From the beginning of the war, New Zealand played a key role in naval intelligence and was responsible for the gathering and dissemination of intelligence for the Central Pacific area.

Understanding the importance of intelligence in war, the Senior Naval Officer, New Zealand Division, Captain J.M. Marshall RN, appointed a retired officer in the capacity of Naval Intelligence Officer (NIO) on 4 August 1914.

Commander Robert Newton established a Naval Intelligence Centre, in Wellington, reporting to the Commander in Chief China Station and other centres, such as those at Melbourne, Esquimalt (Canada) and the Cape of Good Hope.

In addition to intelligence he was also responsible for other matters, such as arranging supplies of New Zealand coal for the Admiralty.

The Naval Intelligence Centre was a 24-hour operation, including three watchkeeping officers and a coding section.

It co-ordinated reports on allied shipping arriving/departing New Zealand ports and disseminated information received from overseas.

There were difficulties, for example, at the outbreak of war the NIO did not have access to any cyphers and his only point of contact for classified material was the Governor.

Even if the NIO had been provided with an appropriate cypher he had no means of keeping it secure. Commander Newton left the country in mid-September being replaced by Paymaster W.J.A. Brown, of HMS Torch and he developed the skeleton organisation.

One of the most significant new technologies employed during WWI was radio. This facility was and remains, a two edged advantage, because the enemy can also receive any transmissions.

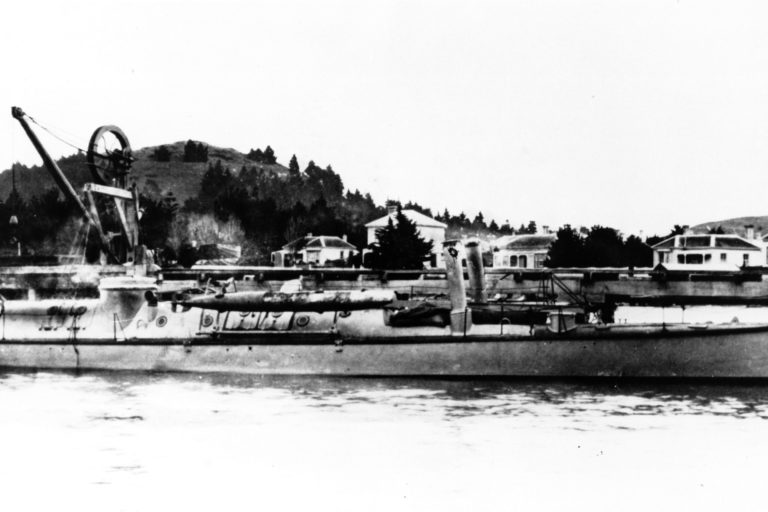

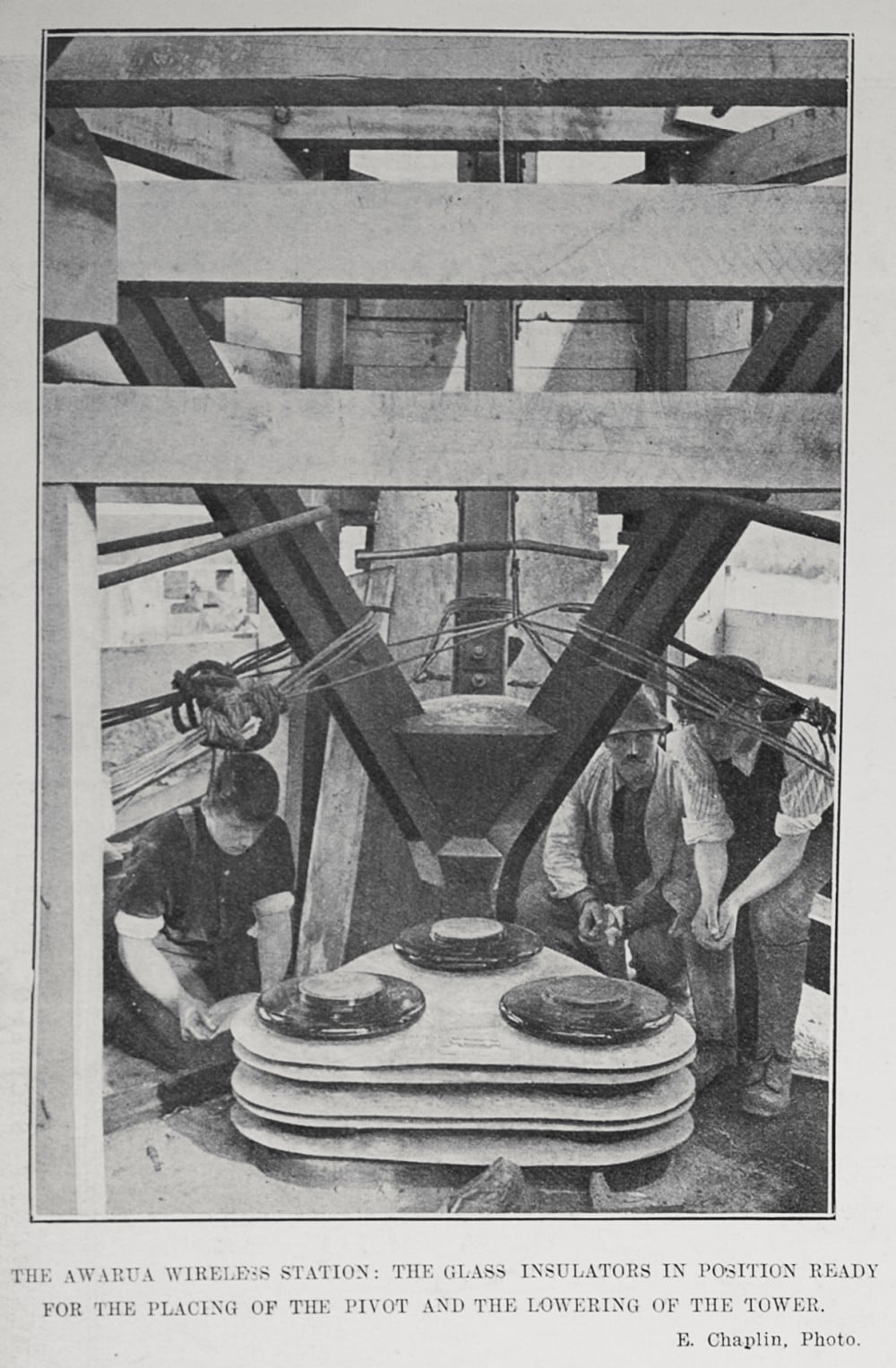

New Zealand had several shore radio stations; at Wellington, Awanui, the Chatham Islands and Awarua, under the control of the Post and Telegraph Department. Following the occupation of Samoa the former German station at Apia also came under New Zealand control.

These were part of a worldwide Empire network, particularly for naval communications.

Even before the war New Zealand stations were making reports of German activity, the first recorded being on 2 August when Awanui reported that the German station at Apia was on the air, working with Nauru.

The Australian stations were also intercepting radio traffic, with Thursday Island reporting German warships working Yap on 4 August.

Two days later the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board were sending reports of the positions and courses of German warships, together with their call-signs.

In early August, the Royal Australian Navy achieved a major coup when it secured the secret codes of a German merchant ship captured off Melbourne.

Intercepted enemy messages were passed between the various authorities and to Navy Office Melbourne, the major intelligence centre of the region.

Even at this early stage the distinctive features of individual radio sets and operators were being exploited.

On 28 September New Zealand was advised how to recognise and distinguish transmissions made by the German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

By October the German codes acquired by Australia were enabling intercepted messages to be deciphered and all intercepted messages were passed to Melbourne as soon as they were received.

New Zealand ships were also involved in intelligence gathering from an early date. On 15 September the SS Marama, off Christmas Island reported hearing German radio signals and call-sign and similarly the SS Talune reported intercepted messages in the Cook Islands area in October.

On 14 October the NIO received a copy of the German HVB code, used between warships and merchant ships, from the Australian Naval Board.

This enabled Paymaster Brown to analyse intercepts and only those that could not be satisfactorily explained were transmitted to Melbourne.

Any intercept indicating the presence of an enemy was given to the Governor and the Chief of General Staff (as Military Intelligence Officer).

Additionally, all British and Allied shipping was warned and telegrams despatched to overseas intelligence centres.

Radio technology was still relatively primitive and there was a great need for assistance from shore stations to facilitate communication, both between ships and between ships and distant shore stations.

In early 1916 the newly established French radio station in Tahiti was requested to become part of the organisation and to report through the British Consul at Papaetee.

While the French were most happy to oblige, there were some severe practical difficulties and the station then communicated directly with the French Consul at Auckland.

At the end of July a suggestion by Paymaster Brown that the Consul should be authorised to pass messages direct to him, in the French language was approved.

This enabled messages to be analysed quickly and any technical explanation to be transmitted through the Consul to the Governor of French Oceania.

The basis for this was that the value of intercepts was entirely dependent upon the time taken for it to be received and scrutinised, and the fact that in its original form the messages were intelligible only to a trained officer.

From October 1914 New Zealand agreed to accept telegrams for allied warships at the British Government rate, rather than the normal commercial rate and from at the beginning of 1916 charges were waived entirely for naval telegrams.

While in essence an organisation for reporting enemy wireless transmissions was in place, serious problems remained.

On 2 May 1916 Paymaster Brown, in his capacity as Acting Senior Naval Officer, wrote to the Chief of General Staff.

He expressed his concern at the fact that the Admiralty were under the misapprehension that the New Zealand stations were keeping a practically continuous naval watch, while in fact the majority of time was occupied in handling other traffic.

If this could not be rectified, the Admiralty should be informed of the true situation.

The Chief of General Staff subsequently issued a memorandum informing all concerned of the need to reduce traffic.

Pursuing the matter, Paymaster Brown wrote to the Secretary of the Post and Telegraph Department seeking information as to the efficiency of the watch possible at each station.

The response was that Awarua could maintain an almost continuous watch; that Awanui seldom handled messages with ships but kept a listening watch for a considerable period; that while more work was done at Apia than Awanui there was still a ‘fair amount’ of time for listening watch and that the station was probably troubled with jamming; that there was not much traffic at Wellington and listening watch for enemy signals was continuous.

However, its reception range was not as great as Awanui or Awarua; and that at the Chatham Islands a close watch was kept for enemy signals on varying wave-lengths during the hours of attendance at the station (not stated).

The location of the station was such that it could read signals over a wide area.

Overall, he stated that good attention was given to listening for enemy signals and that a greater portion of the time was devoted to that, except at Awanui and Apia.

By November 1917 there were six reporting officers in New Zealand and Apia, reporting to the Naval Intelligence Centre in Wellington.

That Centre then forwarded intelligence to the Commanders in Chief China and the Cape of Good Hope, the Navy Offices in Melbourne, Esquimalt, Panama and Callao.

The Naval Adviser was also in direct communication with the Admiralty in respect of the detailed arrangements of the Centre.

In mid-November it was proposed that an intelligence centre be established in Suva, which overlapped the organisation already in place.

After explaining the situation in detail to the Admiralty it was decided that a centre in Suva was unnecessary and that Wellington would retain responsibility for the central Pacific.

Additionally reporting arrangements were redefined: New Zealand, Suva, Fanning Island and Ocean Island were to report directly to the Admiralty and to Wellington, while Tulagi and Vila were to report to the Admiralty and Navy Melbourne.

Radio technology was still relatively primitive and there was a great need for assistance from shore stations to facilitate communication, both between ships and between ships and distant shore stations.

By late 1915, a gap in radio coverage was recognised in the central Pacific which could be filled by New Zealand.

As a cost effective solution, approval was sought from the Admiralty for the operators at the New Zealand stations to be trained in naval procedures, not to full naval standards, but to a level to permit their handling of naval traffic.

Thus the stations became a part of the naval network taking instructions from naval authorities. Besides this significant step other measures had been taken from early in the war.

From October 1914 New Zealand agreed to accept telegrams for allied warships at the British Government rate, rather than the normal commercial rate and from at the beginning of 1916 charges were waived entirely for naval telegrams.

These arrangements developed from scratch continued until the end of the war.