All the artefacts in our collection tell their own story, or at least play a part in telling a much larger story. And sometimes we come across mysterious artefacts that force us to keep asking more questions, which, more often than not, remain unanswered. However, this isn’t always a bad thing. Even though we may not find out exactly what we are looking for, the research process can compel us to consider artefacts in a different context.

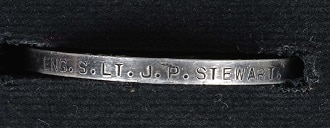

In April 2015 the Navy Museum was offered a single Victory Medal with the inscription ‘ENG SLT J. P. Stewart R.N.’

This medal had been handed to Mangere Police by a member of the public and was likely to have once been part of a common set of three medals issued to military personnel serving in World War One.

A decision was made to add the medal to our collection, it was catalogued and put into storage.

Fast forward to August 2016, the Navy Museum was once again offered a single medal.

This time it was the British War Medal, found by an observant Police Constable in the garden of the unlucky individual he was about to arrest (FYI – medal and arrestee were not connected, the situation was purely coincidental!).

Again we accepted the medal and added it to our permanent collection.

Joining the dots

It took a wee while for our Collections Assistant to join the dots, but eventually there came what we like to call a ‘museum moment’.

We now had two medals from the same WW1 naval officer, but they were no longer part of a set and both had ended up with the Police.

Then came all the questions … Who was ENG SLT J. P. Stewart? How did his medal set end up broken? Where was his 1914-1915 Star? And so the detective work began.

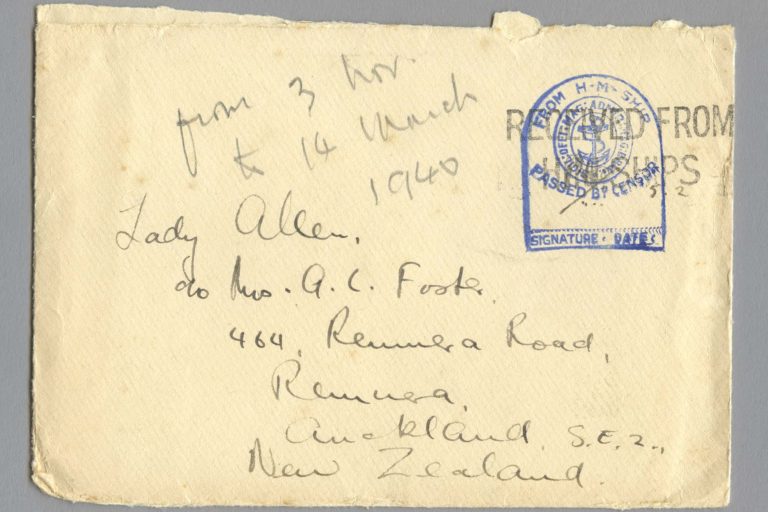

The starting point was an entry in the Otago Daily Times, 8 July 1919, mentioning an ‘Engineer Sub-lieutenant J. P. Stewart R.N., late of HMS Bellerophon’ arriving back in New Zealand with his wife on the troop ship Prinzessin.

This matched with records located by our Researcher who also discovered that J. P. came from Timaru.

There was a very good chance that this was our guy, so the next step was to try and find his service records.

An initial search gave hundreds of results for ‘J Stewart’ – that was about as helpful as a screen door on a submarine.

Finding a match

We needed a birth date and first names to be able to find any further information.

So we thought we would try our luck and do a general search for registered births in New Zealand between 1890 and 1900 (this would have put him within the enlistment age for WW1).

There were two possible results, a John Patrick Stewart and a James Patterson Stewart, one born in 1891 and the other in 1894.

These names went into the search engine of the National Archives UK and we got a result for James Patterson Stewart, Engineer Sub-Lieutenant, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

It seemed that we had found our medal recipient.

James Patterson Stewart was born on 1 February 1891, possibly in Timaru (not confirmed), to Agnes and James Stewart.

He was educated at South Timaru School and Timaru Boys High School before working for Messrs Parr & Co Engineering Services.

One of the documents we found referred to him being awarded the Merchantile Marine War Medal.

Combined with a note on his service record stating his 11 years previous experience at sea, this led us to believe that he started his war service as a civilian, or merchant, engineering officer. He would have transferred to an enlisted officer at some stage before 1916.

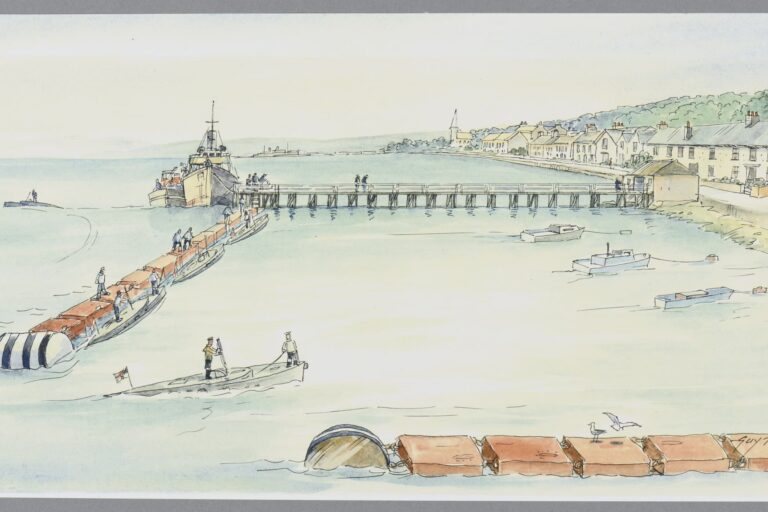

His first recorded postings as an enlisted Engineering Officer were circa 1916-1918 to HMS Virginian and HMS Nairana.

Virginian was an armed merchant cruiser, part of the 10th Cruiser Squadron that took part in North Atlantic convoys and patrols. Nairana was an Australian passenger ferry requisitioned by the Royal Navy and refitted as a seaplane carrier.

Excerpts from his service record describe him as ‘a zealous and promising officer’, with, ‘power of command and other officer-like qualities’.

From July 1918 – August 1918 Stewart was posted to the shore base HMS Victory where he undertook a series of engineering courses before posting to HMS Bellerophon.

This was his final posting of the war, he left Britain on the 16 May 1919 with his wife Jessie Black Stewart (nee Hamilton), arriving in New Zealand on 30 June 1919.

In 1920 James re-joined the Reserves, was promoted to Engineer Lieutenant in 1922 and remained a reservist until 1936 (when he was removed from the reserve list due to his age, he would have been 45).

The mystery continues

Then the information stops. We know nothing of his movements after 1936 or how his medals ended up in Auckland, broken and separated.

Did he sell them or did his family sell them after his death? Were they stolen from him or his family?

However, the one question we really want to know the answer to – where are the other two medals (1914-15 Star and the Merchantile Marine War Medal)?

Maybe they will turn up at another Auckland Police station and make their way to us.

We are probably never going to answer these questions. With further research it may be possible to pick up the trail of James and Jessie, or maybe not.

So, this leaves us with the story of the medals themselves and stopping to think about what objects mean to people.

Medals have always been, and always will be, objects with a lot of meaning.

They represent bravery, sacrifice, loss, and to some a romantic image of war.

To many people they are a symbol of remembrance to be treasured and passed down the generations.

To others they are highly collectible objects – one reason why they are so often the target of thieves.

So even though we haven’t been able to reunite these medals with the family of Eng. Sub-Lieutenant J. P. Stewart we can tell the story and take our turn as custodian, keeping them safe for future generations of New Zealanders.

by Caroline Ennen, Collections Assistant