Origins:

The use of flags, banners, standards or colours on the battlefield has a rich tradition that reaches back to ancient warfare. Such colours were a rallying point, a tool of leading men into combat, to mark the location of the HQ on the battlefield, and in the days when the monarch took the field with their army, their personal colour that followed him wherever they went on the field of battle showing their location. It would also fly from a castle if they were in residence. This practice continues to this day with HM Queen Elizabeth II.

It was only the onset of industrialised warfare in the 20th century that saw the elimination of colours on the battlefield and the restriction of their use to purely ceremonial purposes. National flags did retain some use on the battlefield and at sea as evidenced by the use of cloth flags or painted flags for identification purposes. For example, in Korea the top of the 4-inch gun shield fitted to the Loch-class frigates was painted with the British national flag as a way of identifying the warship to friendly aircraft.

Development:

With the rise of national armies in the 17th century a system of national flags was developed and nation-states established an identity. Each nation-state chose colours and other heraldic devices to add to their flag. Two examples suffice, the orange used by the Netherlands (from the House of Orange, the Royal Family), and the red, yellow & black that are now in the German national flag had its origins in the Germanic lands that were fused into a united Germany in 1871.

Alongside the national flag the development of the regimental system in European armies in the 17th century required a rallying point and also a way to differentiate between regiments on the field and in ceremonial situations. The solution was a flag that was known as the Regimental Colours. Every regiment had its own colour and was an intimate part of the regimental tradition and heritage. It was common for battle honours to be sewn on to the colour. Examination of British regimental flags is to see the military history of the United Kingdom over the past 300 years. Due to their very nature, Regimental Colours were constantly being replaced after destruction in battle. The most obvious example of the power of the regimental colour is the example from the 1879 Battle of Isandhlwana. Surrounded by the mass army of Zulus, remaints of the 1st Battalion of the 24th Foot rallied to their Colour and stood their ground until all were killed.[1]

Use of Flags

In an age without radio, telegraph or other methods of instant communication the flag became a method to lead, to communicate and in combat a rallying point. On the battlefield the commander would have his vantage point marked out by the national flag and his personal standard. Each regiment in his command would have their own standard carried into action alongside the national flag. It is important to remember that the national flag and regimental colour were equal value but the loss of a regimental colour would be cause for sadness and despair in the survivors of the regiment. In turn, capturing a regimental colour was seen as a worthy action and at the conclusion of a battle there would be a procession of captured colours. These would be treated as war trophies and taken back to the regimental depot or the monarch’s palace.

British regiments took into battle their Queen’s Colours (King’s). This was the Union Jack with the regiment’s number in the centre of the flag along with regimental devices. The Regimental Colour was cantoned with the Union Jack and the colour of the flag was the colour of the facings of that regiments. For example, the Buffs would have carried a buff-coloured flag into battle. Up to 1751 there were three per regiment. From then only two as each regiment in British service had two battalions. Note that the Royal Artillery has no Queen’s Colour as their guns are sufficient as a rallying point and the Rifle Regiment’s task was to act as scouts therefore there was no need for a rallying point. The ceremony of Trooping the Colour comes from the tradition of carrying the Regimental Colour and Queen’s Colour slowly along the formed lines of the regiment to impress them on the memories of the members of the regiment.[2]

Navy

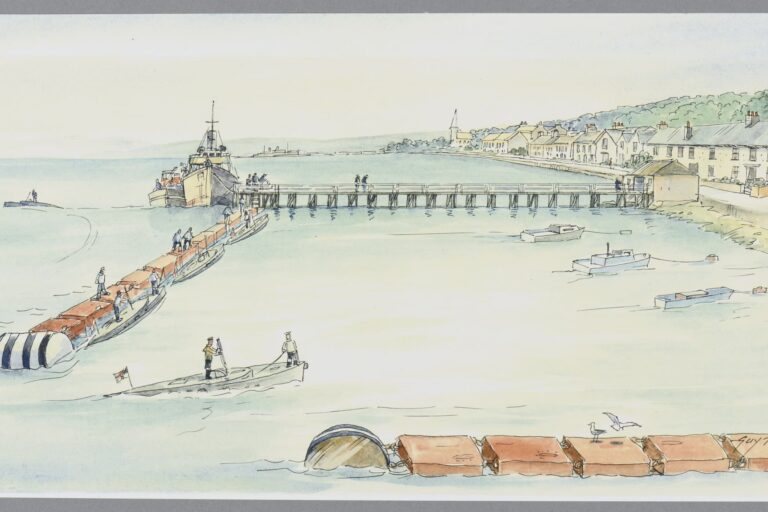

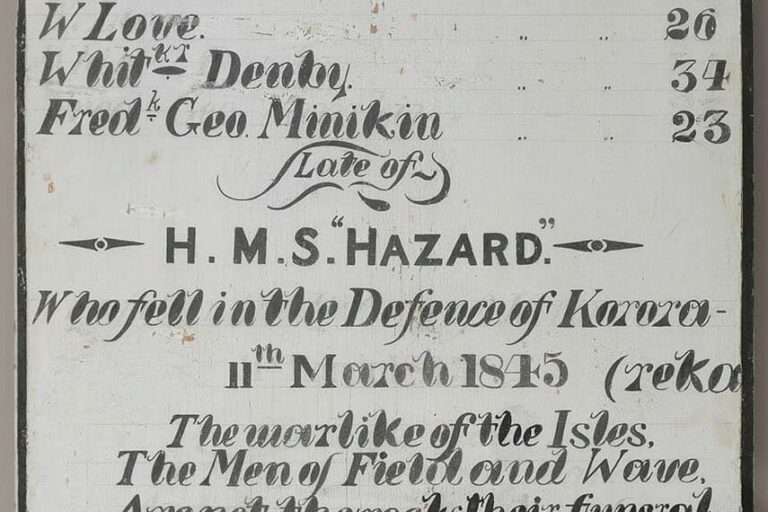

Regimental colours or standards did not find a place at sea. Ships carried ensigns for recognition and command purposes. In the 17th century, red, white and blue ensigns were carried by English warships show what squadron they were operating with. In addition to ensigns a range of pennants and flags came into use for recognition purposes that a senior officer was on board. For example in the 17th century when the monarch or Lord High Admiral was aboard a warship a flag known as the Royal Standard was flown from the mast. In 1702 it was regulated that only monarch could use the Royal Standard and could only be used when the monarch was aboard.[3]

Of course it was not until the 19th century that the White Ensign was formally designated to be carried by Her Majesty’s warships in 1864. Again as nation states developed, their national flag was carried by their warships. Battle ensigns were carried in the most prominent place for recognition purposes. In Royal Navy history this became the White Ensign from Nelson’s order at the Battle of Trafalgar that all ships in his fleet carry a white ensign at the main mast as a way of recognition during the confusion of ship to ship combat. In New Zealand’s history, the first time our national flag was carried into action as a Battle Ensign was at the Battle of Jutland by the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand. The second occasion was at the Battle of the River Plate when the Chief Yeoman of Signals got permission from the commanding officer Captain Parry to break out the New Zealand flag as a Battle Ensign.

One major difference between land and naval forces is the use of signalling flags. While the use of semaphore was common ashore, the navy developed a whole language built around signal flags. This began in the 18th century and still continues to this day and is a unique tradition in the senior service. The naval equivalent of colours would be the ship’s badge. Even though this was only a development of the 20th century, it has become an instant tradition and has assumed some of the role of a Regimental Colour for land forces but within a naval context.

Why the Queen’s Colour for the Navy?

Since a warship carries a White Ensign and the national flag there has been no need for a colour. However, because of the symbolism, heritage and military necessity of a formation being led by a colour bearer, the use of a monarch’s colour has come into use. It is clear that the Queen’s (or King’s) colour was created in the 20th century for ceremonial purposes only both aboard ship and ashore and perhaps recognition of the place of the Royal Navy as the Senior Service. Jane’s Dictionary of Naval Terms states that the Queen’s Colour is the ‘naval equivalent of [a] Regimental Colour.’[4] This would indicate that the purpose of the introduction of the King’s Colour in 1924 was for ceremonial purposes and recognition that the senior service did not use Regimental Colours and needed its own “Regimental Colour”. This was then extended to those Dominion navies that formed part of the Empire. In this however, we must be very careful not to use the term Regimental Colour. It is the monarch’s colour, and is only for ceremonial use on land or on ship and means that the senior service has a colour that can be honoured by our sister services in ceremonial occasions.

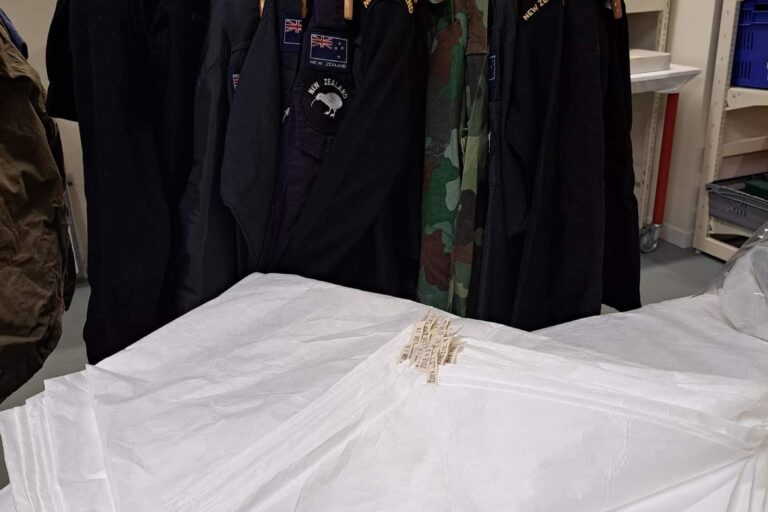

Dates of King’s (Queen’s) Colours presented for New Zealand Naval Service

1926 King’s Colour HM King George V

1936 King’s Colour HM King George V

1953 Queen’s Colour HM Queen Elizabeth II

1970 Queen’s Colour HM Queen Elizabeth II

1991 Queen’s Colour HM Queen Elizabeth II

[1] Thomas Harbottle, Dictionary of Battles, Rev. ed. by George Bruce, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1971, p. 135. See also A History of Warfare, London: Jane’s, 1982, pp. 443-459.

[2] Major Lawrence L. Gordon, Military Origins, Lieutenant-Colonel J.B.R. Nicholson (ed.), London: Kaye & Ward, 1971, p.38.

[3] John Hard, Royal Navy Language, Lewes: The Book Guild, 1991, p. 136.

[4] Joseph Palmer, Jane’s Dictionary of Naval Terms, London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1975, p. 190.