The Motor Launches acquired by the Royal Navy in 1916 had a large proportion of New Zealander’s as officers and motor mechanics.

These vessels formed part of the Auxiliary Patrol and were deployed around the British Isles and into the Mediterranean.

They performed a variety of tasks beyond that of anti-submarine patrolling for which they were originally acquired.

The acquisition of the Motor Launches was an anti-submarine measure and they were deployed in areas where German submarine activity could be expected.

On their coming into service the MLs were allocated to the various patrol areas of the Auxiliary Patrol.

Operating at sea was seldom pleasant. Certainly in fine summer weather conditions it was enjoyable, but in the main this was not the case.

Rough seas, high winds and lashing rain were not the only type of bad weather experienced but also snow, sleet and fog.

The usual rig was an oilskin in wet weather or duffel coat in dry, a woollen polo-neck jersey, trousers, thick socks and sea-boots.

On occasions, thick woollen trousers of the same material as the duffel coat were worn and said to give the impression of a boat manned by giant teddy-bears.

With the vessels being at sea most of the time, in all weathers, they were continually damp.

The different patrol areas provided different experiences. There were three patrol areas from Dunkirk, the West Roads, Hills Bank and Zuidcoote Pass patrols.

The West Roads patrol was essentially a straight line patrol about a mile off the harbour entrance, while Hills Bank was a similar but further to sea and more uncomfortable because it was outside the shelter of the sandbanks.

Zuidcoote Pass was considerably more dangerous, consisting of two MLs every night, keeping watch for enemy vessels leaving Ostend or Zeebrugge.

Operating off the Irish coast was different. Initially the main task was anti-submarine patrols, it being thought that German submarines could be using some of the small ports for replenishing.

This was later expanded to also counter the threat from Sinn Fein, the Irish nationalist organisation which had attempted to mount an armed insurrection at Easter 1916.

The main ML base was HMS Colleen at Queenstown (now Cobh), situated on Haulbwline Island in the middle of the harbour.

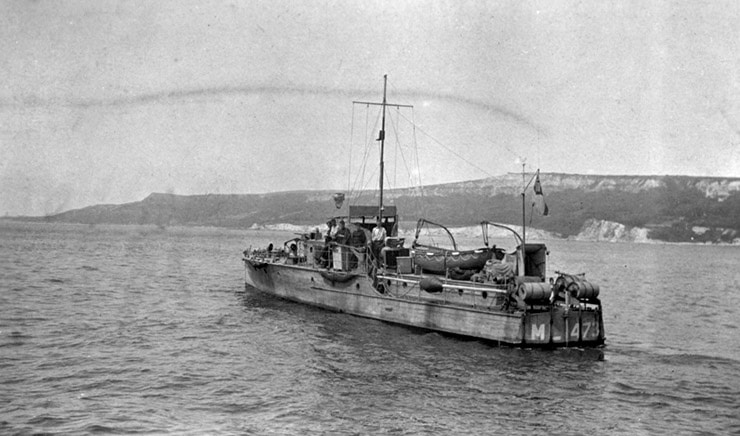

During 1917 there were two New Zealanders there, Sub Lieutenant Oscar Carter a ‘spare’ officer, relieving on various vessels as required and Motor Mechanic Clarrie Simpson in ML 487.

Because of their different operating routines they never met.

ML 487’s patrol area in mid-1917 was the South East coast, from Queenstown, to Rossmere, the usual routine being eight days on patrol and two days in Queenstown, with a four day spell in Queenstown every three months.

Different harbours and bays would be visited on each patrol. Without radio the MLs reported at the various coastguard stations which passed the information back to Queenstown.

In fine weather the MLs would usually anchor in the vicinity of a coastguard station overnight, conducting a hydrophone watch. In bad weather they would anchor in one of the small ports or bays for the night.

In their two days at Queenstown the ships would replenish with fuel, food and stores, complete any maintenance required and have a few hours leave.

Oscar Carter was involved in patrols against Sinn Fein as First Lieutenant of ML 374, one of several MLs, based at Galway, an outstation of Colleen.

It was thought that the Germans were landing spies, as well as arms and agitators on the West Coast of Ireland.

Carter describes it as an unpleasant area with strong westerly winds and heavy seas, but with a number of places affording good shelter.

They got to know many of the small towns such as Kilrush, at the mouth of the Shannon River where they had good relations with the locals. The bank manager even invited the crew of the ML for Christmas dinner.

Neither he nor his wife was at home, but a sumptuous dinner was laid out, including Irish whisky and stout. Having enjoyed themselves immensely, they left a note of thanks, a large bag of brown sugar (a rare luxury at the time) and a tin of tobacco.

They later learned that the bank manager was the head of the local Sinn Fein and highlights that there was no antipathy towards the Navy by Sinn Fein, just a hatred of the British government.

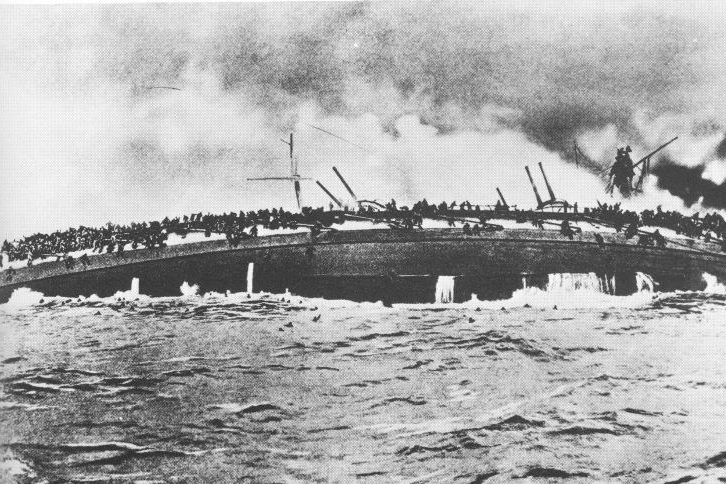

A permanent reminder of New Zealand’s participation in the greatest operation in which the motor launches were involved lies in the cemetery at Dunkirk – the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend in 1918.

Motor Mechanic J.F.H. Batey of the Coastal Motor Boat CMB 33, is buried there, his body having been washed ashore on 17 April 1918 after he had been killed in action on 12 April.

One of the few Motor Launches to actually encounter a submarine was ML 357.

The First Lieutenant of which was Lieutenant J.W. Laurie Stubbs of Auckland, as part of the escort of a convoy between Penzance and Ushant on a misty day in January 1918.

Out of the mist a submarine was sighted at a range of about 70 yards. The ML immediately altered course towards and increased speed to ram the submarine.

A minute or so later this was achieved, the ML passing over the submarine, wiping the propellers and stopping the engines. Lieutenant Stubbs was manning the 3 pounder gun and was able to get one round away at the submarine before it submerged.

ML 357 was in danger of sinking when the submarine re-appeared. Six more rounds were fired, a number of which were believed to have hit, before the submarine either submerged or sank.

The Admiralty considered the submarine to have been either badly damaged or destroyed and the Commanding Officer was awarded the DSC and Lieutenant Stubbs a Mention in Despatches.

More tangibly the crew were rewarded with a bounty of £1,000.

In the Mediterranean the operational patrols and methods were the same as around Britain, only the place names were different, their depot ship being HMS Europa.

Arthur Welch was one of the New Zealanders to serve in the Eastern Mediterranean.

With the cessation of hostilities at the end of 1918, there was a requirement for the occupation of Germany, in which not only the Army, but also the Navy were involved.

One of the naval personnel who took part in this was Lieutenant Charles Palmer, a New Zealander who had joined the Motor Boat Patrol in 1916.

He had spent most of his war in Anti-Submarine trawlers, specifically HMS George Brown, under the command of Lieutenant C.E.S. Farrant RN.

At the Armistice, they were in Dundee before proceeding to Portland to pay off. Lieutenant Farrant was appointed to one of the vessels to go to Germany as part of the Allied occupation force, later to be known as “The Watch on the Rhine”.

Lieutenant Palmer volunteered to join the flotilla proceeding to Germany, although he had already been appointed to command an ML. Instead he transferred to ML 358 as First Lieutenant.

The Flotilla departed England on 21 December en-route to Le Harvre in dead calm seas, 11 MLs in the convoy, escorted by destroyers.

From there the flotilla entered the River Seine at Rouen and commenced the inland journey to Germany.

Proceeding via Paris they entered the River Marne and after negotiating the seemingly innumerable locks (219) and crossing the River Moselle by aqueduct, they eventually arrived at Cologne on 13 February 1919.

![Amokura Training Ship Amokura [formerly HMS Sparrow]](https://navymuseum.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/amokura.jpg)