Percival Henry Hall-Thompson RN, who was also Naval Adviser to the New Zealand Government.

HMS Philomel was a third-class cruiser of the ‘Pearl’ class which had been laid down at Devonport Dockyard, England, on 9 May 1889. Of 2,575 tons, 265 feet in length, armed with eight 4.7 inch guns, eight 3 pounder guns and four 14 inch torpedo tubes, Philomel had a speed of 17 knots. The ship was commissioned on 10 November 1891 and spent the majority of the next 21 years around Africa.

At the commencement of hostilities, Philomel was placed under the operational control of the Senior Officer of the ‘New Zealand Division’. The first offensive action taken by New Zealand at the outbreak of the war was, at the invitation of the Imperial Government, to occupy German Samoa. A composite force was raised from the Dominion and sailed from New Zealand escorted by the cruisers of the New Zealand Division; including Philomel. After this, the next major employment for the ship was as an escort for the troopships conveying the main body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to Egypt. At Albany, Philomel left the troopships and spent the next two years serving with the Royal Navy in the Middle East. She initially served in the eastern Mediterranean, where a landing party from the ship encountered Turkish Forces and sustained New Zealand’s first naval casualties. In the main, however, Philomel spent the war in the Persian Gulf. For a short time during 1916. Generally operations in the area comprised keeping the peace and maintaining a British presence. Captain Hall-Thompson was Senior Naval Officer in the area for much of 1916.

By the end of 1916, it was apparent that Philomel was in need of a major refit. There was considerable discussion as to the value of spending a large sum of money on such an old ship. Philomel returned to New Zealand to pay off to become a depot ship, under a care and maintenance party. The ship’s armament was removed and fitted on Defensively Armed Merchant Ships.

New Zealand Volunteers

With only a single cruiser comprising the New Zealand Naval Forces, the majority of New Zealanders who wished to serve at sea during the war were compelled to join the Royal Navy. Simply having a desire to join the navy was not enough if you were a New Zealander during WWI. With the Army in charge of the Defence Department, men of military age could not leave the country for naval service unless they had prior approval from the Headquarters New Zealand Military Forces. This effectively precluded recruiting men for service in the Royal Navy in New Zealand.

One significant group in this latter category were the nearly 200 men who volunteered for service in the small vessels of the Motor Boat Patrol. Although technically Royal Naval personnel, those who joined for the period of hostilities were not forgotten by the New Zealand Government, which topped up the pay of married men to the level being received by equivalent ranks of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. These men, and at least two women, were from varied backgrounds. They were involved in virtually every aspect of the war at sea between 1914 and 1918, and indeed, some even served in the Allied intervention against the Bolsheviks in Russia during 1919. They were at sea with the Grand Fleet, in the Air with the Royal Naval Air Service, beneath the waves in submarines and as Chaplains and Wrens.

The Motor Boat Reserve was one of the responses to the very real threat to the survival of Britain posed by German submarines. In mid 1916 a small Royal Navy team arrived in New Zealand to recruit officers and motor mechanics for the Reserve, having previously recruited personnel in Canada. This recruiting tour received unique exemption from the normal prohibition of men being allowed to leave the country to enter naval service.

A number of the New Zealanders serving in the Motor Boat Reserve distinguished themselves in action. In particular there were a number involved in the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend in April and May 1918, about a third of whom were decorated for gallantry. In the main, however; the work of the patrol was monotonously uneventful, albeit essential.

A few examples represent the variety of service experienced by New Zealanders and their contribution to the war effort. Alexander David Boyle, from Christchurch, was a regular Royal Navy officer who spent the war in the battle cruiser HMS New Zealand. Lieutenant Commander William Sanders RNR, from Takapuna, won the Victoria Cross serving in Q Ships and lost his life in this third encounter with a submarine. Sub Lieutenant Frederick Manning joined the Royal Naval Air Service and became an Observer. Miss Enid Bell from a prominent Wellington family became one of the first women to join the newly established Women’s Royal Emergency Naval Service in 1917.

Enemy on our doorstep

While the main thrust of the war was in Europe, it is often forgotten that hostilities were brought to New Zealand’s door step in 1917. In June of that year SMS Wolf laid mines in the shipping lane to the immediate north of the country and in the approaches to Cook Strait. Disposing of this menace, which claimed two ships, was another vital part of the war at sea. With no minesweepers in New Zealand, two trawlers, Nora Niven and Simplon, were chartered and converted for minesweeping using equipment manufactured locally. Working as a pair with naval personnel providing guidance, these vessels accounted for all of the mines swept in the two fields laid by Wolf. Later a third trawler, Hananui II, was fitted with special deep water sweeping gear and worked on the northern field. Some mines were washed ashore. Several broke free from their moorings and simply disappeared into the Pacific.

New Zealand’s contribution

Less visible contributions to the war at sea were also made by New Zealand. A major effort was in the provision of coal for naval ships. Westport coal was ideal for such purposes, unlike, for example Australian coal which burned at too high a temperature, causing damage to the interior of ships’ boilers. New Zealand’s coal output was largely exported for naval use resulting in a lack of supply on the domestic market and coal having to be imported from Australia.

A Naval Intelligence Centre was established in Wellington reporting direct to the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board in Melbourne, but also providing information to Esquimalt and the Cape of Good Hope as necessary.

The New Zealand marine radio stations were integrated into the Royal Navy’s world wide network, with operators being trained in naval procedures and keeping a listening watch for enemy signal traffic. With the occupation of German Samoa the radio station at Apia joined this network and co-operation was also received from the French station at Papeete.

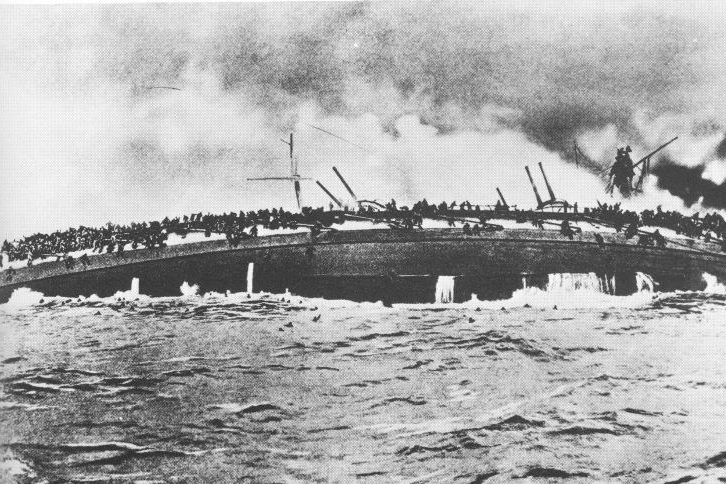

Although by no means a New Zealand Naval unit, HMS New Zealand was a ship of special importance to the people of this country. It had been gifted to the Royal Navy in 1910 and with a few New Zealanders on board, served with distinction in the Grand Fleet throughout the war. New Zealanders showed a special interest in ‘our gift’ battle ship and its activities were well reported.