The treatment and transfer of severely wounded from the battle site to somewhere they can be properly treated often requires transport by sea.

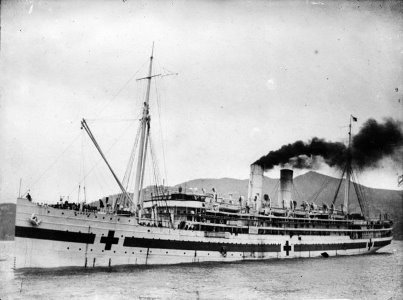

This was done in hospital ships and during the First World War New Zealand provided two of these vessels, funded by a combination of Government finance and voluntary donations.

They were the brainchild of the Governor, Lord Liverpool, who played a major part in their inception and took a personal interest in both ships.

Following the landings at Gallipoli and receipt of the casualty lists, the Governor, Lord Liverpool, suggested that New Zealand should provide a fully equipped hospital ship, a suggestion that was immediately accepted by the British Government.

With much optimism it was anticipated that the ship would be ready to leave New Zealand within a month.

To fit-out and equip the ship a plea for public donations was launched, with the Bank of New Zealand accepting donations and the Order of St John accepting donations in kind.

General details of the fitting-out requirements of the ship were forwarded from Britain, including the painting of the ship white with a green band and red crosses.

Subsequent correspondence advised that the ship should wear the Red Cross Flag and the New Zealand Blue Ensign and that two chaplains should be carried. In the event three chaplains were borne.

The SS Maheno was chartered, fitted-out and maintained by the New Zealand Government while the equipment was funded by the Governor’s appeal.

There were eight wards and two operating theatres, together with other essential equipment, such as a sterilising room, X-ray room and laboratory

The work was personally superintended by the Governor and en route to the ship the equipment was ‘warehoused’ in the ball room at Government House.

Also on board were two motor launches which had been donated, one from Auckland and the other from Wellington. From comments received the ship was better fitted out than any of the other Allied Hospital Ships.

The original date for the ship’s departure was seen to be too optimistic and was put back to 10 July.

At this stage the intention was for the ship to complete one voyage, of about six months duration, returning to New Zealand with soldiers incapable of further service.

Although the ship would generally come under the jurisdiction of the War Office the Government was explicit that the ship and its personnel belonged to New Zealand, in particular, no personnel or equipment were to be removed from the ship.

As early as 26 July, the possibility of a second voyage was being considered, and by the end of the month it was being assumed.

At 12.55 pm on 11 July, following a Church parade, Maheno sailed from Wellington. She was under the command of Captain D. McLean with 105 officers and ratings and Colonel W.E. Collins in charge of 81 officers and other ranks of the New Zealand Army Medical Corps, including 14 nurses.

Additionally, there were some naval signalmen included in the complement. Also embarked were 68 nurses enroute to Egypt.

Each member of the medical staff had received a distinctive green and scarlet lanyard from the Governor.

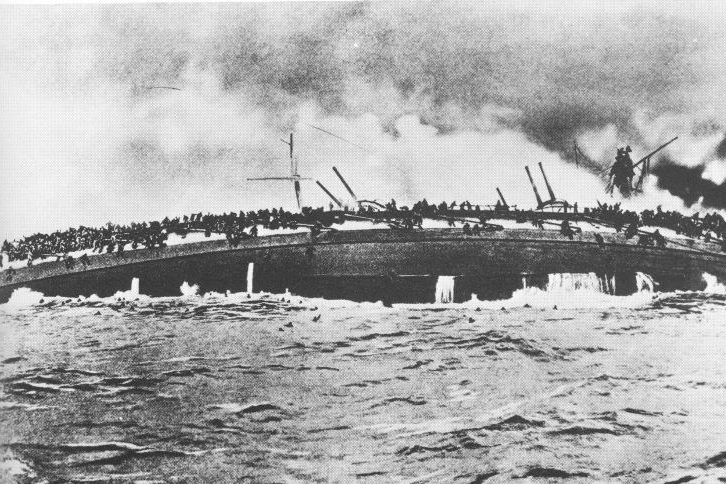

Maheno arrived at Suez on 16 August and on the 25thanchored in ANZAC Cove, with the odd stray bullet landing on the deck.

The next afternoon a battle was fought ashore and with the first load of 445 wounded Maheno went to Mudros on the 28th, to transfer them to a hospital carrier the next day.

Having cleaned the ship it returned to ANZAC Cove.

The next five weeks were spent treating wounded from Gallipoli, either at ANZAC Cove, Mudros or transporting them to Malta or Alexandria.

On 8 October, at Alexandria, the ship received orders to proceed to England. With a full load the ship sailed at 10 pm, arriving at Southampton at 9.55 am on 17 October, after a rough passage across the Bay of Biscay.

Maheno left Southampton on 30 October, returning to the Mediterranean and ANZAC Cove. With 418 patients Maheno then sailed for Alexandria, arriving on 15th November.

A week later orders were received to proceed to New Zealand and with 76 patients the ship sailed on the 22nd embarking further patients at Port Said and Suez.

After an uneventful voyage Maheno arrived at Auckland on 1 January 1916.

At Auckland the ship was met by the Governor and a civic reception was given to the personnel. Sailing that evening Maheno arrived to another civic reception at Wellington, before sailing for Lyttelton and Port Chalmers with the Governor on board.

Before arriving in Dunedin one of the Royal Navy signalmen, Signalman Pattie, received a presentation for rescuing a man who had fallen overboard.

The patients were given a civic welcome at Dunedin.

Two months after Maheno left New Zealand Lord Liverpool was already considering the possibility of New Zealand providing a second hospital ship and this too was immediately accepted.

The second ship was the SS Marama, and at 6,437 tons, larger than Maheno, able to carry 508 wounded in cots and it was anticipated that it would arrive in Egypt about the end of December 1915.

Again the Governor was responsible for equipping the ship. Fitting out took until 30 November, when it proceeded to Wellington to embark the medical personnel, sailing on 5 December.

Like Maheno, Marama was intended primarily to carry wounded New Zealanders, although it was placed at the disposal of the War Office and could carry men of the Imperial forces when possible.

With this object it was proposed that the ship first proceed to Gallipoli. Again there was a strict condition imposed that none of the medical officers, nurses or attendants were to be removed from the ship.

Marama arrived at Port Said on 18 December, where wounded were embarked for Alexandria.

With a further load of wounded embarked Marama sailed for Southampton, arriving on 31 January. There the ship was inspected by the Admiralty and further improvements taken in hand to bring it up to a first class standard.

Marama sailed for Alexandria on 15 February with Australian and New Zealand wounded for onward repatriation.

Maheno sailed from New Zealand on its second charter in early 1916 and by July both ships were working on the cross Channel run, between France and England as there were insufficient cases requiring return to New Zealand to fill either ship.

In September the situation changed, with the New Zealand Division being heavily involved in the Battle of the Somme.

For the Hospital Ships this resulted in much activity on the cross Channel run, and by the middle of the month there were sufficient cot cases to fill Marama for return to New Zealand. By the end of October there was also a full load for Maheno.

Marama’s return was not without some controversy, with Navy Office Melbourne advising New Zealand that it intended to load 15 tons of cordite in the ship for transit to New Zealand.

As could be expected this resulted in protests from both the Governor of New Zealand to the Governor General of Australia and the Acting Senior Naval Officer to the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board.

The proposal was cancelled. Just who and what could be carried in hospital ships was to be an on-going consideration.

The situation was re-iterated by the Secretary of State for the Colonies in September 1917 and in November of that year it was further advised that even the carriage of swords and revolvers of wounded officers was prohibited.

It had originally been intended to route Maheno via South Africa, however the ship could not carry sufficient coal for the passage from Durban to Fremantle and accordingly the ship was routed through the Suez Canal.

This caused some anxiety in New Zealand because of the mining of a Hospital Ship in the Mediterranean earlier in the year.

In response the Secretary of State for the Colonies advised that while the Admiralty could not guarantee that Maheno would not strike a mine, every possible means would be taken to avoid this happening.

Throughout there was a continual fear that one of the ships could be lost through enemy action.

This engendered numerous telegrams from the Governor to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, which if a response was received, was to the effect that all possible efforts were being made to ensure the safety of the ships.

One result was that they were not used in the Mediterranean from 1916. During mid-1918 the danger to hospital ships around England was such that none were permitted to go to, or sail from the United Kingdom.

This resulted in the two New Zealand ships being employed conveying wounded from either Marseilles or Suez to New Zealand.

The end of the war did not see the service of the hospital ships cease, rather the workload increased. Not only was there a need to transport invalids from England to New Zealand, but there were many to be taken from the Middle East to Britain.

In January 1919 the British Ministry of Shipping wished to take over the Charter of Marama and hoped that the ship would be transferred with all fittings intact.

The Governor General responded that while all of the voluntary equipment would willingly be handed over, it was hoped that the instruments, X-ray machine and bacteriological equipment could be retained as it could not be purchased in New Zealand and it was intended to allocate it to New Zealand hospitals.

After some discussion as to the actual terms this was agreed and subsequently similar arrangements were made in respect of Maheno.

When their service under the Imperial Government was completed the ships returned to New Zealand to be refitted and returned to their owners.