The Maheno and Marama were the poster ships of New Zealand’s First World War effort. Until 1915 these steamers had carried passengers across the Tasman for the Union Steam Ship Company, but as casualties mounted at Gallipoli, the government pressed them into service as hospital ships. With the encouragement of the Governor, Lord Liverpool, a massive public fundraising effort helped ensure the ships were fitted out in good time and to the highest standards.

Officially known as His Majesty’s New Zealand Hospital Ship (HMNZHS) No. 1 and No. 2, these state-of-the-art floating hospitals were crewed by a mixture of civilian seafarers and army medical staff, including nurses. During the Gallipoli Campaign the Maheno carried thousands of wounded soldiers from Anzac Cove to the nearby Greek islands of Lemnos and Imbros. The Marama entered service just after the Allied evacuation from Gallipoli. For the rest of the war apart from a series of frantic dashes across the English Channel during the Battle of the Somme – both ships were tasked with carrying the seriously wounded from the Western Front on the long haul back to New Zealand. By the war’s end these distinctively marked ‘white ships’ had transported 47,000 patients.

Floating Hospitals

Hospital ships had accompanied naval forces since ancient times. Britain had used them most recently during the Crimean and South African wars. The Hague Convention of 1907 laid down the rules. It required hospital ships:

- to be clearly marked with white hulls, green stripes and red crosses

- help the injured and sick regardless of nationality

- not be used for any military purpose

- not interfere with or hamper combatants

- be available for inspection and verification.

New Zealand took those rules very seriously during the First World War. Its ships carried no weapons at all and even side arms brought aboard by wounded officers were put ashore at the first port of call. There were three types of vessels. Hospital ships were full conversions. Hospital carriers were quick, limited conversions, although they, too, had to stick to the rules. Ambulance transports (nicknamed ‘black ships’) could carry troops and cargo but were not distinctively marked and were therefore fair game. New Zealand’s two ships, Maheno and Marama, were full hospital ships.

Civilian Days

The ships were owned by the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand Ltd, the country’s biggest private business. Run from Dunedin since 1875, it was also the southern hemisphere’s largest shipping line, able to draw on a mixture of New Zealand, Australian and British capital. The Union Company had a history of innovation. In the early 1900s, its founder, James Mills, took a shine to the new-fangled marine steam turbine, a fuel and labour-saving engine that also made life easier for passengers by running more smoothly and quietly than reciprocating engines. In 1904 Union commissioned the Bass Strait ferry Loongana, the world’s first seagoing turbine merchant ship. Even before that ship proved its worth, Mills ordered his next trans-Tasman liner as a turbine. He gave the job to Scottish shipbuilder William Denny & Bros, a founding shareholder that had built every new Union Company ship since 1875. This became the Maheno of 1905. It was no North Atlantic liner, even smaller than a modern Cook Strait ferry, but the company’s first (and only) two-funnel Tasman liner shaved a full day off the usual five-day crossing.

The stylish Maheno captured public attention, but was not perfect. The ship chewed through coal, had clumsily designed furnace doors and ‘rolled on wet grass’ as seafarers used to say. Canny firemen and trimmers took jobs on other ships if they could get them. In 1914 the company spent a fortune on completely re-engineering the ship at Port Chalmers. The Maheno’s shortcomings were the last straw for the company, which had complained about several recent Denny ships. In 1906 it gave the contract for its next passenger liner to another Scottish builder, Caird & Co of Greenock. The Marama of 1907 reverted to conventional reciprocating steam engines and a single funnel.

Technical details: TSS Maheno

Builder: William Denny & Bros, Dumbarton, Scotland

Tonnage: 5323 gross

Dimensions: 121.9 m long, 15.2 m wide, 6.95 m draft

Top speed: 17 knots

Passengers: 231 first class, 120 second class and 67 third class

Crew: 113

Technical details: SS Marama

Builder: Caird & Co, Greenock, Scotland

Tonnage: 6437 gross

Dimensions: 128 m long, 16.1 m beam and 6.9 m draft

Top speed: 16 knots

Passengers: 270 first class, 120 saloon and 100 (200 max) fore-cabin passengers

Crew: 140

Lord Liverpool’s Campaign

Hospital Ship Souvenir Programme

Gallipoli was a bloody mess. Within hours of their landing on the Turkish peninsula on 25 April 1915, New Zealand soldiers were falling in distressing numbers. The carnage staggered politicians and the public, none more so than the Governor, Lord Liverpool. After the government ordered a hospital ship, Liverpool made it his pet project and suggested running a public appeal to equip the vessel with medical equipment and patient comforts. The government would pay the charter fees, fund the structural cost of building the operating theatres and wards, and then meet the ship’s operating costs (fuel, wages, port fees etc.). “I have not been allowed to go on active service, but in this way I will be able to do my little bit” he stated at the time.

Although Cabinet had originally planned to pay for everything, Liverpool’s suggestion inspired the public and gave Kiwis too young, old or infirm to fight the chance to ‘do their little bit’. Working with the mayors of the four main centres and with Red Cross and St John, Liverpool appealed for goods or cash. His Excellency’s list included bedding, bandages, shoes, slippers and clothing as well as comforts such as deck chairs.

Hospital Ship Fund

Most New Zealanders responded enthusiastically. All around the country people organised fundraising sports events and concerts. Children ran penny drives, Red Cross workers trimmed bandages and others donated books and clothing. One Christchurch man ‘auctioned’ a minute’s ownership of his race horse. Some businesses gave in kind. Southern cereal miller Fleming & Co donated supplies of ‘Cremoata’. A Christchurch furniture factory gave the materials for 100 deck chairs and its workers gave up their day off to assemble them. By August 1915 the Hospital Ship Fund had brought in £47,000 – equivalent to over $6.5 million today.

The big-ticket gifts were two motor launches for each ship, needed to transport patients and crew to and from shore in anchorages that lacked wharves. They would prove their worth off Anzac Cove and also in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where the ships often had to anchor in the stream. In Auckland the NZ Power Boat Association paid £350 (over $50,000 today) for a launch nearing completion. Gisborne district residents paid an Auckland boat builder a similar amount to construct a new launch for the Marama.

Building a Floating Hospital

Even though several Union Company ships were serving as troopships and transports, the line’s fleet was still big enough to supply a hospital ship. In May 1915 it sent the Maheno to its Port Chalmers dockyard for conversion along the lines set out by War Office (UK) plans. Hair mattresses, feather pillows, clean sheets – what more can the heart of man desire! – Kai Tiaki

Transforming the Marama

Fortunately the company had the shipwrights to turn the ship around quickly and Dunedin’s manufacturers knew how to build hospital equipment. In just a month they removed and stored the Maheno’s luxury fittings, gutted many cabins and public spaces, and built operating theatres, X-ray rooms and specialist labs. One of the bigger jobs was fitting two electric lifts large enough to transport two patients in stretchers, two in cots (beds) and their caregivers between decks as required. The Maheno could take 340 cot cases and the Marama 592, although on occasions the ships had many more aboard. People were just as important as fittings and equipment. Although the government paid everyone’s wages, the Union Company provided the crew and did most of the practical work needed to operate the ship through unfamiliar ports around the world. The army provided everyone else, who were called the ship’s ‘personnel’ (the Union Company men were ‘crew’). Medical orderlies made up the bulk of the personnel. The rest were officers, the surgeons and physicians, army chaplains and the nurses, the only women aboard hospital ships. The personnel often referred to themselves by the name of their ship, either ‘Mahenos’ or ‘Maramas’. Finally, in July 1915, it was time to sail for Gallipoli.

The hospital ships followed a standard route, coaling at an Australian port (usually Albany) and Colombo in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on their way to the Suez Canal. By the time they reached Western Australia, all but a handful had stopped ‘feeding the fishes’ (being sea sick) and gained their sea legs. A few nurses and orderlies never got the hang of the sea and had to be transferred to shore establishments. By the time the ship reached the Mediterranean, even the most land-lubberly nurse or orderly had settled into the daily routine and knew what to do when officers gave the signal for fire or lifeboat drill.

The Maheno Goes to War

The Maheno arrived in the Mediterranean in time for the Allies’ bloody late-August 1915 offensives. Not much had improved since the April landings on the peninsula. The troops ashore were short of water, nutritious food, medical facilities and shelter. At times disease was as much a threat as bullets and shells. Even at the best of times, flies, lice, stress and an inadequate diet compromised a man’s health even before he copped a bullet or shell fragment.

That was just the beginning of fresh horrors because, unlike on the Western Front, there were no safe rear areas for casualty evacuation and initial treatment. The Ottoman (Turkish) troops commanded the high ground, able to fire on the landing beaches and offshore anchorages. Maheno’s crew and personnel compared the trenches and shelters dug into the lower cliffs to rabbit burrows, soon learning that most of these offered only limited protection. Although Turkish gunners respected the Allied hospital ships, operating off Anzac Cove was fraught with difficulties. On the Western Front hospital ships docked far from the battle front alongside modern wharves. Under these safe, secure conditions it was easy to transfer patients from trains or ambulances. At Anzac, in contrast, the Maheno had to anchor in the open sea and load patients from launches, trawlers and even towed barges. Unless marked clearly with Red Crosses, these small craft were legitimate targets. Even when the shells were falling far away, it was slow, laborious work, easily disrupted by bad weather.

Transferring Gallipoli Wounded to Maheno

When the small craft came alongside the Maheno, the crew and personnel used the ship’s derricks to winch up patients and their caregivers (though the ship’s unusual side doors made this easier under the right sea conditions). Once aboard, medics quickly assessed the men. On those hectic, bloody days of late August 1915 ‘walkers’ (as they called the lightly injured), were likely to be sent to the other side of the Maheno to be transported by trawler or launch to a humble transport or freighter. On these ‘black boats’, medical care might be left to a veterinarian and a couple of orderlies, but there were too many seriously hurt men to provide full service care for everyone. On the Maheno’s first day, 400 ‘walkers’ were offloaded just to allow the overcrowded ship to dash to the nearby islands of Imbros and Lemnos to deposit the most seriously wounded in the makeshift hospitals there.

The Anzac Shuttle

And so began an exhausting period of shuttling between the Greek islands and Anzac. Once off the beach, everyone on board ‘turned to’ whenever the bugler played the sick parade call, even the Union Company seafarers, technically not part of the medical establishment.

The Marquette Tragedy

32 New Zealanders, including ten nurses, died when the troopship Marquette was sunk by a German submarine in the Aegean Sea on 23 October 1915. If the medical staff had been on a marked hospital ship they would almost certainly not have been targeted. Tired firemen and trimmers helped army orderlies and nurses comfort and move patients and serve food and tea. Third Officer John Duder bolted from his first stint in an operating theatre, but came back for more later. ‘Some of the operations are awful’, he confided in his diary. The short shuttle journey to Imbros and Lemnos was no leisure cruise. At night the ships’ officers had to keep a sharp lookout for blacked-out warships and transports. In daylight they stopped for sea burials. Duder wrote emotionally about having to lower a boat to sink some shrouded bodies that had failed to disappear. ‘I came back & was ill at the thought of it’. The return journey to Anzac was only marginally better. While there were no patients to worry about, the nurses and orderlies kept busy fumigating the wards and theatres, remaking the cots and rolling bandages while the seafarers scrubbed the decks. They had to scrub hard, because many patients had arrived in a filthy condition.

‘A floating palace’

The Maheno took patients from several nations, but there is no doubt that its familiar profile gladdened many Kiwi hearts. ‘The Maheno is a floating palace’, Cecil Malthus wrote from the beaches. Looking out over the bay, Chaplain William Grant thought that the Union Company workhorse looked like poet Coleridge’s ‘painted ship upon a painted ocean.’ One soldier, a former Union Company officer, masqueraded as a walking wounded just to enjoy a bath, food, cigar and a chat with the captain for a few precious hours before returning to battle. The food worked wonders. Although the ship’s meat and poultry were usually tinned or frozen, they were a delight to men accustomed to tinned bully beef, dried biscuits and a much-loathed jam usually enjoyed more by the summer flies than by the men. Even something as simple as fresh-baked bread and New Zealand butter worked wonders. ‘How they go for it’, a Union Company officer remarked as he helped the army personnel butter bread while they lay off Anzac Cove. ‘The first remark is always about the butter and how good it tastes.’

Hierarchies

What was life like aboard a First World War hospital ship? That largely depended on your job, your rank and your gender. In peacetime the ships had catered to three classes of passengers, their ticket prices set accordingly. No one bought tickets for a berth on a hospital ship, but the military’s ancient division between officers and ‘other ranks’ imposed its own set of rules and restrictions. The medical establishment changed over time, but on the Maheno there were typically seven to eight doctors, three chaplains, fourteen nurses and 60-70 orderlies. The doctors, chaplains and nurses had officer status and enjoyed better accommodation and first class passenger menus. Or they should have. Although the government had said that nurses would be treated as officers, Lieutenant-Colonel James Elliott, the senior military officer on the Maheno’s first voyage, withdrew many of their privileges, greatly souring relations. The ships were small and crowded, but some women felt short-changed in the amount of open deck areas allocated to them, mixing between men and women being restricted to certain times and places. Even so, the other personnel would have envied the nurses’ treatment. Orderlies, masseurs and technicians made up the vast bulk of the ships’ musters, although their ranks also included food service workers and clerical staff.

Although peacetime passengers were used to sharing four or eight-berth cabins with strangers of the same sex at peak season, the army personnel were crowded together and dined according to peacetime third-class standards. The army never got the orderlies’ accommodation on the Maheno quite right, a problem for the men who performed some of the most physically taxing duties on the ship. The crew occupied their peacetime quarters, Union Company cooks and stewards serving the ship’s officers first-class food and everyone else a third-class menu. Crew numbers were down about 10% on peacetime, since army personnel catered for their own personnel and patients. The crew was divided into the deck department (officers and seamen), the engineering department (engineers, firemen and coal trimmers) and what would now be called the catering or hotel department (cooks, stewards, laundry workers etc.).

On the Maheno’s first voyage the men ranged in age from the 56-year-old master to a sixteen year old brass boy. Many had been born overseas, most in the UK, but some came from Australia, the United States, Scandinavia and even Russia. Since Dunedin was the ship’s home port, Otago men featured strongly on the crew lists of both ships. Crew accommodation was adequate by the standard of the day, although in the hot Mediterranean the firemen’s unventilated area was considered bad, especially on the Maheno. On both ships, the hardworking ‘black gang’ – the firemen and trimmers – were always the men most likely to delay the ships by being late or by coming back drunk. Serving on a hospital ship was not always good for your health, even if you were a medic. During the Marama’s first commission over 60% of the orderlies fell sick, as did 40% of the nurses and all but one doctor. The crewmen also fell victim to the usual accidents created by moving machinery and handling derricks and mooring ropes.

Patients also dined and were accommodated according to rank, with officers enjoying more spacious wards. While surgery was important during the Gallipoli and the Somme phases of the ships’ careers, on the long voyages back to New Zealand, rest, good food and rehabilitation worked most of the shipboard miracles. The water in the ships’ baths may have been salt, not fresh, but clean sheets, daily bathing and a balanced diet turned many cot cases into ‘walkers’ long before they re-entered New Zealand waters. Entertainment varied. In fine weather, patients enjoyed a book or a smoke in their deck chairs (although smoking was banned in some areas, cigarettes were dished out in patient comfort packs). Quoits tournaments and boxing matches were popular with spectators and participants alike. The chaplains helped with lectures and library duties. Music and concerts were popular, as was sightseeing at ports of call. For many personnel and patients, this was their first ‘OE’ and Colombo their first taste of the exotic east. In Egypt people talked about going ‘Sphinxing’. Not everyone behaved well, with patients sometimes overstaying their leave. Comments about dark-skinned races were sometimes blunt.

The Maheno’s voyage to Gallipoli was not as smooth as Governor Liverpool liked to portray. Lieutenant-Colonel Elliott, the officer commanding (as the senior army doctor was known), got off to a bad start by denying the nurses some of the privileges due to personnel with officer status. More disturbingly, he tried to boss the ship’s master, Captain McLean. The well-known maritime phrase ‘master under God’ seems to have been a mystery to him. In August 1915 Elliott stunned Defence Department officials in Wellington by telegramming ‘am I in supreme command and the ships master responsible to me for the safe navigation and discipline or is the master in supreme command?’ The issue made it into the press and briefly involved the attention of New Zealand’s high commissioner to London. Elliott was told firmly that while the ship’s master should consult him, the captain had the final say. The Otago Daily Times commented “rumours persist that the vessel did not carry a strikingly happy family.”

A more serious incident occurred off Malta in September 1915. The Maheno’s 1914 re-engineering had only slightly improved the working conditions of the ‘black gang’, the firemen and trimmers who fed the ship’s ravenous and awkwardly designed boilers. If it could get hot and hellish on the Tasman, imagine what it must have been like in the heat of the Mediterranean. The engine room was short-staffed, so the men went on strike – or mutinied in wartime terms. Captain McLean brought the ship back to port where he had 26 men arrested and replaced by Maltese workers. Lord Liverpool also caused a few problems. He often interfered in the details of his pet project and right at the beginning he complicated staffing problems by announcing that the ships’ medics could serve no more than six months if they wished. Some doctors feared having their practices’ patients poached by others if they were away from home too long, so the high turnover at voyage-end increased the training needed for the next one.

After Gallipoli

New Zealand’s second hospital ship, the Marama, missed Gallipoli, reaching the Mediterranean a few weeks after the Allies abandoned the peninsula. The two ships’ service pattern would now be dominated by long voyages back to New Zealand to discharge wounded Kiwis and to refit at Port Chalmers. At first some government ministers questioned why such expensively equipped ships should act as glorified troop transports, but it made sense to the hard-pressed British. By 1916 the war on the Western Front had become a numbers game as the Allies waged a war of attrition against Germany and Austria-Hungary. Before planning a new ‘push’, the army always cleared out the base hospitals and convalescent centres in Britain and Egypt, knowing that their beds would soon be in high demand. Lightly wounded men who might expect to serve again shortly stayed put, but those deemed too sick or injured to make a speedy return to full health were put on hospital ships and sent back to Australia and New Zealand. There they could recover and the more able-bodied among them could find other ways of contributing to the war effort.

The Battle of the Somme

The main exception to the hospital ships’ post-Gallipoli voyage pattern came in July 1916 when Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig launched the massive Somme offensive. On the first day alone, nearly 60,000 British officers and men were killed, captured or wounded. Coincidentally, the Marama was lying at Southampton and the Maheno was due there in two days’ time. It was the hospital ships’ greatest challenge. Many Marama crew and personnel were ashore, on leave or were conducting ship’s business in places as far away as London when news broke. Telegrams flew forth to summon them back, but inevitably some could not be reached, so the Marama sailed shorthanded, warned that it might soon have to squeeze in 1000 patients, 400 more than it was equipped to handle. Corporal John Garland recorded “There are no soft jobs going about this boat now. Sometimes we don’t get any sleep for 48 hours…if this keeps up we will all be knocked out: it’s too much.”

It was hell. Doctors, nurses, orderlies and seafarers struggled to deal with the numbers. Not only were the injuries often horrific, the men had come straight from the trenches, instead of having passed through behind-the-lines treatment centres. That meant that they were muddy, bloody and often crawling with vermin, some of which transferred themselves to the ships’ personnel; ‘Dhobi itch’, the medics called it. ‘The stench arising from the various wounds in a crowded ward can be better imagined than described’, the official account of the Marama’s service noted. Everyone got a tetanus jab because the heavily manured Western Front fields were full of the deadly bacillus.

Patients Crossing English Channel on the Marama

Mines lurked everywhere in the English Channel and the huge 8-metre tidal range at Le Havre sometimes made it very difficult to position gangways. Everyone not needed to navigate the ship helped with tending the wounded and with the catering. The Marama’s stewards stopped serving patients at mess tables and simply handed out cutlery and food, telling patients to eat ‘in much the same manner as children are served at a school picnic’. The ships were crowded for the short cross-channel dash. On one memorable occasion the Marama struggled to find room for nearly 1600 patients. The Maheno, refitted to carry 600 patients, picked up 1141 on its first trip. “Many badly wounded men had to made do with deck chairs rather than cots. They could sleep in any position, given a blanket and a sitting room, and it was all many of them wanted. Some would sleep back to back” Lord Liverpool. For weeks the ships criss-crossed the Channel, sometimes meeting up in the same port, sometimes passing each other at sea. When passing mid-channel the crews and patients would cheer each other loudly.

During the battles for the Somme, the Maheno carried 14,631 patients on fourteen voyages and the Marama conveyed 10,978 in eleven journeys. These tallies included 973 German prisoners of war, some of whom looked very scared, having been told by their own propaganda that U-boats and mines had made the English Channel impassable.

The ships resumed their trans-hemispheric voyages in September/October 1916 as the Somme battles fizzled out. The long voyages took them away from the hazardous North Sea and Mediterranean zones for most of their journeys, but in early 1917 Germany, being strangled slowly by the Royal Navy’s blockade of its sea trade, hit back. In February it declared unrestricted submarine warfare, closing off all but a few narrow routes around the British Isles to all shipping. Soon hospital ships were coming under attack in what the Allies referred to a ‘war on hospital ships’. While some attacks may have been mistakes, others clearly were not. In May 1917 the War Office ordered all nursing sisters off imperial hospital ships, to the deep disappointment of the women. The ban was lifted a few months later when Germany allowed neutral Spanish commissioners to supervise hospital ships’ passage through narrow transit routes.

Post-war fates

The end of the war saw the Maheno and Marama working as troopships, helping other units of the Union Company fleet to carry New Zealanders back home. By the time they returned to peacetime duties in 1919, they had carried over 47,000 patients and prisoners of war. The ships returned to Port Chalmers to offload their hospital fittings – (the Maheno’s went to South Island hospitals and the Marama’s to North Island ones). Reequipped with their peacetime finery, they resumed their old runs, the Maheno principally on the Tasman and the Marama mainly on the trans-Pacific service.

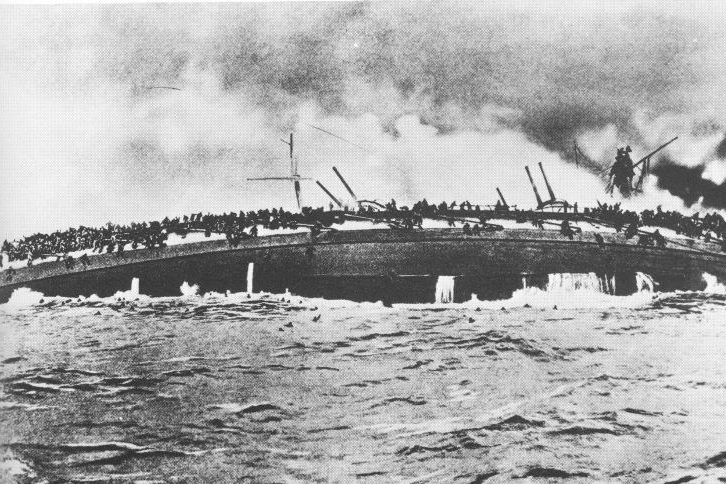

The Maheno Washed Up on Fraser Island

Age and the Great Depression finally caught up with both ships in the early 1930s. The Maheno had been idle for almost four years when the Union Company sold it for scrap in 1935. The ship left Sydney towed by an even older steamer, also bound for the same Japanese breaker’s yard. The Maheno never got there. The towline parted in mountainous seas off the Queensland coast. Authorities feared the worst, but days later searchers found the ship and its small tow crew hard aground on Ocean Beach, Fraser Island. The Japanese insisted that they could salvage the wreck. For months three owners’ representatives camped on the beach defending their so-called ‘asset’. A couple even got married aboard the listing hulk as the sands built up around it.

The Maheno Wreck

Eventually the Japanese saw sense and abandoned the wreck, which became a tourist attraction. More recently, a bunch of British sightseers liked it so much that they named their alternative rock band The Maheno Wreck. The Marama had a brief respite but went for scrap in 1937.

Legacies

So what is the hospital ships’ legacy? Museums display some of their ships’ bells and Auckland’s Voyager National Maritime Museum is restoring the Nautilus, one of the Marama’s launches. Their biggest tribute sits four-square in the registry complex at Otago University. In 1919 authorities gave the medical school the surplus money to build a gymnasium and drill hall for its training corps. But the cadet unit had disbanded by the time the governor-general opened Edmund Anscombe’s handsome two-storey building in 1923. Maheno and Marama Hall (later shortened to Marama Hall) has been the campus’s centre for music for many years.